PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

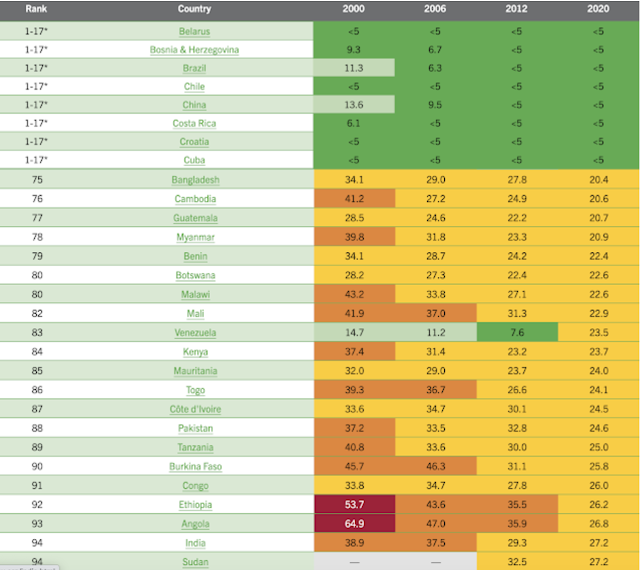

India ranks 94th among 107 nations ranked by World Hunger Index in 2020. Other South Asian have fared better: Pakistan (88), Nepal (73), Bangladesh (75), Sri Lanka (64) and Myanmar (78) – and only Afghanistan has fared worse at 99th place. The COVID19 pandemic has worsened India's hunger and malnutrition. Tens of thousands of Indian children were forced to go to sleep on an empty stomach as the daily wage workers lost their livelihood and Prime Minister Narendra Modi imposed one of the strictest lockdowns in the South Asian nation. Pakistan's Prime Minister Imran Khan opted for "smart lockdown" that reduced the impact on daily wage earners. China, the place where COVID19 virus first emerged, is among 17 countries with the lowest level of hunger.

|

| World Hunger Rankings 2020. Source: World Hunger Index Report |

Hunger and malnutrition are worsening in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia because of the coronavirus pandemic, especially in low-income communities or those already stricken by continued conflict.

|

| Global Epicenters of Covid19. Source: Bloomberg |

Global food prices are soaring by double digits amid the coronavirus pandemic, according to Bloomberg News. Bloomberg Agriculture Subindex, a measure of key farm goods futures contracts, is up almost 20% since June. It may in part be driven by speculators in the commodities markets. These rapid price rises are hitting the people in Pakistan and the rest of the world hard. In spite of these hikes, Pakistan remains among the least expensive places for food, according recent studies. It is important for Pakistan's federal and provincial governments to rise up to the challenge and relieve the pain inflicted on the average Pakistani consumer.

| Global Agricultural Futures Contracts. Source: Bloomberg |

Global Food Prices:

Global food prices are increasing at least partly due to several nations buying basic food commodities to boost their strategic reserves in the midst of the pandemic. A Bloomberg News report says that "agricultural commodity buyers from Cairo to Islamabad have been on a shopping spree since the Covid-19 pandemic upended supply chains". It may in part be driven by speculators in the commodities markets. Here's an excerpt of the Bloomberg story:

"Agricultural prices have been on the rise as countries stepped up purchases, adding to demand from China and a drought in the Black Sea region. That has helped push the Bloomberg Agriculture Subindex, which measures key farm goods futures contracts, up almost 20% since June. Sugar prices have gained a boost as China replenished stockpiles, said Geovane Consul, chief executive officer of a Brazilian sugar and ethanol joint venture between U.S. agribusiness giant Bunge Ltd. and British oil major BP Plc."

Supply Constraint in Pakistan:

The Pakistan Government estimates final wheat production ended up at 25.5 million tons, slightly above the five-year average of 25.38 million tons, according to Grain Central. While that represented a 1.2 million tons increase on the 24.3 million tons harvested in 2019, it was well short of the government’s target of 27 million tons, forcing Pakistan to import wheat at higher global prices.

Demand for fruits and vegetables is also rising at about 9.5% a year, according to Mordor Intelligence. The supply is falling short of demand, putting pressure on prices.

|

| Global Food Price Comparison. Source: Bayut |

The food prices have risen 14% for urban and 16.8% for rural areas of Pakistan in the last 12 months, according to Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. In spite of this inflationary trend, the grocery prices in Pakistan remain among the lowest in the world. A comparison by Dubai-based Bayut shows that groceries in Pakistan cost 72.9% less than in the United States. Other least-expensive countries for groceries include Tunisia ( 67% less), Ukraine ( 66.7% less), Egypt (65.6% less) and Kosovo (65.6% less).

Globally, Switzerland sells the most expensive groceries, with prices 79.1% higher than in the U.S. Norway is the second most expensive place to buy groceries, with prices 37.4% more expensive than in the U.S., and Iceland is third most expensive, where food items are 36.6% pricier, according to Bayut.

|

| Cost of Dining Out. Source: Commodity.com |

Summary:

India ranks 94th among 107 nations ranked by World Hunger Index in 2020. China, the place where COVID19 virus first emerged, is among 17 countries with the lowest level of hunger. Other South Asian have fared better: Pakistan (88), Nepal (73), Bangladesh (75), Sri Lanka (64) and Myanmar (78) – and only Afghanistan has fared worse at 99th place. However, global food price hikes have also hit average Pakistani hard in spite of the fact that grocery prices in Pakistan remain the lowest the world. Bloomberg Agriculture Subindex, a measure of key farm goods futures contracts, is up almost 20% since June. It may in part be driven by speculators in the commodities markets. World food commodity prices are increasing at least partly due to several nations buying basic food commodities to boost their strategic reserves in the midst of the pandemic. It is important for Pakistan's federal and provincial governments to intervene in the markets to relieve the average Pakistani consumer's pain.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

COVID19 in Pakistan: Test Positivity Rate and Deaths Declining

Construction Industry in Pakistan

Pakistan's Pharma Industry Among World's Fastest Growing

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

Is Pakistan's Response to COVID19 Flawed?

