PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

Gallup Survey Showed 75% of Pakistanis Welcomed 1999 Coup

On October 12, 1999, Pakistani military toppled democratically elected Prime Minister Mian Mohammad Nawaz Sharif. This action followed the Prime Minister's sudden decision to sack Army Chief General Pervez Musharraf and the Prime Minister's simultaneous orders to deny landing permission to the Pakistan International Airlines Boeing 777-200 that was bringing the Army Chief back to Karachi from Colombo, Sri Lanka. Polls conducted immediately after the coup showed broad public support for it.

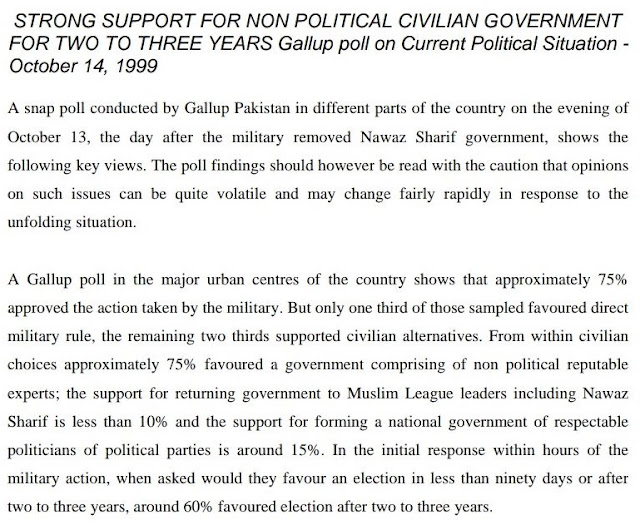

October 1999 Gallup Survey:

A Gallup poll conducted immediately after the coup showed that 75% of respondents supported the military takeover, while less than 10% supported restoring Mr. Nawaz Sharif's government.

|

| Gallup Pakistan Survey Report October 13, 1999. Source: Bilal Gilani |

Benazir Bhutto's Reaction:

It was not just the ordinary Pakistanis who welcomed the coup that toppled Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif's government. Here's how Pakistan's first woman prime minister late Benazir Bhutto reacted to it in 1999:

"Here, a coup has taken place against an unpopular despot (Nawaz Sharif) who was hounding the press, the judiciary, the opposition, the foreign investors. And when he decided to divide the army, the last institution left, the army reacted. Without going into the justifications of who is worse and the frying pan or the fire, I would like to say 'let's move forward'. This is a very dangerous period for a country which has physical bankruptcy and I would like to urge the western community to stay away from Nawaz Sharif, he is not liked by the Pakistani people"

Public Opinion Surveys:

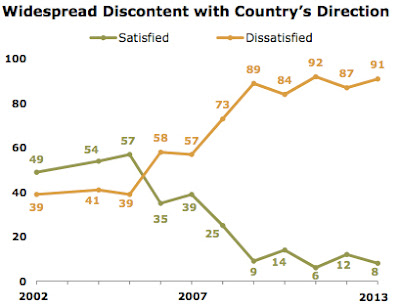

There were frequent public opinion surveys conducted by multiple professional pollsters in Pakistan in the decade that followed the 1999 coup. One such credible survey was done regularly by Pew Global Research. It showed that the majority of the people believed the country was headed in the right direction in Musharraf years. It also showed that people's satisfaction with Pakistan's direction has been in rapid decline. It fell sharply during the governments headed by the Pakistan People's Party.

|

| Source: Pew Research in Pakistan |

Another survey conducted by Gallup Pakistan in August 2013 showed that 59% of Pakistanis have a positive view of President Muaharraf (31% say they hold a favorable opinion of him and another 28% say he was satisfactory). 34% had an unfavorable opinion of the former ruler.

