PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

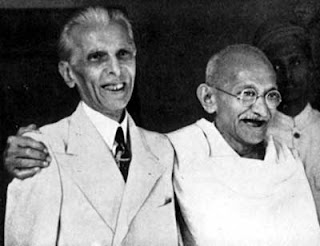

Jaswant Acknowledges Quaid-e-Azam MA Jinnah as a "Great Indian"

Gandhi himself called Jinnah a great Indian. Why don't we recognize that?

Jinnah stood against the might of the Congress party and against the British who didn't really like him.

Jinnah was not against Hindus.

Indian Muslims are treated as aliens.

Nehru's insistence on centralized system led to India's partition.

Senior BJP leader Jaswant Singh has said Pakistan's founder Mohammad Ali Jinnah was "demonized" by India even though it was Jawaharlal Nehru whose belief in a centralized system had led to the Partition.

Jaswant, whose book "Jinnah - India, Partition, Independence", will is being released today, also said Indian Muslims are treated as aliens.

"Oh yes, because he created something out of nothing and single-handedly he stood against the might of the Congress party and against the British who didn't really like him...Gandhi himself called Jinnah a great Indian. Why don't we recognize that? Why don't we see (and try to understand) why he called him that," Singh said, when asked by Karan Thapar in an interview whether he viewed Jinnah as a great man.

He said he did not subscribe to the popular "demonization" of Jinnah.

Singh, a former external affairs minister, feels India had misunderstood Jinnah and made a demon out of him.

Contrary to popular perception, Singh feels it was not Jinnah but Nehru's "highly centralized polity" that led to the Partition of India.

Asked if he was concerned that Nehru's heirs and the Congress party would be critical of the responsibility he was attributing to Nehru for Partition, Singh said, "I am not blaming anybody. I am not assigning blame. I am simply recalling what I have found as the development of issues and events of that period."

Singh contested the popular Indian view that Jinnah was the villain of Partition or the man principally responsible for it. Maintaining that this view was wrong, he said, "It is. It is not borne out of the facts...we need to correct it."

He feels Jinnah's call for Pakistan was "a negotiating tactic" to obtain "space" for Muslims "in a reassuring system" where they would not be dominated by the Hindu majority.

He said if the final decisions had been taken by Mahatma Gandhi, Rajaji or Maulana Azad -- rather than Nehru -- a united India would have been attained, he said, "Yes, I believe so. We could have (attained an united India)."

Singh said the widespread opinion that Jinnah was against Hindus is mistaken.

When told that his views on Jinnah may not be to the liking of his party, he replied, "I did not write this book as a BJP parliamentarian. I wrote this book as an Indian...this is not a party document. My party knows I have been working on this."

Singh also spoke about Indian Muslims who, he said, "have paid the price of Partition". In a particularly outspoken answer, he said India treats them as "aliens".

"Look into the eyes of the Muslims who live in India and if you truly see the pain with which they live, to which land do they belong? We treat them as aliens...without doubt Muslims have paid the price of Partition. They could have been significantly stronger in a united India...of course Pakistan and Bangladesh won't like what I am saying.

In his book, Singh says Pakistan's "induced" sense of hostility to New Delhi is now somewhat "mellowed" and it is ready to accept a greater understanding of the many oneness that bond it with India. However, he admits Pakistan had chosen terror as an instrument of state policy to be used as a tool of oppression.

"...nemesis had to visit upon such policy planks; that malevolent energy of terror, by whatever name you choose to call it, once unleashed had to turn back upon its creator and to begin devouring it," Singh writes in "Jinnah - India, Partition, Independence", which will hit the stands tomorrow.

"This has now converted Pakistan into the epicenter of global terrorism, sadly, therefore, Talibanization now eats into the very vitals of Pakistan," the 669-page book says.

"Its (Pakistan's) induced and perpetual sense of hostility to India is now somewhat mellowed, it is more confident of itself, therefore, accommodative and is now ready to accept a greater understanding of the many oneness and unities that bond India and Pakistan together. Or is it really ready? Dare I ask?" Singh questions.

The BJP, however, maintains that Pakistan has been responsible for terrorist acts against India by elements trained and funded from its soil.