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid19 Crisis

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Coronavirus Antibodies Testing in Pakistan

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan Fares Marginally Better Than India On Disease Burdens

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

Democracy vs Dictatorship in Pakistan

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

Panama Leaks in Pakistan

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

Riaz Haq

"Soaring prices of agricultural products are stoking food-security jitters in China. According to the China’s National Bureau of Statistics, food prices went up by 13 percent in July, compared to the previous July; the price of pork rose about 85 percent. On a year-on-year basis, food prices have increased by 10 percent in 2020 — the price of corn is 20 percent higher and the price of soybeans, 30 percent"

https://thehill.com/opinion/international/516607-another-famine-com...

Oct 17, 2020

Riaz Haq

Global #food prices rise as countries stockpile amid worsening #coronavirus #pandemic. In times of uncertainty, people are more likely to hoard. Countries importing grains to boost their pandemic stockpiles include #China, #Egypt, #Jordan, #Taiwan, others. https://www.marketplace.org/2020/10/16/global-food-prices-rise-coun...

A number of countries, including China, are stockpiling for an uncertain pandemic season amid concerns over whether the global supply chain for food can remain intact as COVID-19 cases rise worldwide.

World food prices have been rising for four straight months, according to a United Nations price index. Countries importing grains to boost their pandemic stockpiles include Egypt, Jordan, Taiwan and others.

“China comes to mind, as they’ve taken on a massive restocking program,” said Michael Magdovitz, food and agriculture analyst at Rabobank. “But also India. Countries may increase their buffers to avoid any supply-side issues,” such as lockdowns or border closures should the pandemic worsen.

“I think people are trying to protect their own interests, which in some ways is rational,” Preston said. “Even if it can cause what they call a ‘commons problem,’ where then there’s not enough for everybody.”

When the pandemic first hit, governments and food security authorities expressed concerns about food protectionism. That didn’t come to pass globally.

Still, bottlenecks have turned up in developing countries. In South Africa, workers were banned from traveling to a packing plant for citrus, said Thomas Reardon, agricultural economist at Michigan State University.

“Also, because wood was not classed as an essential item, the wood was not coming in to make packing crates, so the fruit could not be packed,” Reardon said.

Globally, the prices of grain and meat continue to rise, just as more and more people can’t afford them given widespread job losses. Sherman Robinson, trade scholar at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, said food insecurity is showing up everywhere.

“It’s widespread across developing countries,” Robinson said. “In the developed countries, it really depends on how good your social safety net is. So in the U.S. case, we’re probably among the worst of the developed countries.”

Oct 17, 2020

Riaz Haq

#India ranks among the world’s worst in terms of #coronavirus, religious bigotry, #humanrights, #hunger, #happiness, #water quality, #AirQuality, #media #freedom, #environment etc. #Modi #BJP #Hindutva

https://twitter.com/aneraokailash/status/1317474161363546115?s=21

Kailash Anerao

@AneraoKailash

India:

94 out of 107-Global Hunger Index

147 out of 157-Oxfam Inequality Index

120 out of 122-Water Quality Index

179 out of 180-Air Quality Index

144 out of 156-UN World Happiness Index

140 out of 180-World Press Freedom Index

167 out of 180-Environmental Performance Index

@hrw

Oct 17, 2020

Riaz Haq

OXFAM #Inequality Index: #India's #Health Budget Is 4th Lowest In The World; Worse Than #Pakistan, #Nepal Amidst #COVID19 #Pandemic. @trakintech https://trak.in/tags/business/2020/10/13/shocking-indias-health-bud...

https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/fighting-inequality-time-covid-19...

According to the latest ‘Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index 2020’, report published by the international charity confederation Oxfam on

7 October 2020 , India ranked 155th in a survey consisting of 158 countries, showing that the country spends less than 4% of its budget on health.

The health spending index of India is so poor that even its neighbouring countries like Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh spend slightly more than 4% of their budget on health.

As per Oxfam’s latest 2020 Index report, of the 158 countries surveyed for checking whether they allocate 15% of their respective budgets on health as recommended, it was found that Nigeria, Bahrain and India were among the lowest rankers, in terms of health spending index.

India secured the 155th spot, sharing its position with Afghanistan, both of which allocated less than 4% of their budget on health.

Speaking of health spending indices, Oxham found that only 28 of these 158 surveyed countries were spending the recommended fraction of 15% of their budgets on health.

The report said, “India’s health budget is the fourth lowest in the world. Just half of its population have access to even the most essential health services”.

The report also mentioned that while the trend of allocating a very small percentage of budget towards health is persistent across South Asian countries,

Pakistan spent a little over 4% of its budget on health, while

Nepal and Bangladesh spent 5%.

The report reads,

“This is particularly damaging when just half of India’s population (55%) has access to even the most essential services, and more than 70% of health spending is being met from household budgets.”

Also, as per the database from the World Bank, in 2017 India dedicated only 3.4% of its expenditure towards health.

Just to get an understanding of comparison, in the same year Japan spent 23.6% of the government budget on health.

Oct 17, 2020

Riaz Haq

WHICH COUNTRY IS DOING THE MOST TO FIGHT INEQUALITY? by OXFAM

A global ranking of governments based on what they are doing to tackle the gap between rich and poor

http://www.inequalityindex.org/

The Overall Index Score combines all three core pillars on which the index is based: social spending, progressive taxation policies and labour rights.

Pakistan ranks 128 among 158 countries. India ranks 129 & Bangladesh 113.

Oct 17, 2020

Riaz Haq

#India in denial. India is neither comparable to the traditional superpower, #US, nor to an emerging superpower, #China...not even equivalent to its immediate neighbors #Bangladesh, #Pakistan, #SriLanka, #Nepal in many development indicators. - Asia Times https://asiatimes.com/2020/10/india-is-nowhere-in-the-world-denial-...

The elite in New Delhi delude themselves by thinking the country can hold its own on the world stage

By BHIM BHURTEL

OCTOBER 20, 2020

Despite Indian strategists’ claim that India is an aspirant global power, it is at the bottom in South Asia except for war-torn Afghanistan in the GHI ranking.

The report suggests that India ranks 94th out of 104 countries listed. India shares the same rank as Sudan, in the red zone. That means India’s hunger situation is in the “alarming” category. India’s South Asian peers rank as follows: Sri Lanka 64, Nepal 73, Bangladesh 75, and Pakistan 88.

---------

The perceptions of Indian political leaders and top bureaucrats about their country’s position in the world appear far removed from reality.