Pakistani Military's Popularity:

Multiple polls conducted over many years in Pakistan have consistently shown that the overwhelming majority of Pakistanis have high confidence in the Pakistani military. This is in sharp contrast to significantly lower levels of confidence they have shown in the country's politicians and bureaucrats. These results appear to reflect the Pakistanis' fear of chaos...the chaos which has hurt them more than any other threat since the country's inception in 1947. Indian Congress leader Mani Shankar Aiyar has described this situation in the following words: "Despite numerous dire forecasts of imminently proving to be a "failed state" Pakistan has survived, bouncing back every now and then as a recognizable democracy with a popularly elected civilian government, the military in the wings but politics very much centre-stage .....the Government of Pakistan remaining in charge, and the military stepping in to rescue the nation from chaos every time Pakistan appeared on the knife's edge". Pakistanis are not alone in their fear of chaos. Chinese, too, fear chaos. "In Chinese political culture, the biggest fear is of chaos", writes Singaporean diplomat Kishore Mahbubani in his recent book entitled "Has China Won".

|

| PILDAT Survey 2015 |

A 2015 poll conducted by Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development (PILDAT) found that 75% of respondents trust the country's military, a much higher percentage than any other institution. Only 36% have confidence in Pakistan's political parties.

|

| Gallup Poll Findings in Pakistan. Source: Gallup International |

Here's a 2014 snapshot of how Pakistanis see various other institutions, according to Gallup International:

|

| Terror Stats in Pakistan. Source: satp.org |

Is India a Paper Elephant?

CPEC & Digital BRI

Pakistan's National Resilience, Success Against COVID19

China-Pakistan Defense Production Collaboration Irks West

Balakot and Kashmir: Fact Checkers Expose Indian Lies

Is Pakistan Ready for War with India?

Pakistan-Made Airplanes Lead Nation's Defense Exports

Modi's Blunders and Delusions

India's Israel Envy: What If Modi Attacks Pakistan?

Project Azm: Pakistan to Develop 5th Generation Fighter Jet

Pakistan Navy Modernization

Pakistan's Sea-Based Second Strike Capability

Who Won the 1965 War? India or Pakistan?

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on October 12, 2020 at 9:05pm

-

Benazir Bhutto in 1999: "Here, a coup has taken place against an unpopular despot (Nawaz Sharif) who was hounding the press, the judiciary, the opposition, the foreign investors. And when he decided to divide the army, the last institution left, the army reacted. Without going into the justifications of who is worse and the frying pan or the fire, I would like to say 'let's move forward'. This is a very dangerous period for a country which has physical bankruptcy and I would like to urge the western community to stay away from Nawaz Sharif, he is not liked by the Pakistani people".

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on October 23, 2020 at 8:05am

-

Breaking an old taboo, Pakistan begins to reckon with its powerful military

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/pakistan-military...

Sharif shocked the country by denouncing the army chief, Gen. Qamar Javed Bajwa, at the first rally of the Pakistan Democratic Movement. In a stunning departure from Pakistani norms, the three-time premier accused Bajwa of backing his removal from office on corruption charges in 2017 and rigging the 2018 elections. It was the first time an establishment politician had ever made such accusations.

“General Qamar Javed Bajwa, you packed up our government and put the nation at the altar of your wishes,” Sharif said in Urdu. “You rejected the people’s choice in the elections and installed an inefficient and incapable group of people,” leading to an economic catastrophe. “General Bajwa, you will have to answer for inflated electricity bills, shortage of medicines and poor people suffering.”

-------------

There are also signs that some alliance members are not comfortable with Sharif’s anti-military diatribe. On Saturday, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, chairman of the Pakistan People’s Party and son of slain former prime minister Benazir Bhutto, called the military establishment “part of history” and said it was “regrettable” that Sharif had mentioned any of its generals by name.

“We do not want their morale to go down,” he said of the armed forces. “We want a real and complete democracy, but we do not look to the umpire’s finger, we look to the people’s signal.”

Even Sharif’s outspoken daughter, Maryam, who lives in Pakistan and whose husband was arrested briefly Monday after the rally in Karachi, has stressed that she is not “anti-military.”

Hasan Askari Rizvi, a political analyst in Lahore, predicted that while the current confrontation could weaken Khan politically, it might actually increase the military’s influence.

“Traditionally, Pakistan has been a security state whose survival was the foremost concern,” Rizvi said. He noted that even today, “inefficient” civilian rulers continue to rely on the army for emergency and humanitarian interventions.

“The political forces were always weak and divided,” he said. “Now this division is getting wider, which will harm democratic institutions, too.”