Source: ExpressBuzz India

Related Links:

Iqbal and Jinnah

Jinnah's Pakistan Booms Amidst Doom and Gloom

Quaid-e-Azam M.A. Jinnah's Vision of Pakistan

Eleven Days in Karachi, Pakistan

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 26, 2015 at 7:29am

-

Op Ed by Uday Mahurkar:

It is said that to label a patriot as non-patriot is one of the greatest sins. Against the backdrop of this adage there is the curious case of Abul Kalam Azad, India’s first education minister and a nationalist Muslim credited with steering the boat of the Congress and, by that virtue, of India during the most difficult phase of the Pakistan movement from 1939 to 1945 under the shadow of World War II. There is a significant section of responsible Indians who believe that Azad and his ideological friends belonging to the Wahabi stream - the Deobandi Muslim leaders of that period - opposed Partition because they felt territorial nationalism had no place in Islam since the faith stood for converting the entire world and that the division of India would divide Muslim strength and awaken Hindus from a deep slumber under Muslim rule to the dangers of Pan-Islamism.

One of those who thought so was late retired bureaucrat, and a witness to the Partition, Yuvraj Krishen. His landmark book Understanding Partition is a good read on the actions and objectives of the Muslim League on one hand and, on the other, the Deobandis with their favourite Azad - who were in the Congress. Writing a guest column on the Partition for India Today in 2007, Krishen wrote:

"There is ample evidence now to prove that nationalist Muslims like Abul Kalam Azad and the then Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind president Ahmad Hussain Madani opposed Pakistan only because they felt that Partition would affect Muslim domination in the sub-continent and Muslims would heavily lose. Plus they tried to extract a heavy price from the Congress for their patriotism in the name of minority protection. Congress leaders have tried to hide the fact that as Congress president in 1945, Azad even went to the extent of agreeing to a proposal of rotating Indian headship. It meant India would have a Hindu and then a Muslim head of State and army chief by turns. So, eventually Gandhi and Nehru made Congress a hostage to ‘Hindu-Muslim unity at any cost’ which Jinnah skillfully exploited and got more concessions from the Congress to establish parity in numbers between Hindu and Muslim representation."

But a better way to look at Azad is from the eyes of secular and lslamic scholars/leaders of Pakistan. Amongst them the leaders of the Wahabi stream in Pakistan, generally opposed to Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s modernist approach, see Azad with respect while the Jinnah admirers see him as the representative of an unbending, orthodox and even retrograde brand of Islam and question Gandhiji for taking the support of retrograde Islamic forces. This can be gleaned from the writings and speeches of Wahabi stream leaders like late Tanzeem-e-Islami's (an Islamic socio-political body in Pakistan) Ameer Israr Ahmed and Jamat-e-Ulema-e-Islam president and Deobandi leader Fazlur Rehman and pro-Jinnah, liberal scholars like Ayesha Jalal - who teaches history in United States. Among other such supporters include Hamza Alavi, the eminent late Pakistani social scientist, Naeem Ahmad, an expert on the Pakistan movement and Sharif-Al-Mujahid, a well known Pakistani academic and freedom movement scholar.

http://www.dailyo.in/politics/maulana-abdul-kalam-azad-partition-pa...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on October 4, 2015 at 4:36pm

-

Faisal Devji's review of Venkat Dhulipala’s book "Creating a New Medina":

Now to say that Pakistan was “insufficiently imagined” as a nation-state is not to claim, as Dhulipala seems to think, that it was unintended or lacked a positive character. Indeed I have argued in my own book on Muslim nationalism that for a number of historical reasons, it took an ambiguous if not contradictory form by founding a state outside the legitimising vocabulary of blood and soil, history and geography, to focus on ideas alone. And it was precisely because this “ideological” way of imagining a new society possessed so little juridical precedent or political context, that it proved so difficult to mould into a nation-state. Dhulipala, however, is not concerned with the novelty of this political vision – and in fact thinks it to be neither very original nor even political – but instead nothing more than old-fashioned religion, which, in an equally archaic notion, he imagines as filling the masses with “enthusiasm” (p. 354). ...