These elites appear not to be mindful of the republic’s fundamental purposes envisaged in the constitution. And they seem lost to their duty and function to the people.

Yet they want to attempt a massive task that is beyond their economic, technological, political, military and strategic capacity.

----------

India is unable to feed its kids and yet dreams of being a global strategic player.

Second, I read a report by Andy Mukherjee in Bloomberg Business dated October 17. The headline is fascinating: “The next China? India must first beat Bangladesh.”

Mukherjee writes: “Ever since it began opening up the economy in the 1990s, India’s dream has been to emulate China’s rapid expansion. After three decades of persevering with that campaign, slipping behind Bangladesh hurts its global image. The West wants a meaningful counterweight to China, but that partnership will be predicated on India not getting stuck in a lower-middle-income trap.”

The third report I skimmed was published earlier but is still relevant. The Davos-based World Economic Forum (WEF) started to publish the World Inclusive Development Report (IDI) in 2017.

The WEF says IDI is designed as an alternative to GDP and reflects more closely the criteria by which people evaluate their countries’ economic progress. The IDI 2018 ranking suggested that India is again at the bottom. In the IDI ranking of 74 states in the Emerging Economies category, Nepal ranks No 22, Bangladesh 34, Sri Lanka 40, Pakistan 47, and India 62.

Besides, India, the world’s largest functional democracy, is not a role model for other countries in South Asia, even for its human-rights record. Amnesty International’s recent closure of its operations in India confirms this.

These reports show that India is neither comparable to the traditional superpower, the US, nor to an emerging superpower, China. It is also not equal to a middle-power country like Japan or Germany. It is not even equivalent to its immediate neighbors Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Nepal in many development indicators.

India lags its South Asian peers. Therefore, India is not a role model in the South Asia region, either in economic performance or in socioeconomic development. Recently, South Asian countries have been looking to China with hope rather than India because of India’s poor image. A country with a lower socioeconomic development ranking cannot be a role model for higher-ranked countries.

Indian leaders’ and bureaucrats’ denials won’t work for India. The sooner India accepts that it lags far behind superpowers, middle-power countries and its immediate neighbors, the sooner it will start fixing its economy.

Hubris of being a global player may be useful for Indian leaders and officials but it won’t help the people.

Oct 20, 2020

Riaz Haq

Dirty air: how #India became the most polluted country on earth. World's 10 dirtiest cities are all in India. #pollution #disease #China #Pakistan #Asia https://ig.ft.com/india-pollution/

https://twitter.com/haqsmusings/status/1319724406747246592?s=20

The problem is most acute in India but it is not alone. The Financial Times collated Nasa satellite data of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) — a measure of air quality — and mapped it against population density data from the European Commission to develop a global overview of the number of people affected by this type of dangerous pollution.

The results are alarming: not just the number of people breathing in polluted air, but those breathing air contaminated with particulates that are multiple times over the level deemed safe — 10 micrograms of PM2.5 per cubic metre — by the World Health Organisation.

The data show that more than 4.2bn people in Asia are breathing air many times dirtier than the WHO safe limit. It only takes into account areas that are populated to avoid skewing the numbers for countries such as China and Russia that have vast unpopulated regions.

Historically China has grabbed most headlines for poor air quality. But as the time-lapse video of PM2.5 pollution between 1998 and 2016 shows, India is now in a far worse state than its larger neighbour ever was.

The 2016 data, the latest available, show that, although both countries have a similar number of people breathing air above the safe limit, India has far more people living in heavily polluted areas. At least 140m people in India are breathing air 10 times or more over the WHO safe limit.

A study published in The Lancet has estimated that in 2017 air pollution killed 1.24m Indians — half of them younger than 70, which lowers the country’s average life expectancy by 1.7 years. The 10 most polluted cities in the world are all in northern India.

Top officials in prime minister Narendra Modi’s government have suggested New Delhi’s air is little dirtier than that in other major capitals such as London.

Harsh Vardhan, India’s environment minister and a doctor, has played down the health consequences of dirty air, insisting it is mainly a concern for those with pre-existing lung conditions. But that appears to fly in the face of international studies that show that air pollution has a wide-ranging impact, including an elevated risk for heart attacks and strokes, increased risk of asthma, reduced foetal growth, stunted development of children’s lungs, and cognitive impairment.

Dr Vardhan has claimed India needed its own research to determine whether dirty air is really harmful to otherwise healthy people — an argument the government also made in the Supreme Court.

Dr Kumar believes New Delhi’s unwillingness to acknowledge the severity of its pollution crisis stems from its reluctance to take strong measures tackle large polluters. Such a crackdown would inevitably upset powerful vested interests in the automotive sector, highly polluting small and medium-sized industries, power plants, construction companies and farmers. And it could hit economic growth ahead of elections next year.

“They are not unaware but, despite being aware, they deny,” says Dr Kumar, “The corrective measures that would be needed are unpleasant, and might make them lose votes rather than gain votes.”

But environmentalist Sunita Narain, director-general of New Delhi’s Centre for Science and Environment, says official attitudes have shifted since last winter’s catastrophic air emergency, when record pollution levels forced schools to close for several days.

“That was a turning point,” says Ms Narain, who has battled India’s air pollution for decades. “There is outrage now against pollution — it is also now much more of a middle-class issue and government is acting because it understands the public health emergency.”

Oct 23, 2020

Riaz Haq

#COVID19 #pandemic has created a 2nd crisis in #India — the rise of child trafficking. #Lockdown meant millions of children deprived of the midday meal they used to receive at school and many people lost their jobs. #Hunger #poverty #Modi #BJP #coronavirus https://www.cnn.com/2020/10/24/asia/india-covid-child-trafficking-i...

One evening in August, a 14-year-old boy snuck out of his home and boarded a private bus to travel from his village in Bihar to Jaipur, a chaotic, crowded and historical city 800 miles away in India's Rajasthan state.

He and his friends had been given 500 rupees (about $7) by a man in their village to "go on vacation" in Jaipur, said the boy, who CNN is calling Mujeeb because Indian law forbids naming suspected victims of child trafficking.

As the bus entered Jaipur, it was intercepted by police.

The man was arrested and charged under India's child trafficking laws, along with two other suspects. Nineteen children, including Mujeeb, were rescued. Jaipur police said they were likely being taken to bangle factories to be sold as cheap labor.