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on October 30, 2020 at 5:48pm

-

The TED website describes Kishore Mahbubani, a career diplomat from Singapore, as someone who “re-envisions global power dynamics through the lens of rising Asian economies.” This description is not just apt for Mahbubani but also for his new book, “Has the West Lost It?” The title may appear controversial to a reader unfamiliar with world politics and history, but is is a treatise for the future. In less than 100 pages, the author carefully puts together reasons for the Western world’s demise and suggests a three-pronged solution for a better world, where the gap between East and West is bridged to a large extent

https://www.fairobserver.com/region/asia_pacific/us-uk-china-india-...

In “Has the West Lost It?” Mahbubani dispels myths around Asian countries such as Malaysia, Bangladesh and Pakistan, which have achieved tremendous growth in the last 30 years. On the other hand, the Western world has failed to take care of its working class, which has been forced to the fringes. Mahbubani argues that the rise of countries like China and India mean that the West is no longer the most dominant force in world politics, and that it now has to learn to share, even abandon, its position and adapt to a world it can no longer dominate.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on October 30, 2020 at 6:09pm

-

Excerpts of "Has the West Lost It?" by Kishore Mahbubani

This is also why many Asian countries, including hitherto troubled countries like Burma (Myanmar) and Bangladesh, Pakistan and the Philippines, are progressing slowly and steadily. In each of these four countries, various forms of dictatorship have been replaced by leaders who believe that they are accountable to their populations. Many of their troubles continue, but poverty has diminished significantly, the middle classes are growing and modern education is spreading. There are no perfect democracies in Asia (and, as we have learned after Trump and Brexit, democracies in the West are deficient, too).

----------

Pakistan is one of the most troubled countries in the world. Virtually no one sees Pakistan as a symbol of hope. Yet, despite being thrust into the frontlines by George W. Bush after 9/11 in 2001 and forced to join the battle against the Taliban, ‘Pakistan experienced a “staggering fall” in poverty from 2002 to 2014, according to the World Bank, halving to 29.5 per cent of the population.’25 In the same period, the middle-class population soared.

-------------

When countries like Bangladesh and Pakistan have begun marching steadily towards middle-class status for a significant part of their populations, the world has turned a corner. Indeed, the statistics for the growth of middle classes globally are staggering. From a base of 1.8 billion in 2009, the number will hit 3.2 billion by 2020. By 2030, the number will hit 4.9 billion,27 which means that more than half the world’s population will enjoy middle-class living standards by then.

------------------------

No other region can show such a sharp contrast between its dysfunctional past and its functional future, but Southeast Asia is not an exception. South Asia, another strife-ridden area, now probably has only one dysfunctional government, Nepal. As documented earlier, even Pakistan and Bangladesh are progressing slowly and steadily. In the neighbouring Gulf region, the news focuses on the conflict in Yemen. Yet, next door to Yemen, another nation, Oman, has been gradually making progress for decades. Oman’s per capita GDP has increased from US $9,907 in 1980 to US $15,965 in 2015.33

-----------------

Take the Islamic world, for example. They feel that the West has become trigger-happy since the end of the Cold War, and they resent it. Even worse, most of the countries recently bombed by the West have been Muslim countries, including Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen. This is why many of the 1.5 billion Muslims believe that Muslim lives don’t matter to the West. As indicated earlier, the West needs to pose to itself a delicate and potentially explosive question: is there any correlation between the rise of Western bombing of Islamic societies and the rise of terrorist incidents in the West? It would be foolish to suggest an answer from both extremes: that there is an absolute correlation or zero correlation. The truth is probably somewhere in the middle. If so, isn’t it wiser for the West to reduce its entanglements in the Islamic world? Some of these entanglements have been very unwise. During the Cold War, the CIA instigated the creation of Al-Qaeda to fight the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. The same organization bit the hand that fed it by attacking the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001. Sadly, America didn’t learn the lesson from this mistake. In an effort to remove Assad in Syria, the Obama administration transported ISIS fighters from Afghanistan to Syria to fight Assad.58 To ensure that the ISIS fighters had enough funding, America didn’t bomb the oil exports from ISIS-controlled zones in Syria to Turkey. Through all this, America declared that it was opposed to ISIS. In fact, some American agencies were supporting them, directly or indirectly.59

