PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

While Fareed Zakaria, Nick Kristoff and other talking heads are still stuck on the old stereotypes of Muslim women, the status of women in Muslim societies is rapidly changing, and there is a silent social revolution taking place with rising number of women joining the workforce and moving up the corporate ladder in Pakistan.

"More of them(women) than ever are finding employment, doing everything from pumping gasoline and serving burgers at McDonald’s to running major corporations", says a report in the latest edition of Businessweek magazine.

Beyond company or government employment, there are a number of NGOs focused on encouraging self-employment and entrepreneurship among Pakistani women by offering skills training and microfinancing. Kashf Foundation led by a woman CEO and BRAC are among such NGOs. They all report that the success and repayment rate among female borrowers is significantly higher than among male borrowers.

In rural Sindh, the PPP-led government is empowering women by granting over 212,864 acres of government-owned agriculture land to landless peasants in the province. Over half of the farm land being given is prime nehri (land irrigated by canals) farm land, and the rest being barani or rain-dependent. About 70 percent of the 5,800 beneficiaries of this gift are women. Other provincial governments, especially the Punjab government have also announced land allotment for women, for which initial surveys are underway, according to ActionAid Pakistan.

Both the public and private sectors are recruiting women in Pakistan's workplaces ranging from Pakistani military, civil service, schools, hospitals, media, advertising, retail, fashion industry, publicly traded companies, banks, technology companies, multinational corporations and NGOs, etc.

Here are some statistics and data that confirm the growth and promotion of women in Pakistan's labor pool:

1. A number of women have moved up into the executive positions, among them Unilever Foods CEO Fariyha Subhani, Engro Fertilizer CFO Naz Khan, Maheen Rahman CEO of IGI Funds and Roshaneh Zafar Founder and CEO of Kashf Foundation.

2. Women now make up 4.6% of board members of Pakistani companies, a tad lower than the 4.7% average in emerging Asia, but higher than 1% in South Korea, 4.1% in India and Indonesia, and 4.2% in Malaysia, according to a February 2011 report on women in the boardrooms.

3. Female employment at KFC in Pakistan has risen 125 percent in the past five years, according to a report in the NY Times.

4. The number of women working at McDonald’s restaurants and the supermarket behemoth Makro has quadrupled since 2006.

5. There are now women taxi drivers in Pakistan. Best known among them is Zahida Kazmi described by the BBC as "clearly a respected presence on the streets of Islamabad".

6. Several women fly helicopters and fighter jets in the military and commercial airliners in the state-owned and private airlines in Pakistan.

Here are a few excerpts from the recent Businessweek story written by Naween Mangi:

About 22 percent of Pakistani females over the age of 10 now work, up from 14 percent a decade ago, government statistics show. Women now hold 78 of the 342 seats in the National Assembly, and in July, Hina Rabbani Khar, 34, became Pakistan’s first female Foreign Minister. “The cultural norms regarding women in the workplace have changed,” says Maheen Rahman, 34, chief executive officer at IGI Funds, which manages some $400 million in assets. Rahman says she plans to keep recruiting more women for her company.

Much of the progress has come because women stay in school longer. More than 42 percent of Pakistan’s 2.6 million high school students last year were girls, up from 30 percent 18 years ago. Women made up about 22 percent of the 68,000 students in Pakistani universities in 1993; today, 47 percent of Pakistan’s 1.1 million university students are women, according to the Higher Education Commission. Half of all MBA graduates hired by Habib Bank, Pakistan’s largest lender, are now women. “Parents are realizing how much better a lifestyle a family can have if girls work,” says Sima Kamil, 54, who oversees 1,400 branches as head of retail banking at Habib. “Every branch I visit has one or two girls from conservative backgrounds,” she says.

Some companies believe hiring women gives them a competitive advantage. Habib Bank says adding female tellers has helped improve customer service at the formerly state-owned lender because the men on staff don’t want to appear rude in front of women. And makers of household products say female staffers help them better understand the needs of their customers. “The buyers for almost all our product ranges are women,” says Fariyha Subhani, 46, CEO of Unilever Pakistan Foods, where 106 of the 872 employees are women. “Having women selling those products makes sense because they themselves are the consumers,” she says.

To attract more women, Unilever last year offered some employees the option to work from home, and the company has run an on-site day-care center since 2003. Engro, which has 100 women in management positions, last year introduced flexible working hours, a day-care center, and a support group where female employees can discuss challenges they encounter. “Today there is more of a focus at companies on diversity,” says Engro Fertilizer CFO Khan, 42. The next step, she says, is ensuring that “more women can reach senior management levels.”