In India, children are allowed to work from the age of 14, but only in family-related businesses and never in hazardous conditions. But the country's economy has been hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic and many have lost their jobs, leading some families to allow their children to work to bring in anything they can.

Making colored lac bangles like those sold in Jaipur is hot and dangerous work, requiring the manipulation of lacquer melted over burning coal. Bangle manufacturing is on the list of industries that aren't allowed to employ children under 18.

"Children have never faced such crisis," said 2014 Nobel Peace Prize winner Kailash Satyarthi, whose organization Bachpan Bachao Andolan (Save the Childhood Movement) works to protect vulnerable children. "This is not simply the health crisis or economic crisis. This is the crisis of justice, of humanity, of childhood, of the future of an entire generation."

When India went into a strict lockdown in March, schools and workplaces closed. Millions of children were deprived of the midday meal they used to receive at school and many people lost their jobs.

Traffickers have exploited the situation by targeting desperate families, activists said.

Between April and September, 1,127 children suspected of being trafficked were rescued across India and 86 alleged traffickers were arrested, according to Bachpan Bachao Andolan.

Most of the children came from rural areas of poorer states, such as Jharkhand or Bihar. Pramila Kumari, the chairwoman of Bihar's Commission For Protection Of Child Rights, said the government commission had received more complaints of trafficking during the pandemic.

Child trafficking, when young people are tricked, forced or persuaded to leave their homes and then exploited, forced to work or sold, can occur in several ways. Experts say sometimes, children are lured with false promises without their parents ever knowing, like Mujeeb. Other times, desperate parents hand their children over to work so they can send money home.

Oct 24, 2020

Riaz Haq

#US green card: Over 8,00,000 #Indian nationals in green card backlog in #UnitedStates . With 8 decades wait, 200,000 will die before reaching the front of the line - The Economic Times

https://m.economictimes.com/nri/visa-and-immigration/over-800000-in...

-------------------------

About 68 percent of the employment-based backlog was from India in April 2020. This outcome is the result of country caps that limit nationals of any single birthplace to no more than 7 percent of the green cards in a year unless the green cards would otherwise go unused. Another 14 percent was from China, and 18 percent from the rest of the world. The Chinese backlog actually declined slightly during 2020 through April, but the backlogs for Indians and all other applicants grew significantly.

https://www.cato.org/blog/employment-based-green-card-backlog-hits-...

Nov 22, 2020

Riaz Haq

#Hunger pangs in #Modi's #India have just gotten worse. The proportion of children under 5 who are underweight has risen, compared to the prior National Family Health Survey (NFHS) round in 2015-16. India ranks worse than #Pakistan, #Bangladesh and #Nepal. https://www.livemint.com/news/india/hunger-pangs-in-india-may-have-...

One of the mysteries associated with India’s rapid economic expansion over the past three decades is the persistence of hunger and malnutrition, especially among children. A recent survey shows the country may be slipping further, instead of improving. Mint explains.

What do the NFHS findings indicate?

In a number of large states, the proportion of children under 5 who are underweight has risen, compared to the previous National Family Health Survey (NFHS) round in 2015-16. Even relatively advanced states like Gujarat and Maharashtra have recorded a slide in the nutritional well-being of their children since 2015. This is contradictory to what should ideally happen in a growing economy, since rising prosperity should improve access to food. The ground situation in 22 states and union territories was captured in phase-I of the survey—which was interrupted by the pandemic and the subsequent lockdown.

Could this be a fallout of the pandemic?

The NFHS surveyors had started fanning out to households across the country since mid-2019. The exercise of reaching out to over 600,000 households was likely to last a year, but those plans were disrupted in March. Thus, the phase-I results have nothing to do with covid-19 and are an indication of India’s nutritional state before March. If anything, the prevalence of hunger is only expected to have shot up in subsequent months. The first official glimpse of covid’s economic impact may, thus, get captured in phase-II, which will cover key states like Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. The results will be out by May 2021.

-------------

India has been a poor performer in global hunger indices, often ranking behind even poorer Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal. But it has at least managed to show improvements over its own past record. 2020 may be an outlier when even this kind of progress might not happen. A 2017-18 consumption survey by the National Statistical Office had shown a steep drop in monthly per capita consumption in rural India. NFHS-5 indicates economic woes were real in late-2019 and in early 2020 too, even before covid.

Dec 14, 2020

Riaz Haq

#Covid is creating a #hunger catastrophe in #India: In the 2020 Global Hunger Index, India ranks 94th out of 107 countries. The #pandemic and resulting unemployment has made India’s hunger crisis worse. #coronavirus #BJP #Modi #Hindutva https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/06/covid-19-pandemic-hunger-cat...

COVID-19 has exacerbated hunger and poverty worldwide, especially in India.

The crisis highlights the importance of putting relief directly into the hands of vulnerable people.

Solutions must address both immediate food insecurity and provide livelihood opportunities so as to break the cycle of hunger and poverty.

COVID-19 has proven to be not only a health crisis, but also a livelihood crisis – quickly turning into a hunger and malnutrition catastrophe.

The pandemic has led to increase in global food insecurity, affecting vulnerable households in almost every country. It has exacerbated existing inequalities, pushing millions of people into the vicious cycles of economic stagnation, loss of livelihood and worsening food insecurity.

Global hunger fell for decades, but it's rising again

The World Bank estimates that 71 million people will be pushed into extreme poverty across the globe as a result of the pandemic. The World Food Programme estimates that an additional 130 million people could fall into the category of “food insecure” over and above the 820 million who were classified as such by the 2019 State of Food Insecurity in the World Report.

As the deadly second wave ravages India, individual states have imposed lockdowns and strict restrictions to curb the spread of the virus. During the first phase, the plight and misery of the migrant workers and other vulnerable communities was laid bare. But this time, the health crisis has overwhelmed the existing livelihood and hunger crisis which still looms large in most of our towns and villages.

The CMIE Unemployment Data reveals a grim picture, with rural unemployment spiralling to 14.34% and urban unemployment reaching 14.71% as of 16 May 2021. In a country where a majority of the workforce is in informal sector, people have been massively affected due to loss of jobs and the lack of access to the benefits (including social security) that come with formal employment. The daily wagers, construction workers, street vendors and domestic helpers have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic and lockdowns and are living a life of uncertainty and disrupted incomes. Agriculture is the primary occupation in the villages, but due to frequent lockdowns, there has been a disruption of supply chains and access to market for the sale of agricultural produce, impacting the income of rural households. And while there is no gender-disaggregated data on the impact of COVID-19 specifically on women, experience shows women are disproportionately affected during pandemics, economic downturns and times of food insecurity.