------------------

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 26, 2020 at 7:06am

-

An army draws its strength from the people it is protecting. It is a bond of absolute trust. Nobody puts their life online for the salaries they are paid. The passion to take to the field of battle is rooted in love for the motherland and its people

https://twitter.com/fsherjan/status/1342803343551451136?s=20

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on January 26, 2021 at 4:41pm

-

The (Pakistani) military therefore provides opportunities which the Pakistani economy cannot, and a position in the officer corps is immensely prized by the sons of shopkeepers and bigger farmers across Punjab and the NWFP. This allows the military to pick the very best recruits, and increases their sense of belonging to an elite. In the last years of British rule and the first years of Pakistan, most officers were recruited from the landed gentry and upper middle classes. These are still represented by figures such as former Chief of Army Staff General Jehangir Karamat, but a much more typical figure is the present COAS (as of 2010), General Ashfaq Kayani, son of an NCO. This social change reflects reflects partly the withdrawal of the upper middle classes to more comfortable professions, but also the immense increase in the numbers of officers required. Meanwhile, the political parties continue to be dominated by ‘feudal’ landowners and wealthy urban bosses, many of them not just corrupt but barely educated. This increases the sense of superiority to the politicians in the officer corps – something that I have heard from many officers and which was very marked in General Musharraf’s personal contempt for Benazir Bhutto and her husband. I have also been told by a number of officers and members of military families that ‘the officers’ mess is the most democratic institution in Pakistan, because its members are superior and junior during the day, but in the evening are comrades. That is something we have inherited from the British.’18 This may seem like a very strange statement, until one remembers that, in Pakistan, saying that something is the most spiritually democratic institution isn’t saying very much. Pakistani society is permeated by a culture of deference to superiors, starting with elders within the family and kinship group. As Stephen Lyon writes: Asymmetrical power relations form the cornerstone of Pakistani society . . . Close relations of equality are problematic for Pakistanis and seem to occur only in very limited conditions. In general, when Pakistanis meet, they weigh up the status of the person in front of them and behave accordingly.19 Pakistan’s dynastically ruled ‘democratic’ political parties exemplify this deference to inheritance and wealth; while in the army, as an officer told me: You rise on merit – well, mostly – not by inheritance,inheritance, and you salute the military rank and not the sardar or pir who has inherited his position from his father, or the businessman’s money. These days, many of the generals are the sons of clerks and shopkeepers, or if they are from military families, they are the sons of havildars [NCOs]. It doesn’t matter. The point is that they are generals.

Lieven, Anatol. Pakistan (pp. 181-182). PublicAffairs. Kindle Edition.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on February 19, 2021 at 9:08am

-

@ejazhaider employs the Quaid I Azam University’s struggle against illegal occupation of its land to illustrate the complexity of the civ-mil equation. Having approached all civilian fora without success, who else is left to appeal to but the military?

https://www.thefridaytimes.com/qau-and-civilian-supremacy/

Years ago, I had coopted Dr Ilhan Niaz for a report on civil-military relations. After we had finalised the report, he sent me an email with some very interesting points. Here’s a gist: There are three types of states. The first are civilian states. The military is either no longer or never was integral to the political order of the state in the domestic sphere. Ilhan’s point was that many of the theorists I had cited in the report belonged to such states and regarded “their exceptional circumstances as normal and desirable.” His second type was civilian-led states. In such states “the military remains an integral component of the political order of the state, a major aspect of the ability of such states to maintain their coherence, and a guarantor of the ultimate state writ and sovereignty.” He cited the example of the French Fifth Republic, Russia, constitutional-democratic India, and market-socialist China as politically-diverse examples of this second type. One can say that many of the Latin American and South East Asian states would also fall into this category.

--------------

n its 73- or 74-year-old (depends on which school of counting one prefers) chequered political history, this country has constantly grappled with the issue of civilian control and supremacy. We currently have the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM), a loose opposition alliance of ideologically disparate political parties, agitating the issue against the sitting government which is referred to, pejoratively, as a ‘hybrid’ set-up.

However, neither the PDM nor the sitting government offers us a definition of democracy and civilian control. The Pakistan Tehreek-e Insaf (PTI) government is essentially a hybrid both in how it was conceived and how it has worked since its conception. That fact notwithstanding, it claims that it won the elections and, therefore, is a legitimate government. It also claims, not without irony — given the hybrid sobriquet for it — that it has the support of all institutions wherein it is quite right. Whether that serves to enhance its legitimacy or otherwise depends on whether one is a PTI or a PDM supporter.