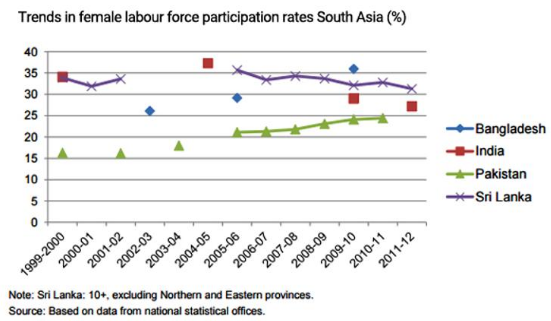

The gender gap in South Asia remains wide, and women in Pakistan still face significant obstacles. But there is now a critical mass of working women at all levels showing the way to other Pakistani women.

I strongly believe that working women have a very positive and transformational impact on society by having fewer children, and by investing more time, money and energies for better nutrition, education and health care of their children. They spend 97 percent of their income and savings on their families, more than twice as much as men who spend only 40 percent on their families, according to Zainab Salbi, Founder, Women for Women International, who recently appeared on CNN's GPS with Fareed Zakaria.

Here's an interesting video titled "Redefining Identity" about Pakistan's young technologists, including women, posted by Lahore-based 5 Rivers Technologies:

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

Status of Women in Pakistan

Microfinancing in Pakistan

Gender Gap Worst in South Asia

Status of Women in India

Female Literacy Lags in South Asia

Land For Landless Women

Are Women Better Off in Pakistan Today?

Growing Insurgency in Swat

Religious Leaders Respond to Domestic Violence

Fighting Agents of Intolerance

A Woman Speaker: Another Token or Real Change

A Tale of Tribal Terror

Mukhtaran Mai-The Movie

World Economic Forum Survey of Gender Gap

"More of them(women) than ever are finding employment, doing everything from pumping gasoline and serving burgers at McDonald’s to running major corporations", says a report in the latest edition of Businessweek magazine.

Beyond company or government employment, there are a number of NGOs focused on encouraging self-employment and entrepreneurship among Pakistani women by offering skills training and microfinancing. Kashf Foundation led by a woman CEO and BRAC are among such NGOs. They all report that the success and repayment rate among female borrowers is significantly higher than among male borrowers.

In rural Sindh, the PPP-led government is empowering women by granting over 212,864 acres of government-owned agriculture land to landless peasants in the province. Over half of the farm land being given is prime nehri (land irrigated by canals) farm land, and the rest being barani or rain-dependent. About 70 percent of the 5,800 beneficiaries of this gift are women. Other provincial governments, especially the Punjab government have also announced land allotment for women, for which initial surveys are underway, according to ActionAid Pakistan.

Both the public and private sectors are recruiting women in Pakistan's workplaces ranging from Pakistani military, civil service, schools, hospitals, media, advertising, retail, fashion industry, publicly traded companies, banks, technology companies, multinational corporations and NGOs, etc.

Here are some statistics and data that confirm the growth and promotion of women in Pakistan's labor pool:

1. A number of women have moved up into the executive positions, among them Unilever Foods CEO Fariyha Subhani, Engro Fertilizer CFO Naz Khan, Maheen Rahman CEO of IGI Funds and Roshaneh Zafar Founder and CEO of Kashf Foundation.

2. Women now make up 4.6% of board members of Pakistani companies, a tad lower than the 4.7% average in emerging Asia, but higher than 1% in South Korea, 4.1% in India and Indonesia, and 4.2% in Malaysia, according to a February 2011 report on women in the boardrooms.

3. Female employment at KFC in Pakistan has risen 125 percent in the past five years, according to a report in the NY Times.

4. The number of women working at McDonald’s restaurants and the supermarket behemoth Makro has quadrupled since 2006.

5. There are now women taxi drivers in Pakistan. Best known among them is Zahida Kazmi described by the BBC as "clearly a respected presence on the streets of Islamabad".

6. Several women fly helicopters and fighter jets in the military and commercial airliners in the state-owned and private airlines in Pakistan.

Here are a few excerpts from the recent Businessweek story written by Naween Mangi:

About 22 percent of Pakistani females over the age of 10 now work, up from 14 percent a decade ago, government statistics show. Women now hold 78 of the 342 seats in the National Assembly, and in July, Hina Rabbani Khar, 34, became Pakistan’s first female Foreign Minister. “The cultural norms regarding women in the workplace have changed,” says Maheen Rahman, 34, chief executive officer at IGI Funds, which manages some $400 million in assets. Rahman says she plans to keep recruiting more women for her company.