------------

While Dhulipala is not above suggesting that historians like Ayesha Jalal are disingenuous in their use of sources, if not entirely ignorant of them, his own narrative is full of such evasions. Correctly describing Ambedkar as the great theorist and critic of Pakistan, for instance, Dhulipala offers us one of his extended summaries of the Dalit leader’s book, Thoughts on Pakistan, which serves as an example of his mode of analysis. By having the text “speak for itself” he can report without comment those passages in which Ambedkar deploys the repertoire of colonial scholarship to paint Muslims as a religious and military threat to Hindus, whose exclusion from India can only be welcomed. Instead of accounting for such hyperbolic statements by locating them within Ambedkar’s political rhetoric, where they are arguably meant to frighten upper castes into turning to Dalits for support, Dhulipala merely declares them to be Ambedkar’s “own beliefs” (p. 135). How, then, are we to account for his good relations with Jinnah, whose statement, that Ambedkar wanted Dalits to replace Muslims as the favored subjects of quotas in a partitioned India, is passed over in silence? Or the support Ambedkar enjoyed from the Muslim League before and after his book was published? Dhulipala doesn’t mention this, just as he doesn’t tell us, when describing with horror the “Day of Deliverance” Jinnah declared to celebrate Congress’s resignation of government in 1939, that both Ambedkar and Savarkar joined in the festivities.

In the time-tested way of old-fashioned national history, Dhulipala’s book depoliticises Muslim nationalism by making it out to be a religious phenomenon at the popular level. Of course Shahid Amin’s Event, Metaphor, Memory manages to do the same for Gandhi’s first movement of Non-Cooperation, but without suggesting that Congress and its leaders were therefore depoliticised or in thrall to Hindu “enthusiasm”. The author of Creating a New Medina separates the Muslim League from all other parties and politics in India, as indeed the world, to stand alone as the unique but still inexplicable villain of the story of partition, which has now surely become one of the most boring subjects in Indian historical writing. Having myself written a book severely critical of the idea of Pakistan, I am not caviling at Dhulipala’s political allegiances, but find his argument to be anachronistic in its subject and scope, and therefore singularly unproductive intellectually. Is the kind of history written by young scholars like Dhulipala going to be reduced to waging old wars with equally ageing analytical equipment? Or maybe it is only in the intellectually impoverished field of Pakistani history that a book like this can be published.

http://thewire.in/2015/10/04/young-fogeys-the-anachronism-of-new-sc...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on October 15, 2016 at 10:14pm

-

Karan Thapar interview with Saeed Naqvi, author of "Being the Other: Muslim in India".

Here is the nub of that narrative: pre-Partition north India with its 'composite culture' was a golden time. Naqvi grew up in a rich family but one having to face up to downward mobility. The Naqvis had known the Nehrus and were with the Congress. They considered Nehru a messiah. Independence arrived. For the Naqvis, though, there was "no celebration" for with Independence came Partition and loss. However, for "'Mishraji' or 'Guptaji'", Naqvi writes, Partition was "a happy outcome". Yet, the doxa, the received opinion, continues to propagate that Jinnah and the Muslims partitioned India. Chapter 3 confronts that doxa to argue how the Congress stalwarts favoured, even desired, Partition. Under scrutiny is not only Sardar Patel but also Nehru and Gandhi. Partition was "the gift the Congress gave to the Hindu Right, which?is today's Hindutva". Later, we hear Atal Bihari Vajpayee say: "Partition was good for Hindus because we now have fewer Muslims to manage."

----------

Returning to Naqvi's point about returning to our founding fathers, it is a paradox compounded. Naqvi himself details how Nehru let Muslims down over the acceptance of Partition, and over the anti-Muslim pogroms in Hyderabad and Jammu. The genesis of the Babri Masjid controversy was in Nehru's time. Naqvi is also aghast at Gandhi's acceptance of Partition. He quotes Gandhi's letter urging the exclusion of Abul Kalam Azad from the cabinet and putting another Muslim in his place. Naqvi names it as "secular pretence". Which founding father, then, to return to?

http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/muslim-in-india-saeed-naqvi-book...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QQGFtMYMoys

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on April 12, 2017 at 8:11am

-

Excerpts of Pakistani historian Ayesha Jalal's interview:

http://herald.dawn.com/news/1153717

Jinnah did not want Partition, in case people have forgotten that, Similarly, when the United Bengal plan was floated, Jinnah said it was better that Bengal remained united.

Jinnah was from a province where Muslims were in a minority. He wanted to use the power of the areas where the Muslims were a majority to create a shield of protection for where they were in a minority. The possibility that the areas that became Pakistan would offer a kind of protection for Muslims living in areas which have remained in India was not acceptable to the Congress. It was easier for them to partition the subcontinent and let these areas go.

There were two steps in Jinnah's strategy. The first was the consolidation of Muslim majority areas behind the All-India Muslim League and then to use undivided Punjab and Bengal as a weight to negotiate an arrangement for all the Muslims at an all– India level. But the Congress had Punjab and Bengal partitioned [to frustrate the first element of his strategy].