The PDM, on the other hand, starts by making the same claim: vote ko izzat dau (respect people’s electoral choice). But by this it means something quite different — i.e., former prime minister Nawaz Sharif was disqualified and ousted under a plan, PTI was made to win according to the same plan and Mr Sharif pushed to the sidelines because he wanted to exercise the control that is constitutionally due a prime minister without interference from a praetorian army. In other words, civilian supremacy.

At this point, the PDM’s narrative also gets traction because of the poor performance of the PTI government. Barring the dyed-in-the-wool partisan, even informed PTI supporters acknowledge that this government hasn’t covered itself in glory.

----

So, if civilian supremacy does not automatically give us democracy, what exactly is democracy? PDM says it’s about people’s electoral choices. Is that enough? Are we referring to someone or a system giving people a choice as a standalone, decontextualised virtue? What if I am given 10 choices, neither of which is to my liking? Should we then, before we begin to use certain terms, define them more carefully not only for what they must contain intrinsically but also with reference to the context? Put another way, if a system is structured badly and offers a bind, does it even matter how many choices one might get within that system.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on February 19, 2021 at 9:14am

-

In conclusion, weak political institutions and parties and incompetent leadership as well as the country’s geography and demography contribute to governmental failings and complex civil-military relations in Pakistan. This reality is reflected in public opinion polls that show a low level of trust in the government at 36 percent along with parliament, 27 percent; political parties, 30 percent; and politicians, 27 percent. In this context the most trusted institution in the country is Pakistan’s army, which is trusted by 82 percent of the population. But despite the lack of confidence in political intuitions and high trust in the army, most Pakistanis do trust democracy. According to a December 2017 Gallup Poll, 81 percent of Pakistanis prefer democracy, while only 19 percent would rather have a military dictatorship. Recent electoral developments suggest that Pakistan may be heading towards sustainable democracy.

https://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/pakistans-civil-military-relations

Pakistan’s civilian government has little control over the country’s powerful army which stands out as a most trusted institution, with more than 80 percent public approval, compared to 36 percent approval for government. Weak institutions that fail to address Pakistan’s challenges have allowed the army to become more assertive, explains Riaz Hassan, research professor and director of the International Centre for Muslim and Non-Muslim Understanding, and he argues that demography has a role: “The most striking aspect of Pakistan’s demography is that it is made up of six ‘nations,’ each divided between two or, in the case of Balochis, three countries,” he writes. “All are predominantly Islamic, but also endowed with their own distinct, historically grounded cultural identities.” Despite governmental failings and difficult civil-military relations in Pakistan, public polling indicates strong support for democracy, at 80 percent, rather than for a military dictatorship. – YaleGlobal

https://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/pakistans-civil-military-relations

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 31, 2021 at 12:20pm

-

Richard Harris vs George Fulton: Two white men battle out their 'love' for Pakistan

https://images.dawn.com/news/1186887/richard-harris-vs-george-fulto...

As we have conversations about white privilege, gora complex, fake accounts pretending to be tourists, and the weight of the opinions anyone with a lighter skin tone holds in the country — two white men living in Pakistan, Richard Harris and George Fulton, have decided to debate who is allowed to have an opinion about the country.

Before announcing the 'Mother of All Debates,' both men had been critiquing each other on social media. They finally decided to face off in a debate and decide once and for all whether they should be allowed to speak about Pakistan as much as Pakistanis.

-----------------

"What really got to me was that when someone accuses someone of being paid to push a narrative or express their views, I just find it very offensive," Harris began.

"Why is it so difficult for people to comprehend that someone can have a right of centre view of Pakistan, someone can be pro-fauj or someone can have what people say, extra patriotic views about Pakistan? What's so strange about that? Can these views not be held independently? Is Pakistan so unlovable that if someone expresses these views, people are surprised by it?" he questioned.

Belgian Harris went on to reveal that he came to Pakistan as a seven-year-old and is Pakistani. Since his kids are living and studying here, he is passionate about the country's conditions, transitioning from London to Lahore during Covid period.