Much of the progress has come because women stay in school longer. More than 42 percent of Pakistan’s 2.6 million high school students last year were girls, up from 30 percent 18 years ago. Women made up about 22 percent of the 68,000 students in Pakistani universities in 1993; today, 47 percent of Pakistan’s 1.1 million university students are women, according to the Higher Education Commission. Half of all MBA graduates hired by Habib Bank, Pakistan’s largest lender, are now women. “Parents are realizing how much better a lifestyle a family can have if girls work,” says Sima Kamil, 54, who oversees 1,400 branches as head of retail banking at Habib. “Every branch I visit has one or two girls from conservative backgrounds,” she says.

Some companies believe hiring women gives them a competitive advantage. Habib Bank says adding female tellers has helped improve customer service at the formerly state-owned lender because the men on staff don’t want to appear rude in front of women. And makers of household products say female staffers help them better understand the needs of their customers. “The buyers for almost all our product ranges are women,” says Fariyha Subhani, 46, CEO of Unilever Pakistan Foods, where 106 of the 872 employees are women. “Having women selling those products makes sense because they themselves are the consumers,” she says.

To attract more women, Unilever last year offered some employees the option to work from home, and the company has run an on-site day-care center since 2003. Engro, which has 100 women in management positions, last year introduced flexible working hours, a day-care center, and a support group where female employees can discuss challenges they encounter. “Today there is more of a focus at companies on diversity,” says Engro Fertilizer CFO Khan, 42. The next step, she says, is ensuring that “more women can reach senior management levels.”

The gender gap in South Asia remains wide, and women in Pakistan still face significant obstacles. But there is now a critical mass of working women at all levels showing the way to other Pakistani women.

I strongly believe that working women have a very positive and transformational impact on society by having fewer children, and by investing more time, money and energies for better nutrition, education and health care of their children. They spend 97 percent of their income and savings on their families, more than twice as much as men who spend only 40 percent on their families, according to Zainab Salbi, Founder, Women for Women International, who recently appeared on CNN's GPS with Fareed Zakaria.

Here's an interesting video titled "Redefining Identity" about Pakistan's young technologists, including women, posted by Lahore-based 5 Rivers Technologies:

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

Status of Women in Pakistan

Microfinancing in Pakistan

Gender Gap Worst in South Asia

Status of Women in India

Female Literacy Lags in South Asia

Land For Landless Women

Are Women Better Off in Pakistan Today?

Growing Insurgency in Swat

Religious Leaders Respond to Domestic Violence

Fighting Agents of Intolerance

A Woman Speaker: Another Token or Real Change

A Tale of Tribal Terror

Mukhtaran Mai-The Movie

World Economic Forum Survey of Gender Gap

Riaz Haq

International Women's Day: Growing Presence of Pakistani Women in Science and Technology

http://www.riazhaq.com/2023/03/international-womens-day-growing.html

It is International Women's Day on March 8, and its theme is "DigitALL: Innovation and technology for gender equality". It's a day to highlight Pakistani women's participation in science and technology. Nearly half a million Pakistani women are currently enrolled in science, technology, engineering and mathematics courses at universities, accounting for nearly 46% of all STEM students in higher education institutions in the country. Several Pakistani women are leading the country's tech Startup ecosystem. Others occupy significant positions at world's top research labs, tech firms, universities and other science institutions. They are great role models who are inspiring young Pakistani women to pursue careers in science and technology.

Mar 7, 2023

Riaz Haq

Four key trends - Newspaper - DAWN.COM

https://www.dawn.com/news/1766451

By Umair Javed

The cultural indicators are about how people understand the world around them and the degree to which they are engaged with it. The first of these relates to consumption of information, especially among young people, who constitute a majority in the country. For this, we can turn to Table 40 of the last census, which reports that 60 per cent of households rely on TV and 97pc rely on mobile phones for basic information. The corresponding figures in 1998 were 7pc and 0pc respectively.

What this overwhelmingly young population is watching on TV or through their mobiles is something that we can never completely know. But what is clear is that a lot of information is being accessed, and a lot of ideas — about politics, about religious beliefs, and about the rest of the world — are circulating. Controlling or regulating this flow is an impossibility. Will it lead to an angrier population or a more passive one? A more conservative one or one with some transgressive tendencies? So far, the outcome leans more towards anger and conservatism.

Another slow but steady sociocultural transformation is the vanishing gender gap in higher education. Men and women between the ages of 20 and 35 have university degrees at roughly the same rate (about 11pc). Between 20 and 30, a slightly higher percentage of women have a college degree compared to men. And just two decades ago, women’s higher education attainment in the same 20 to 35 age bracket was 3pc lower than men. This gap has been covered and there are strong signs that it will reverse in the other direction as male educational attainment stagnates.

