PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

India's Crony Capitalism: Modi's Pal Adani's Wealth Grows at the Expense of Ordinary Bangladeshis and Indians

Prime Minister Shaikh Hasina has agreed to buy expensive electricity from India in spite of a power glut in Bangladesh, according to a report in the Washington Post. The newspaper quotes B.D. Rahmatullah, a former director general of Bangladesh’s power regulator, as saying, "Hasina cannot afford to anger India, even if the deal appears unfavorable." “She knows what is bad and what is good,” he said. “But she knows, ‘If I satisfy (Gautam) Adani, Modi will be happy.’ Bangladesh now is not even a state of India. It is below that.” The Washington Post report says: "Facing a looming power glut, Bangladesh in 2021 canceled 10 out of 18 planned coal power projects. Mohammad Hossain, a senior power official, told reporters that there was “concern globally” about coal and that renewables were cheaper".

|

| Gautam Adani (L) and Narendra Modi |

|

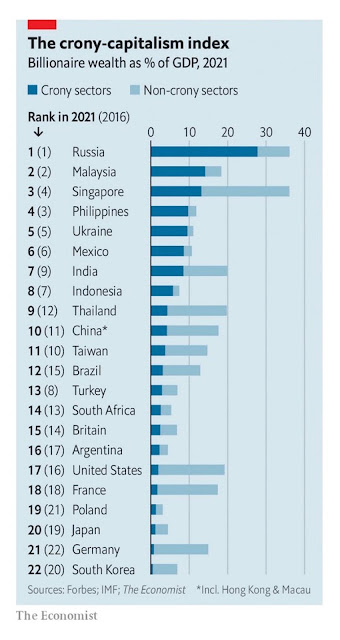

| India Ranks High on Crony Capitalism Index. Source: Economist |

Hasina recently visited New Delhi to seek political and economic assistance from the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. This summit was preceded by Bangladesh Foreign Minister Abdul Momen's trip to India where he said, "I've requested Modi government to do whatever is necessary to sustain Sheikh Hasina's government". Upon her return from India, Sheikh Hasina told the news media in Dhaka, "They (India) have shown much sincerity and I have not returned empty handed". It has long been an open secret that Indian intelligence agency RAW helped install Shaikh Hasina as Prime Minister of Bangladesh, and her Awami League party rely on New Delhi's support to stay in power. Bangladesh Foreign Minister Abdul Momen has described India-Bangladesh as one between husband and wife. In an interview with Indian newspaper 'Ajkal,' he said, "Relation between the both countries is very cordial. It's much like the relationship between husband and wife. Though some differences often arise, these are resolved quickly." Both Bangladeshi and Indian officials have reportedly said that Sheikh Hasina "has built a house of cards".

|

| Shaikh Hasina (L) with Narendra Modi |

The Washington Post reports that the Modi government has changed laws to help Adani’s coal-related businesses and save him at least $1 billion. After a senior Indian official opposed supplying coal at a discount to Adani and other business tycoons, he was removed from his job by the Modi administration, according to the paper. Modi has continued to support Adani's business with discounted coal even after telling the United Nations he would tax coal and ramp up renewable energy. India is the world's third largest carbon emitter.

|

| World's Top 5 Carbon Emitters. Source: Our World in Data |

While the coal prices have declined to the level before the start of the Ukraine War, Adani’s power would still cost Bangladesh 33% more per kilowatt-hour than the publicly disclosed cost of running Bangladesh’s domestic coal-fired plant, according to Tim Buckley, a Sydney-based energy finance analyst.

|

| India's Crony Capitalism: Adani Enterprises Stock Up 56,000% on Modi's Watch |

Gautam Adani has become India's richest and the world's second richest person (after Elon Musk) since the election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014. Financial Times calls Adani "Modi's Rockefeller". Adani's rise owes itself to India's crony capitalism, according to France's Le Monde. Here's an excerpt of a Le Monde story on Adani:

"Adani has not invented some revolutionary technology or disruptive business model. His meteoric success cannot be attributed to innovation. In each sphere of activity among his conglomerates – airports, ports, mining, aerospace, defense industry – the Indian state plays a significant role, whether in allocating licenses or signing contracts. He is known as a close friend of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who also hails from Gujarat, a state in western India".

Adani has lent his personal airplanes to Modi for BJP's election campaigns. Adani has also recently taken over NDTV, the only Indian major TV channel known for its independence from the BJP government. This takeover has forced Prannoy and Radhika Roythe, the channel's founding couple, to step down. It has also forced out Ravish Kumar, a harsh critic of the Modi regime who hosted a number of popular shows like Hum Log, Ravish ki Report, Des Ki Baat, and Prime Time.