Fulton, who is a Brit, is in a similar situation. Having been here for 20 years, he referred to the country as a "child" he'd want to see succeed and wish the best for. "At times you are critical of it and at times you tell it off for making mistakes and those who say you can't criticise a country are only advocating nationalism."

The audience was clearly enjoying the debate

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on April 11, 2021 at 10:35am

-

Full Q&A: ‘Rule Makers, Rule Breakers’ author Michele Gelfand on Recode Decode

Gelfand studies why some cultures desire rules, why others avoid them and what gets the best results.

https://www.vox.com/2018/11/28/18115426/michele-gelfand-rule-makers...

A distinguished professor at the University of Maryland, Gelfand studies why different cultures (in families, in different countries and within companies) accept different levels of rule-making. On the corporate level, she said an overly strict rule-abiding culture can lead to PR disasters like United Airlines dragging a paying passenger off one of its planes. But that doesn’t mean the inverse is the right way to go, either.

----------

I started seeing some of these contrasts, so I wanted to try to actually assess it with surveys first, in this case it was across 30 nations, try to put countries on a continuum. Even though all cultures have tight and loose elements, their rule makers and rule breakers, some cultures — in our data, Japan, Germany, Austria, Pakistan — had much stronger rules. And other cultures — like New Zealand, Netherlands, the United States in general, Brazil, Greece — they were much more permissive.

I was really interested in, why did this evolve? It has to have some functionality. So, I started measuring, as I was collecting this data across 30 countries, 7,000 people, the history of these nations. How many times has the place been invaded in the last 100 years? Japan has had a lot of conflict. Germany’s had a lot of conflict. United States, we’ve had our conflicts, but we haven’t been worried about Mexico or Canada invading us for centuries.

I also measured population density. How many people per square mile? Places like Singapore have 20,000 people per square mile. Places like New Zealand have 50 people per square mile, more sheep per capita than people. Even as far back as 1500, like, how many people were living in these places?

And I measured natural disasters, mother nature’s fury. How many times have you had to deal with disasters that other places don’t have to succumb to?

------------

I’ll just give an example. We did this very simple technique where we collected daily diaries from people in the United States and people in Pakistan. And they have really extreme stereotypes of each other. Pakistanis think Americans are half naked all the time. They don’t just think we’re loose, they think we’re exceedingly loose. Americans think Pakistanis ...

If they think of Pakistanis at all.

Yeah, if they know where it is.

And if they think of it in any way, whatsoever.

Yeah, that’s right. That’s right, because we’re really ...

“Aren’t they Indians?” You know ...

I mean, there was the question of like, “Where is that?”

Ugh, they don’t know where it is.

They don’t think about Pakistanis as playing sports or reading poetry. They think about them as excessively tight. So what we did was a very simple intervention to get them out of those echo chambers, because they just meet in the media. They don’t see each other for their daily lives. We randomly assigned people in Pakistan ...

They “meet in the media” is a really good point.

Yeah, they, I mean, we can easily within a week ...

“The media!”

They’re bad. Big bad wolf. We basically gave them, for a week’s time, in Pakistan, daily diaries of Americans. They were not edited, so people were still waking up with their girlfriends and still drinking more. Americans saw daily diaries of Pakistanis. They were still in the mosques more, but they saw so much broader range of situations that they were in.

By the end of the study, the cultural distance that they perceived between each other was dramatically reduced. The stereotypes that they had of each other was dramatically reduced, and they said things ...

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Pakistani Student Enrollment in US Universities Hits All Time High

Pakistani student enrollment in America's institutions of higher learning rose 16% last year, outpacing the record 12% growth in the number of international students hosted by the country. This puts Pakistan among eight sources in the top 20 countries with the largest increases in US enrollment. India saw the biggest increase at 35%, followed by Ghana 32%, Bangladesh and…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on April 1, 2024 at 5:00pm

Agriculture, Caste, Religion and Happiness in South Asia

Pakistan's agriculture sector GDP grew at a rate of 5.2% in the October-December 2023 quarter, according to the government figures. This is a rare bright spot in the overall national economy that showed just 1% growth during the quarter. Strong performance of the farm sector gives the much needed boost for about …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on March 29, 2024 at 8:00pm

© 2024 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network