In the 2020 Global Hunger Index, India ranks 94th out of 107 countries. The pandemic and resulting unemployment has made India’s hunger crisis worse. The First Phase of the National Family Health Survey (2019-2020) has revealed alarming findings, with as many as 16 states showing an increase in underweight and severely wasted children of under the age of 5. The pandemic is becoming a nutrition crisis, due to overburdened healthcare systems, disrupted food patterns and income loss, along with the disruption of programmes like the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) and the mid-day meal.

Jul 21, 2021

Riaz Haq

Global #HungerIndex 2021: #Superpower #India slips to 101st spot, behind #Pakistan, #Bangladesh, #Nepal. Only 15 countries, like Papua New Guinea (102), #Afghanistan (103), #Nigeria (103), #Congo (105), fared worse than #Modi's India this year. #GHI2021 https://indianexpress.com/article/india/global-hunger-index-2021-in...

India has slipped to the 101st position among 116 countries in the Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2021 from its 2020 ranking (94), to be placed behind Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal.

With this, only 15 countries — Papua New Guinea (102), Afghanistan (103), Nigeria (103), Congo (105), Mozambique (106), Sierra Leone (106), Timor-Leste (108), Haiti (109), Liberia (110), Madagascar (111), Democratic Republic of Congo (112), Chad (113), Central African Republic (114), Yemen (115) and Somalia (116) — fared worse than India this year.

A total of 18 countries, including China, Kuwait and Brazil, shared the top rank with GHI score of less than five, the GHI website that tracks hunger and malnutrition across countries said on Thursday.

The report, prepared jointly by Irish aid agency Concern Worldwide and German organisation Welt Hunger Hilfe, mentioned the level of hunger in India as “alarming” with its GHI score decelerating from 38.8 in 2000 to the range of 28.8 – 27.5 between 2012 and 2021.

The GHI score is calculated on four indicators — undernourishment; child wasting (the share of children under the age of five who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition); child stunting (children under the age of five who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition); child mortality (the mortality rate of children under the age of five).

According to the report, the share of wasting among children in India rose from 17.1 per cent between 1998-2002 to 17.3 per cent between 2016-2020, “People have been severely hit by COVID-19 and by pandemic related restrictions in India, the country with highest child wasting rate worldwide,” the report said.

Neighbouring countries like Nepal (76), Bangladesh (76), Myanmar (71) and Pakistan (92), which are still ahead of India at feeding its citizens, are also in the ‘alarming’ hunger category.

However, India has shown improvement in indicators like the under-5 mortality rate, prevalence of stunting among children and prevalence of undernourishment owing to inadequate food, the report said.

Stating that the fight against hunger is dangerously off track, the report said based on the current GHI projections, the world as a whole — and 47 countries in particular — will fail to achieve even a low level of hunger by 2030.

“Although GHI scores show that global hunger has been on the decline since 2000, progress is slowing. While the GHI score for the world fell 4.7 points, from 25.1 to 20.4, between 2006 and 2012, it has fallen just 2.5 points since 2012. After decades of decline, the global prevalence of undernourishment — one of the four indicators used to calculate GHI scores — is increasing. This shift may be a harbinger of reversals in other measures of hunger,” the report said.

Food security is under assault on multiple fronts, the report said, adding that worsening conflict, weather extremes associated with global climate change, and the economic and health challenges associated with Covid-19 are all driving hunger.

“Inequality — between regions, countries, districts, and communities — is pervasive and, (if) left unchecked, will keep the world from achieving the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) mandate to “leave no one behind,” it said.

Oct 14, 2021

Riaz Haq

Global Hunger Index

2000 India 38.8 Pakistan 36.7

2008 India 37.4 Pakistan 33.1

2012 India 28.8 Pakistan 32.1

2020 India 27.2 Pakistan 24.6

2021 India 27.5 Pakistan 24.7

https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2021%20GH...

Oct 14, 2021

Riaz Haq

A Dire Hunger Situation amid Multiple Crises The 2021 Global Hunger Index (GHI) points to a grim hunger situation fueled by a toxic cocktail of the climate crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and increasingly severe and protracted violent conflicts. Progress toward Zero Hunger by 2030, already far too slow, is showing signs of stagnating or even being reversed.

The prevalence of undernourishment is not regularly calculated at the subnational level, but nascent efforts to do so have begun and reveal subnational variation. In Pakistan, for example, the 2018–2019 rates ranged from 12.7 percent undernourished in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province to 21.5 percent in Punjab (Afridi et al. 2021).

https://reliefweb.int/report/world/2021-global-hunger-index-hunger-...

Oct 14, 2021

Riaz Haq

#Modi Announces Goal To Make #India, World's Strongest #Military Power In 'Aatmnirbhar' Way. This news came on the same say that #India slipped 7 places to 101 on Global #HungerIndex, behind #Bangladesh, #Nepal & #Pakistan. #GlobalHungerIndex2021 https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/india-news-goal-to-make-...

Prime Minister Narendra Modi while addressing the event of the launch of seven state-run defence companies on the occasion of Vijaydashmi, said that he wants to robust India's defence capabilities in an 'Aatmnirbhar' way.

On the occasion of Vijaydashmi, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched seven state run defence companies.

The government passed an order on 16th June to convert Ordnance Factory Board from a Government Department into seven 100% Government owned corporate entities.

The Prime Minster said, "India is taking new resolutions to build new future. Today, there is more transparency & trust in defence sector than ever before."

Stressing on the need for aatmnirbhar bharat, he said, "Under the aatmnirbhar bharat scheme, our goal is to make country world's biggest military power on its own.

He said that major reforms have been rolled out in defence sector; instead of the conventional stagnant policies, the single window system has been arranged now.

"After Independence, there was a need to upgrade ordnance factories, adopt new-age technologies, but it didn't get much attention," the Prime Minister said.

The Prime Minsiter's office informed that the new strategy for defence production will focus on, 'Import substitution, diversification, newer opportunities and exports'.