All politicians and parties are limited and restricted by their rank and file in some ways. One very important limitation that led to the acceptance of Partition by the Congress can be identified in the interim government's so-called 'poor man's budget' [in 1946] which we all know was not the brain child of Liaquat Ali Khan, but of the finance department The Congress supporters in business wouldn't tolerate that. They thought the budget was untenable. The other limitation was the scale of communal violence. Increase in violence decreased room for the Congress leadership to negotiate a compromise. Every out break of violence hardened the Congress position.

The Congress lacked imagination as far as mass contact with Muslims was concerned. Secondly, even men like Maulana Abul Kalam Azad were saying until the end that the Muslim Question was a psychological one rather than a political one. When Jawaharlal Nehru made the plea for Partition as opposed to sharing power, Azad was still arguing that the Congress should make some concessions to keep the Muslims within India. But then he was sidelined by Gandhi and others.

The Congress basically cut the Muslim problem down to size through Partition. But, in the process, it threw us out of India. Our cultural heritage is all there. Jinnah never gave up on that heritage. He fought tooth and nail that the name "India" should not be allotted to the Congress. He called the place Hindustan until he lost.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 25, 2017 at 7:55pm

-

Husain Haqqani and journalists like Margaret Bourke-White cited by him who attack Jinnah are like little pygmies trying to denigrate a giant of history.

“Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a nation-state. Mohammad Ali Jinnah did all three.”― Stanley Wolpert, Jinnah of Pakistan

https://books.google.com/books?id=d0PqPAAACAAJ&dq=Stanley+Wolpe...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on October 29, 2018 at 7:34am

-

Indians were equally responsible for Partition, not just Pakistan or British: Hamid Ansari

https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/indians-were-equally-responsi...

Former Vice President Hamid Ansari said while people like to hold Pakistan or the British responsible for India's partition, no one wants to admit that India was equally responsible for it.

Referring to a speech delivered by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel's on August 11, 1947, four days before India got its independence, Ansari said in that speech, Patel had said "he took these extreme steps after great deliberation".

Ansari claimed that Patel in this speech also said that "despite his previous opposition to Partition, he was convinced that to keep India united, it must be divided".

He said these speeches are available in Patel's records.

"But as politics of the country changed, someone had to be blamed. So Muslims became the scapegoat and were blamed for Partition," Ansari said.

Meanwhile, the Bharatiya Janta Party has hit out at Ansari. BJP spokesperson Sambit Patra demanded an apology from Ansari for his comments.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 8, 2020 at 4:59pm

-

Hindu nationalism has been the bedrock of the Indian State and polity. Nehruvian secularism was the fringe

by Prof Abhinav Prakash Singh

Delhi University

https://www.hindustantimes.com/columns/ayodhya-marks-the-twilight-o...

The first Republic was founded on the myth of a secular-socialist India supposedly born out of the anti-colonial struggle. However, the Indian freedom movement was always a Hindu movement. From its origin, symbolism, language, and support base, it was the continuation of a Hindu resurgence already underway, but which was disrupted by the British conquest. The coming together of various pagan traditions in the Indian subcontinent under the umbrella of Hinduism is a long-drawn-out process. But it began to consolidate as a unified political entity in the colonial era in the form of Hindutva. The Hindutva concept is driven by an attempt by the older pagan traditions, united by a dharmic framework and intertwined by puranas, myths and folklore, to navigate the modern political and intellectual landscape dominated by nations and nation-states.

Hindutva is not Hinduism. Hindutva is a Hindu political response to political Islam and Western imperialism. It seeks to forge Hindus into a modern nation and create a powerful industrial State that can put an end to centuries of persecution that accelerated sharply over the past 100 years when the Hindu-Sikh presence was expunged in large swaths of the Indian subcontinent.

India’s freedom struggle was guided by the vision of Hindu nationalism and not by constitutional patriotism. The Congress brand of nationalism was but a subset of this broader Hindu nationalism with the Congress itself as the pre-eminent Hindu party. The Muslim question forced the Congress to adopt a more tempered language and symbolism later and to weave the myth of Hindu-Muslim unity. But it failed to prevent the Partition of India. The Congress was taken over by Left-leaning secular denialists under Jawaharlal Nehru who, instead of confronting reality, pretended it did not exist.

----------

Hindu nationalism has never been fringe; it is Nehruvian secularism that was the fringe. And with the fall of the old English-speaking elites, the system they created is also collapsing along with accompanying myths like Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb and Hindu-Muslim unity. The fact is that Hindus and Muslims lived together, but separately. And they share a violent and cataclysmic past with each other, which has never been put to rest.

Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb was an urban-feudal construct with no serious takers outside a limited circle. In villages, whatever unity existed was because the caste identities of both Hindu and Muslims dominated instead of religious identities or because Hindu converts to Islam maintained earlier customs and old social links with Hindus like common gotra and caste. But all that evaporated quickly with the Islamic revivalist movements such as the Tabligh and pan-Islamism from 19th century onwards. It never takes much for Hindu-Muslim riots to erupt. There was nothing surprising about the anti-Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) protests and widespread riots. As political communities, Hindus and Muslims have hardly ever agreed on the big questions of the day.

-----------

What we are witnessing today is twilight of the first Republic. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is but a modern vehicle of the historical process of the rise of the Hindu rashtra. In the north, Jammu and Kashmir is fully integrated. In the south, Dravidianism is melting away. In the east, Bengal is turning saffron. In the west, secular parties must ally with a local Hindutva party to survive.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on October 5, 2020 at 4:11pm

-

Jaswant Singh, India’s former foreign minister, who died on September 27 after six years in a coma from a fall at his home, was carrying a history-making sheaf of typed papers in his briefcase on July 16, 2001, in Agra, papers of immeasurable importance to the future history of South Asia.

https://scroll.in/article/974874/what-if-jaswant-singh-had-been-all...

So powerful were the contents in Jaswant Singh’s draft he had agreed with his Pakistan counterpart that it had the potential to forestall any future war between India and Pakistan. Singh’s far-right colleague and home minister LK Advani torpedoed the draft pact moments before Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Pervez Musharraf were to accept it.

The sabotaged Agra summit could have saved India and Pakistan an endless need to procure military hardware at prohibitive costs to their poverty-stricken masses. Had history not played truant that day in Agra, there would be a hoard of money available for healthcare and education for both countries – saved from scandal-tainted Rafale jets in India, for example – which in turn would have enabled both to better fight the coronavirus menace, and perhaps even spare precious resources for the less endowed neighbours.

The French Rafales were meant to deal with the military contingency in Ladakh with China, one might argue. Yes and no. Jaswant Singh’s peace deal carried the power, in fact, to vacate the need for even India and China to think of war or to send hapless men to inhospitable climes for guarding their ill-defined frontiers. There would be perhaps no deaths from frostbite or avalanches in Siachen either. There would be no need to interdict the Karakoram Highway.

There is a humanitarian catastrophe brewing in Jammu and Kashmir. An Agra pact would have made unnecessary the subjugation of Jammu and Kashmir last year. True, there were howls of protest from Hindutva nationalists when Jaswant Singh proposed in a subsequent TV interview that India could accept the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir as a hard border and thus end a core dispute with Pakistan.

The protests had less to do with the logic of peace between nuclear rivals, rather they were needed by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and its assiduously nurtured hatred for Pakistan. A worried Arun Jaitley, the late partisan of the RSS, told the Americans in as many words, according to WikiLeaks, that good relations with Pakistan were detrimental to Hindutva’s political constituency in northern India. The instructive core of such an argument can imply that the December 2001 terror attack on the Indian parliament or the November 2008 terror attack in Mumbai harmed India but helped the BJP. The logic again came into play with the Pulwama attack last year.

To loosely translate an Indian saying, the horse cannot befriend the grass. That is a likelier reason for the failure of the Agra summit – because peace with Pakistan would destroy the BJP’s plank to win votes. It goes to the credit of Vajpayee and Jaswant Singh that they did not see their politics through the prism of perpetual communal hostility.

Comment

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Pakistani Student Enrollment in US Universities Hits All Time High

Pakistani student enrollment in America's institutions of higher learning rose 16% last year, outpacing the record 12% growth in the number of international students hosted by the country. This puts Pakistan among eight sources in the top 20 countries with the largest increases in US enrollment. India saw the biggest increase at 35%, followed by Ghana 32%, Bangladesh and…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on April 1, 2024 at 5:00pm

Agriculture, Caste, Religion and Happiness in South Asia

Pakistan's agriculture sector GDP grew at a rate of 5.2% in the October-December 2023 quarter, according to the government figures. This is a rare bright spot in the overall national economy that showed just 1% growth during the quarter. Strong performance of the farm sector gives the much needed boost for about …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on March 29, 2024 at 8:00pm

© 2024 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network