What does a more educated female population mean for societal functioning? Will these capabilities threaten male honour (and patriarchy) in different ways? Will there be new types of gender politics and conflicts? And will the levee finally break in terms of the barriers that continue to prevent women from gaining dignified remunerated work? As in other unequal countries, Pakistani men hold a monopoly over economic benefits and public space. And they are unlikely to give these privileges up passively.

In the socioeconomic domain, there are also two things worth highlighting. The first is urban migration, not just in large metropolitan centres, but in smaller second- and third-tier cities as well. Fragmenting land holdings and climate change are compelling young men in particular to move to cities in large numbers. A 10-acre farm inherited by five brothers will lead to at least three seeking work outside of agriculture.

The official urbanisation rate may be at around 38pc but this is a significant underestimate. Many villages are now small towns, and small towns are now nothing less than large urban agglomerations. The perimeters of these urban areas are dotted with dense informal settlements that provide shelter — often the only type available — for working-class migrants.

Finally, the last trend is employment status in the labour force. In the last 20 years, the percentage of people earning a living through a daily/weekly/monthly wage (as opposed to being a self-cultivator, self-employed, or running a small business) has increased by 10pc. Much of this increase is taking place in the informal economy and that too in the services sector.

Starting your own business, however small, requires money, which most do not have. Getting higher-paying, formal-sector jobs first requires getting credentials and training, which again is beyond the budget of most. Large swathes of the working population will grind out a living by taking care of the needs of the better off — fixing their cars, cleaning their houses, serving them food. Given the condition of the economy, this trend is unlikely to change.

Jul 24, 2023

Riaz Haq

How the mobile phone is transforming Pakistan - Newspaper - DAWN.COM

https://www.dawn.com/news/1448782

How are we navigating our daily lives, connecting with our surroundings, equipped with the mobile phone?

Faiza Shah Published December 2, 2018

Mehreen Kashif from Larkana, for example, manages a business of hand-embroidered apparel and bed linen without leaving her home. It has been four years since she launched her work-from-home enterprise through a Facebook page and then contacting clients through WhatsApp.

“Women are not allowed to leave home here,” she explains. Owning a mobile phone has been a game-changer, though, as she has been able to expand her business over only four years and that, too, countrywide. Most of her clients are from Punjab, where she also orders fabric from. She has it shipped from Al Karam textile mills in Faisalabad. She simply puts up new designs and items on her WhatsApp status and the orders from her phone contacts pour in. She estimates about 4,000 repeat customers but also claims that they are “unlimited” and “it is almost getting hard to keep up with the orders.”

Mehreen caters to customised orders as well. She has 30 women working for her, and has provided two of them with mobile phones as, “it is easier to share pictures of the designs they work with.” Her effort is to seek out embroiderers with skill but also those who are truly in need of money. And this is a driving force behind managing her business; the ability to employ women who have talent but are house-bound under the dictates of rural traditions.

“They just come to my house for work,” she says of her employees. “The phone has facilitated us living in such an area where women are not allowed to leave their houses. It has helped me because I also do not have permission to go out.”

A similar story is echoed by Salma Ilyas, who runs a kitchen business in Karachi to provide home-cooked meals to “a young professional class”. Mother to four young ones, her husband owned a small business of selling paper. One fine day, the business got wrapped up as the owner of the building housing the paper shop decided to remove all businessmen from the building. With no backup plan, with no storage space for the bundles of paper already bought in wholesale, the Ilyases were in trouble.

“One day, I just cooked achaar gosht and put up pictures on my Facebook wall,” narrates Salma. “People started liking the photos and asked how much for a plate. That sparked an idea to sell what I cook. That week I made almost as much as my husband would make every week in his paper business.”

Things suddenly changed financially for the Ilyases as Salma dragged the family out of its quagmire. With some savings, she upgraded her cooking range, bought better utensils, and went full-time. Her husband now receives orders on WhatsApp and handles the food delivery component of the business. The paper from the old business was sold onwards to someone else. And as Salma puts it, her marriage and domestic harmony seems to be at an all-time high because of WhatsApp.

What is interesting is how travel and restaurant deliveries — 31 percent and 24 percent consumers respectively purchasing within the category — are driving the growth for the evolving mobile industry in Pakistan.”

As with the Ilyases, the mobile phone has brought together the service provider and client, almost eliminating the middleman entirely. Business cards used to be a thing of yesteryear, now it’s the WhatsApp number. The service provider, such as an electrician, a cook, or a car mechanic, gives their mobile number to clients along with a fair bit of reliability. As clients have a mobile number of the electrician or AC repairman, they can catch a hold of him pretty much anytime during working hours. In other words, phones have broadened opportunities for recreation and business alike.

Aug 19, 2023