Defence Minister Rajnath Singh and representatives from the defence industry associations were present in the event.

The Government of India has decided to convert Ordnance Factory Board from a Government Department into seven 100% Government owned corporate entities, as a measure to improve 'self-reliance in the defence preparedness of the country'. This move will bring about enhanced functional autonomy, efficiency and will unleash new growth potential and innovation, the Prime Minister's Office released a video informing about it.

Rs. 65,000 Crore have been moved from the Ordinance Factory Board and allotted to these 7 companies, the video added.

Oct 15, 2021

Riaz Haq

From Pakistan to Somalia to Cameroon, Action Against Hunger has established Farmer Field Schools. Our agriculture experts teach farmers climate-smart growing techniques, introduce nutritious, resilient crops, and provide practice plots for people to test what they’ve learned. When participants are ready, they take supplies and new skills home to their own land.

https://reliefweb.int/report/world/10-ways-were-helping-families-ta...

--------

In Pakistan, for example, we’re introducing crops like sugar beets, which can help reduce saline levels in soil – a consequence of drought and rising tides. Around the world, our teams are also working with farmers to teach practices that encourage more fertile fields, such as composting.

GROWING CROPS WITH LESS WATER

Even when rainfall is limited, it’s possible for gardens to flourish and provide enough yield to feed families and livestock. By teaching innovative growing techniques – including hydroponics and vertical gardens – our teams are helping farmers grow crops with less water.

ESTABLISHING LOCALLY-LED FARMER COOPERATIVES

Tackling climate change is a team effort. To foster collaboration and learning, Action Against Hunger creates and supports farmers’ cooperatives. Some of these groups come together to collectively rent land for farming, while others share lessons learned with each other. In Uganda, many farmers’ groups are negotiating fair prices for supplies and creating local demand for nutritious crops like mushrooms.

HARNESSING THE POWER OF THE SUN

During a drought or a heatwave, the sun beats down on rural communities. So, with the help of solar power, we’re putting that sunshine to good use. Now, across many of the countries where we work, the sun helps to fuel everything from water pumps to portable irrigation systems.

OPTIMIZING LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES

Around the world, Action Against Hunger uses agroecological principles to sustainably improve food security in vulnerable communities. What exactly does that mean? Agroecology is an environmentally-friendly approach that helps people make the most of their local natural resources – including land, water, soil, and seeds - to grow nutritious foods, diversify their crops, and build up markets.

PROVIDING A HELPING HAND IN TOUGH TIMES

Our programs aim to help communities to build their resilience to shocks – but, sometimes, a shock is too severe or sudden for people to cope. That’s why our teams also provide cash transfers in emergencies. For a family displaced by floods, money is often the fastest and most flexible way to help them find food, a place to stay, medicine, and other basic things they need to survive.

MAKING FOOD LAST THROUGH LEAN SEASONS

Each year, many rural communities prepare to face the “hunger season,” or the period between harvests when food supplies run out. Climate change has exacerbated hunger seasons: prolonged droughts and other severe shocks have made hunger seasons longer and more unpredictable. To support families, we’re helping them make their crops last longer with drying and storage tools.

Oct 16, 2021

Riaz Haq

#Food Security Index: #India at 71st spot out of 113 nations. #Pakistan (with 52.6 points) scored better than India (50.2 points) in the category of food affordability. #FoodSecurity #SouthAsia https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/nation/food-security-index-india-at-71st-spot-out-of-113-nations-326660#.YW708XmUcCo.tw...

New Delhi, October 19

India is ranked at 71st position in the Global Food Security (GFS) Index 2021 of 113 countries, but the country lags behind its neighbours Pakistan and Sri Lanka in terms food affordability, according to a report.

Pakistan (with 52.6 points) scored better than India (50.2 points) in the category of food affordability. Sri Lanka was even better with 62.9 points in this category on the GFS Index 2021, a global report released by Economist Impact and Corteva Agriscience on Tuesday said.

Ireland, Australia, the UK, Finland, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Canada, Japan, France and the US shared the top rank with the overall GFS score in the range of 77.8 and 80 points on the index.

The GFS Index was designed and constructed by London-based Economist Impact and is sponsored by Corteva Agriscience.

The GFS Index measures the underlying drivers of food security in 113 countries, based on the factors of affordability, availability, quality and safety, and natural resources and resilience. It considers 58 unique food security indicators including income and economic inequality – calling attention to systemic gaps and actions needed to accelerate progress toward United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of Zero Hunger by 2030.

According to the report, India held 71st position with an overall score of 57.2 points on the GFS Index 2021 of 113 countries, fared better than Pakistan (75th position), Sri Lanka (77th Position), Nepal (79th position) and Bangladesh (84th position). But the country was way behind China (34th position).

In the food affordability category, Pakistan (with 52.6 points) scored better than India (50.2 points). Sri Lanka was also better at 62.9 points on the GFS Index 2021.

https://impact.economist.com/sustainability/project/food-security-index/index

Oct 19, 2021

Riaz Haq

India asked Washington not to bring up China’s border transgressions: Former US ambassador

Kenneth Juster made the statement on a Times Now show when asked why the United States had not made any statement about Beijing’s aggression.

https://scroll.in/latest/1018580/india-asked-washington-not-to-ment...

India and China have been locked in a border standoff since troops of both countries clashed in eastern Ladakh along the Line of Actual Control in June 2020. Twenty Indian soldiers were killed in the hand-to-hand combat. While China had acknowledged casualties early, it did not disclose details till February 2021, when it said four of its soldiers had died.

After several rounds of talks, India and China had last year disengaged from Pangong Tso Lake in February and from Gogra, eastern Ladakh, in August.

Juster, who was the envoy to India between 2017 and 2021, had said in January 2021 that Washington closely coordinated with Delhi amid its standoff with Beijing, but left it to India to provide details of the cooperation.

----------

Former United States Ambassador to India Kenneth Juster has said that Delhi did not want Washington to mention China’s border aggression in its statements.

“The restraint in mentioning China in any US-India communication or any Quad communication comes from India which is very concerned about not poking China in the eye,” Juster said on a Times Now show.

The statement came in response to news anchor and Times Now Editor-in-Chief Rahul Shivshankar’s queries on whether the US had made any statements about Beijing’s aggression.