|

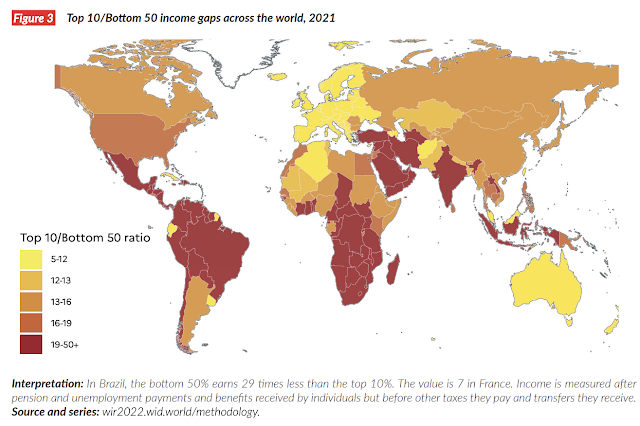

| Income Inequality Map. Source: World Inequality Report 2022 |

India is one of the most unequal countries in the world, according to the World Inequality Report 2022. There is rising poverty and hunger. Nearly 230 million middle class Indians have slipped below the poverty line, constituting a 15 to 20% increase in poverty. India ranks 94th among 107 nations ranked by World Hunger Index in 2020. Other South Asians have fared better: Pakistan (88), Nepal (73), Bangladesh (75), Sri Lanka (64) and Myanmar (78) – and only Afghanistan has fared worse at 99th place. Meanwhile, the wealth of Indian billionaires jumped by 35% during the pandemic.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

India Among World's Most Unequal Countries

Shaikh Hasina Seeks Modi's Help to Survive

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

Indian Economy Grew Just 0.2% Annually in Last Two Years

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

India: World's Biggest Oligarchy?

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid19 Crisis

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Counterparts

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan's Sehat Card Health Insurance Program

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

COVID Lockdown Decimates India's Middle Class

COP27: Pakistan Demands "Loss and Damage" Compensation

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

How Has India Built Large Forex Reserves Despite Perennial Trade Deficits

India's Unemployment and Hunger Crises"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

Riaz Haq

Modi’s Vision for India Rests On Six Giant Companies

https://www.wsj.com/articles/modi-india-economy-reliance-industries...

Conglomerates are executing projects with a scale and speed that have eluded India in the past. ‘Era of great concentration.’

Prime Minister Narendra Modi says this is India’s decade. That claim rests heavily on a handful of dominant conglomerates.

Increasingly aligned with Modi’s priorities, the roughly half-dozen mega-firms—which include Reliance Industries and Adani Group, helmed by two of Asia’s richest tycoons—have the ability to raise vast sums of capital, and the experience and political connections to navigate India’s byzantine bureaucracy. Capitalizing on government subsidies and privatization plans, they are executing projects with a scale and speed that have eluded India in the past.

Among their ventures: A new airport for Mumbai, designed by the firm founded by the late Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid to look like a lotus flower, which is scheduled to start opening next year after the Adani Group took it over. When completed, it’s expected to connect to high-speed rail and handle 90 million passengers annually—only slightly fewer than Atlanta’s main airport, the world’s busiest, last year.

After spending more than $45 billion to build out telecommunications networks, Reliance Industries—a petrochemicals, textiles and retail juggernaut—is constructing factories to make solar panels and batteries for energy storage to position India as a credible alternative to China. It has pledged $75 billion in green-energy spending over the next 15 years.

The 155-year-old Tata Group, which took control of the formerly state-owned Air India last year, recently placed one of the largest orders in aviation history for 470 new aircraft. The salt-to-steel-to-software behemoth, which owns British automaker Jaguar Land Rover, is forging ahead with producing electric vehicles, military transport aircraft, smartphones and telecom hardware, with plans to invest $90 billion in India over five years.

Half a dozen conglomerates now control or have major stakes in 25% of India’s port capacity, 45% of cement production, a third of steel making, nearly 60% of all telecom subscriptions, and more than 45% of coal imports. An analysis by the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy, a research firm, shows that a quarter of all new investment proposals by private companies since 2014 have come from the companies.

“This is the period where it’s not the mad rush of entrepreneurs going out to build new capacities, to become great entrepreneurs—this is the era of great concentration,” said Mahesh Vyas, CMIE’s managing director.

Jun 21, 2023

Riaz Haq

Modi’s Vision for India Rests On Six Giant Companies

https://www.wsj.com/articles/modi-india-economy-reliance-industries...

Is this good for India, especially as it seeks to compete with China? The evidence is mixed. The mammoth firms can lead large breakthrough projects, but rising industrial concentration can also stifle competition and leave India’s plans vulnerable without broader private investment.

“It’s no longer that they’re taking the place of large public-sector firms, they’re now actually expanding at the expense of other private-sector firms,” said Viral Acharya, a former deputy governor of India’s central bank.

Recent research by Acharya, in a Brookings Institution paper, shows the largest conglomerates have since 2015 rapidly grown their market share, giving them greater power over prices for goods and services they sell. Prices have been rising faster than costs in some industries they dominate, such as cement, his research shows.

“People don’t see a point in entering any space where these big corporations are already,” said Rohit Chandra, an assistant professor at the Indian Institute of Technology—Delhi’s School of Public Policy. “You don’t want just a small group of companies winning everything over and over again.”

Together, the firms’ market capitalizations increased an average of 386% in the decade ending in December, more than double the broader market’s growth. Mukesh Ambani, who runs Reliance, is Asia’s wealthiest man. Beyoncé performed at his daughter’s wedding celebrations in 2018.