------------

During the TV show, defence analyst Derek Grossman claimed that Moscow was not a “friend” of India, saying that Russian President Vladimir Putin met his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping at the Beijing Olympics. Grossman told the news anchor that Putin and Xi had then said that their friendship had “no limits”.

He claimed that India’s strategy to leverage Russia against China did not have any effects. “In fact, Russia-China relations have gotten only stronger.”

To this, Shivshankar said that before passing any judgement on India and Russia’s relationship, he must ask if US President Joe Biden had condemned China’s aggression at the borders along the Line of Actual Control or mentioned Beijing in a joint statement with Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Grossman said: “To my understanding, the US has asked India if it wanted us to do something on the LAC but India said no – that it was something that India can handle on its own.”

Juster then backed Grossman’s contention.

Jun 17, 2022

Riaz Haq

#Indian Prime Minister Narendra #Modi boldly declared that his country was ready to “feed the world” after #Russia’s invasion of #Ukraine. Less than four months later, #India wants to import #wheat. #food #inflation #hunger #BJP #Hindutva #Islamophobia https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-08-21/india-may-import...

https://twitter.com/haqsmusings/status/1561361966572007425?s=20&...

Indications that a bumper wheat harvest wasn’t going to eventuate prompted the government to restrict exports in mid-May. State reserves have declined in August to the lowest level for the month in 14 years, according to Food Corp. of India, while consumer wheat inflation is running at close to 12%.

Indications that a bumper wheat harvest wasn’t going to eventuate prompted the government to restrict exports in mid-May. State reserves have declined in August to the lowest level for the month in 14 years, according to Food Corp. of India, while consumer wheat inflation is running at close to 12%.

The finance ministry didn’t respond to an email seeking comment. A spokesperson for the food and commerce ministries declined to comment. The food department on Sunday said in a Twitter post there was no “plan to import wheat” and the country has sufficient stocks to meet its requirements.

“Given a lot of the war risk premium has come off from global wheat prices, India can look at augmenting its domestic wheat supply via more imports,” said Sonal Varma, an economist at Nomura Holdings Inc. “However, since domestic wholesale wheat prices are lower than global prices, a reduction in import duties will also be essential to make it a viable option.”

Wheat spiked to near $14 a bushel in Chicago in early March as the war in Europe threatened a major source of global exports. Prices have now given up all of those gains as supply fears ease. They’re back below $8, alleviating some of the pressure on developing economies struggling to feed their people.

Despite being the world’s second-biggest wheat grower, India has never been a major exporter. It also never imported much, with overseas purchases at about 0.02% of production annually. The country was pretty much self-sufficient.

Authorities now expect the 2021-22 harvest to come in at around 107 million tons, down from a February estimate of 111 million. That may still be too optimistic as traders and flour millers forecast 98 million to 102 million tons.

Government purchases of wheat for the country’s food aid program, the world’s largest, are expected to be less than half of levels last year, according to the food ministry. That prompted authorities to distribute more rice in some states, and also to restrict exports of wheat flour and other products.

Consumer wheat inflation has held above 9% year-on-year since April and surged to 11.7% in July. Wholesale prices were up even more, by 13.6% in July, official data show. That’s creating a headache for the central bank, which is trying to bring overall inflation, currently near 7%, back under its 6% target.

Wheat is India’s biggest winter crop, with planting happening in October and November and harvesting in March and April. There are also concerns about its rice production, which could be the next challenge for global food supply.

“Cereal inflation is a concern on the back of lower paddy sowing,” said Sameer Narang, an economist at ICICI Bank in Mumbai. The rising cereal prices are likely to continue for a while, he said.

Aug 21, 2022

Riaz Haq

In the 2022 Global Hunger Index, Pakistan ranks 99th out of the 121 countries with sufficient data to calculate 2022 GHI scores. With a score of 26.1, Pakistan has a level of hunger that is serious.

https://www.globalhungerindex.org/pakistan.html

In the 2022 Global Hunger Index, India ranks 107th out of the 121 countries with sufficient data to calculate 2022 GHI scores. With a score of 29.1, India has a level of hunger that is serious.

https://www.globalhungerindex.org/india.html

-------------------

India also ranks below Sri Lanka (64), Nepal (81), Bangladesh (84), and Pakistan (99). Afghanistan (109) is the only country in South Asia that performs worse than India on the index.

https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/india-ranks-107-out-of-121-c...

India ranks 107th among 121 countries on the Global Hunger Index, in which it fares worse than all countries in South Asia barring war-torn Afghanistan.

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is a tool for comprehensively measuring and tracking hunger at global, regional, and national levels. GHI scores are based on the values of four component indicators — undernourishment, child stunting, child wasting and child mortality. Countries are divided into five categories of hunger on the basis of their score, which are ‘low’, ‘moderate’, ‘serious’, ‘alarming’ and ‘extremely alarming’.

Based on the values of the four indicators, a GHI score is calculated on a 100-point scale reflecting the severity of hunger, where zero is the best score (no hunger) and 100 is the worst.

India’s score of 29.1 places it in the ‘serious’ category. India also ranks below Sri Lanka (64), Nepal (81), Bangladesh (84), and Pakistan (99). Afghanistan (109) is the only country in South Asia that performs worse than India on the index.

Seventeen countries, including China, are collectively ranked between 1 and 17 for having a score of less than five.

India’s child wasting rate (low weight for height), at 19.3%, is worse than the levels recorded in 2014 (15.1%) and even 2000 (17.15), and is the highest for any country in the world and drives up the region’s average owing to India’s large population.

Prevalence of undernourishment, which is a measure of the proportion of the population facing chronic deficiency of dietary energy intake, has also risen in the country from 14.6% in 2018-2020 to 16.3% in 2019-2021. This translates into 224.3 million people in India considered undernourished.

But India has shown improvement in child stunting, which has declined from 38.7% to 35.5% between 2014 and 2022, as well as child mortality which has also dropped from 4.6% to 3.3% in the same comparative period. On the whole, India has shown a slight worsening with its GHI score increasing from 28.2 in 2014 to 29.1 in 2022. Though the GHI is an annual report, the rankings are not comparable across different years. The GHI score for 2022 can only be compared with scores for 2000, 2007 and 2014..

Globally, progress against hunger has largely stagnated in recent years. The 2022 GHI score for the world is considered “moderate”, but at 18.2 in 2022 is only a slight improvement from 19.1 in 2014. This is due to overlapping crises such as conflict, climate change, the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the Ukraine war, which has increased global food, fuel and fertiliser prices and is expected to "worsen hunger in 2023 and beyond."

The prevalence of undernourishment, one of the four indicators, shows that the share of people who lack regular access to sufficient calories is increasing and that 828 million people were undernourished globally in 2021.

There are 44 countries that currently have “serious” or “alarming” hunger levels and “without a major shift, neither the world as a whole nor approximately 46 countries are projected to achieve even low hunger as measured by the GHI by 2030,” notes the report.

Oct 14, 2022

Riaz Haq

From Times of India:

The decline in India’s rankings on a number of global opinion-based indices are due to "cherry-picking of certain media reports" and are primarily based on the opinions of a group of unknown “experts”, a recent study has concluded.

A new working paper titled "Why India does poorly on global perception indices" found that while such indices cannot be ignored as "mere opinions" since they feed into World Bank’s World Governance Indicators (WGI), there needs to be a closer inspection on the methodology used to arrive at the data.

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/indias-declining-rank-in-...

The findings were published by Sanjeev Sanyal, member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister and Aakanksha Arora, deputy director of (EAC to PM).

In the report, the authors conducted a case study of three o ..

In the report, the authors conducted a case study of three

opinion-based indices: Freedom in the World index, EIU

Democracy index and Variety of Democracy.

They drew four broad conclusions from the study:

1) Lack of transparency: The indices were primarily based on

the opinions of a tiny group of unknown “experts”.

2) Subjectivity: The questions used were subjective and

worded in a way that is impossible to answer objectively

even for a country.

3) Omission of important questions: Key questions which

are pertinent to a measure of democracy, like “Is the head of

state democratically elected?”, were not asked.

4) Ambiguous questions: Certain questions used by these

indices were not an appropriate measure of democracy

across all countries.

Here's a look at the three indices examined by the study:

Freedom in the World Index

India’s score on the US-based Freedom in the World Index —

an annual global report on political rights and civil liberties

— has consistently declined post 2018.

It's score on civil liberties was flat at 42 till 2018 but dropped

sharply to 33 by 2022. It's political rights score dropped from

35 to 33. Thus, India’s total score dropped to 66 which places

India in the “partially free” category – the same status it had

during the Emergency.

The study found that only two previous instances where

India was considered as Partially Free was during the time of

Emergency and then during 1991-96 which were years of

economic liberalisation.

"Clearly this is arbitrary. What did the years of Emergency,

which was a period of obvious political repression,

suspended elections, official censoring of the press, jailing of

opponents without charge, banned labour strikes etc, have

in common with period of economic liberalisation and of

today," the study asked.

It concluded that the index "cherry-picked" some media

reports and issues to make the judgement.

The authors further found that in Freedom House's latest

report of 2022, India’s score of the Freedom in the World

Index is 66 and it is in category "Partially Free".

"Cross country comparisons point towards the arbitrariness

in the way scoring is done. There are some examples of

countries which have scores higher than India which seem

clearly unusual. Northern Cyprus is considered as a free

territory with a score of 77 (in 2022 report). It is ironical as

North Cyprus is not even recognised by United Nations as a

country. It is recognised only by Turkey," the authors noted.

Economist Intelligence Unit

In the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) Democracy Index,

published the research and consulting arm of the firm that

publishes the Economist magazine, India is placed in the

category of “Flawed Democracy”.

Its rank deteriorated sharply from 27 in 2014 to 53 in 2020

and then improved a bit to 46 in 2021. The decline in rank

has been on account of decline in scores primarily in the

categories of civil liberties and political culture.

The authors found that list of questions used to determine

the outcome was "quite subjective", making objective

Nov 22, 2022

Riaz Haq

The Sardar family was eligible for 35 kilos of rice and grain monthly from a government-run aid programme but had been approved for just two kilos because they lacked the right ID documents, according to Paul. “They had been without even these minimal benefits for six months,” she told The New Humanitarian.

Sunil Agarwala, the district magistrate of Jhargram, refuted the allegations, telling The Hindu newspaper they were "baseless", while insisting that Sardar’s death “was due to illness, TB, and other reasons”.

According to the World Health Organization, undernutrition is a key driver of TB, while malnutrition also makes TB therapy less effective and raises the risk of TB-related death.

The recently published Medical Certification Cause of Death (MCCD), 2020 report found that fewer than a quarter of the 81,15,882 registered deaths in India that year had known causes. Hunger activists are alarmed that a country with 1.4 billion people can only verify the causes of 22.5% of its documented fatalities.

Swati Narayan, assistant professor at the School for Public Health and Human Development at O.P. Jindal Global University, told The New Humanitarian that medical workers are unlikely to catch if the cause of death is starvation given how post-mortems are typically carried out.

She said it was crucial to also consider the person's socioeconomic position and the condition of their body, including the weight of their organs, visceral fat, and diseases brought on by a weaker immune system and malnutrition.

“The post-mortem reports are not an accurate reflection of hunger or starvation deaths in the country,” Narayan said. “Oral autopsies are much better at determining if the cause of death was hunger.”

Worsening hunger and the fight for a stronger safety net

Question marks around Sardar’s death and others like it – a similar case involving three “hunger deaths” in the same family went before the high court last month in Jharkhand, which borders West Bengal to the east – come amid signs of growing food insecurity in India.

The 2022 Global Hunger Index ranks India at 107 out of 121 nations, six places lower than its previous ranking, and below the likes of Ethiopia, Bangladesh, and Pakistan.

While India remains in the “serious” category rather than “alarming” or “very alarming”, it recorded the highest percentage (19.3%) of any country of children under five who are “wasting”, meaning they’re below average weight for their height.

The pandemic made hunger worse, but income losses and rising debt continued to drive it up long after the worst of the health crisis had passed. A survey by the Right to Food Campaign in late 2021/early 2022 found that nearly 80% of respondents faced food insecurity, and almost half had run out of food the previous month.

However, the hunger problems also pre-date COVID. India’s last National Family Health Survey, which used data from 2019, found that stunting – a sign of chronic malnutrition – had risen in 11 out of the 17 states. In 13 states, wasting had also increased.

Jan 3, 2023