Gautam Adani, chairman of the Adani Group, became one of Asia’s wealthiest people, though his net worth has plunged this year.

The Adani Group’s tumultuous year so far exemplifies the danger of relying on a small group of conglomerates. A U.S. short seller in January targeted the energy and infrastructure business with allegations of stock manipulation and accounting fraud, leading Adani companies to lose tens of billions of dollars in market value.

The turmoil cast a cloud over the enterprise’s future expansion as it pays down debt to reassure investors. France’s TotalEnergies paused plans to partner with Adani to produce environmentally-friendly green hydrogen, saying in February the Adani Group “has other things to worry about.”

Adani Group has denied allegations that it committed fraud or stock manipulation. The company says it’s still expanding, including plans to redevelop Dharavi, a Mumbai slum featured in the 2008 film “Slumdog Millionaire.”

Academics and economists refer to the firms as “national champions,” a term that’s also been used to describe Chinese state-owned companies and South Korea’s private-sector chaebols. With state backing and coordination, the chaebols helped South Korea industrialize and turned it into an export powerhouse.

India’s model is shaping up to be a variant of the national-champions strategy, said Nouriel Roubini, an economist and emeritus professor at New York University. One difference with South Korea, he said, is that chaebols were nurtured by the state to be internationally competitive, while Indian companies are largely domestic giants.

The Modi government says it isn’t emulating the chaebol model. “I don’t know if Korea gave special dispensation to the chaebols, but in India, everybody competes on an equal footing,” Indian Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal said in an interview.

He said the conglomerates’ advantage comes from the fact that they have a legacy in India, people skills and managerial talent because of their size. “But other than that, all our projects are through transparent bidding mechanisms, and everybody has to compete to be able to get that business,” he said.

Jun 21, 2023

Riaz Haq

Modi’s Vision for India Rests On Six Giant Companies

https://www.wsj.com/articles/modi-india-economy-reliance-industries...

Modi’s supporters say his administration is seeking to partner with the private sector at large, not specific companies. Government policies, they say, have attracted multinationals such as Apple, which is diversifying its supply chains outside China, while also spawning an ecosystem for startups. On a visit to the U.S. this week, Modi is poised to strengthen defense and economic ties between the U.S. and India.

Harish Damodaran, an editor at the independent Indian Express newspaper and author of books on business, uses the term “conglomerate capitalism” to describe the country’s corporate landscape. While the government doesn’t typically direct the companies to make particular investments, he says the centralization of political power under Modi has led to a shift in their favor.

The firms find it easier to deal with a single power center in New Delhi rather than the patchwork of regional political heavyweights that flourished before Modi’s rise, and are aligning their strategies with his goals, he said.

Adani, who has a longstanding relationship with Modi, emerged as a key infrastructure builder over the past decade. His industrial group, India’s largest private port operator, controls a string of seaports and terminals. It is building highways, power-transmission lines and networks to supply natural gas, and modernizing airports that were previously state-run.

An Adani spokesman said the group has created a successful template for infrastructure development that draws on 20,000 vendor companies. A large country like India isn’t dependent on any one conglomerate or group of companies, the spokesman said.

The Tata Group didn’t respond to requests for comment. A Reliance spokesman said its expertise in executing large projects, including the world’s largest oil refinery in Modi’s home state of Gujarat, has benefited India. Reliance executives say it doesn’t receive special treatment from New Delhi, but that Modi’s goals and the goals of Ambani, Reliance’s chairman, overlap.

Reliance’s telecom venture shows what deep-pocketed conglomerates can do—and the potential pitfalls.

In 2010, before Modi became prime minister, Ambani set out to build India’s first 4G, or fourth generation, mobile network, a radical departure from Reliance’s main businesses at the time. Incumbent telecom providers such as Bharti Airtel and Vodafone Group were mostly focused on 3G. Average data prices in India at the time were among the world’s highest.

Launching in 2016, Reliance’s service, called Jio, ran advertisements on newspaper front pages with its blue logo, and below it a photo of Modi, who was elected two years earlier. “Dedicated to India and 1.2 billion Indians,” the ads said. After critics complained about what they called the inappropriate use of Modi’s image, the prime minister’s office said it hadn’t granted Jio permission, and Jio apologized.

Jio initially offered free voice calls and text messages. Unlimited internet data was free for the first six months and after that cost consumers a quarter of the industry average.

The result was a colossal data binge, with hundreds of millions of people getting online for the first time. It also caused a price war with rivals that put many out of business and collapsed competition.

Jio’s subscriptions grew rapidly, and now stand at 430 million, making it the top player. It has attracted billions of dollars of investment from Facebook parent Meta Platforms, Alphabet’s Google, and other investors.

As price wars dragged on, Jio’s rivals—who also faced other regulatory and judicial setbacks—warned that unsustainably low prices were pushing the heavily-indebted industry toward a crisis. India’s government had to step in with a relief package in 2021 that temporarily froze payments the companies must make to New Delhi for using airwaves, among other steps.

Jun 21, 2023