PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

National Geographic's Paul Salopek recently came upon a site in Pakistan's Salt Range where Muslim scientist Abu-Raihan Al-Biruni accurately measured the size of the earth in the 11th century. In it, Salopek sees the revival of the Islamic Golden Age. He characterizes the ancient Silk Road of as "dynamic but collapsed experiment in multilateralism". He thinks the revival of the Islamic Golden Age is linked to "China's 21st century version of the Silk Road". Salopek believes that President Donald Trump's four years in the White House and the COVID19 pandemic have accelerated America's decline and China's rise. Here's how he describes it in a recent opinion piece in the New York Times entitled "Shadows on the Silk Road: Finding omens of American decline on a long walk across Asia":

"The most memorable archaeological ruins from the Silk Road’s glory years rot atop a hill about 60 miles southeast of Islamabad (the Capital of Pakistan). No monuments or signs mark the Nandana Fort. Few people go there. But it was where, in the early 11th century, the Central Asian scholar al-Biruni became the first person to measure, with astonishing precision, the size of Earth. His calculations, based on brilliant trigonometry, landed within 200 miles of the 24,902-mile circumference of our shared planet".

|

| Pakistan Postage Stamp Honoring Al-Biruni. Nandana Fort in Background |

It was Sultan Mahmood Ghaznavi who took Al-Biruni along with him after his conquest of India. Al-Biruni traveled all over India for 20 years, and studied Indian philosophy, Mathematics and Geography. Pakistan issued a postage stamp honoring Al-Biruni in 1973. The stamp has a picture of Al-Biruni with the ruins of Nandana Fort in the background.

|

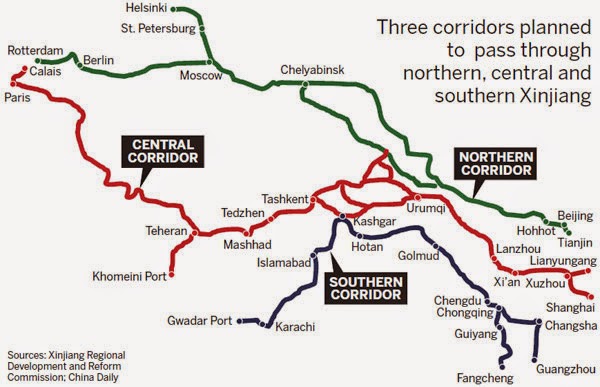

| China's New Silk Road. Source: China Daily |

Salopek found a lot of history of the Islamic Golden Age as he traveled along the Silk Road. Here's a brief excerpt of his Op Ed in the New York Times:

"The Islamic Golden Age of science and art that predated the Italian Renaissance by 400 years was illuminated by Turkic and Persian thinkers from the eastern rim of the Abbasid Caliphate, in what is today Central Asia, western China and parts of Iran. ..... Muhammad al-Khwarizmi, a ninth-century genius who helped formulate the precepts of algebra, has lent his name to the word “algorithm.” A century later, the brilliant polymathic Abu Rayhan Muhammad al-Biruni wrote more than 140 manuscripts on everything from pharmaceuticals to the anthropology of India. (A typical al-Biruni title: “The Exhaustive Treatise on Shadows.”) Probably the most celebrated Silk Road sage of all was Abu Ali al-Hussein ibn Sina, revered in the West as Avicenna, who in the 11th century compiled an encyclopedia of healing that was still in use by European doctors as late as the 18th century. Avicenna’s “Canon of Medicine” accurately diagnosed diabetes by tasting sweetness in urine. Its pharmacopoeia cataloged more than 800 remedies. A millennium ago, Avicenna advocated quarantines to control epidemics. What would he make, I wondered, of the willed ignorance of today’s anti-maskers in the United States?"

Salopek sees parallels between America's Trumpism and India's Hindu Nationalism. He is just as pessimistic about India as he is about his home country of the United States. Here's what he sees from the top of Nanada Fort ruins:

"I climbed a broken fort wall and peered east. Ahead unspooled 17 months of hiking across India, yet another democracy cartwheeling into an abyss of right-wing populism. Riding a wave of Hindu nationalism, one Indian state all but criminalized marriages between Hindu and Muslim citizens".

From the top of Nandana Fort, Salopek also sees China which he describes in the following words:

"In the blue distance beyond sprawled China. Its economic output in 2019, according to one report, hit 67 percent of the United States’ gross domestic product. The gap between China and the United States is shrinking as China is the only major economy expected to report economic growth for 2020 despite the pandemic. And brawling with itself at some crossroad truck stop far over the horizon lay my lost homeland".

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Is Fareed Zakaria Souring on India?

US Needs to Promote Democracy at Home

Rise and Fall of the Islamic Civilization

Al-Khwarizmi: Origins of Artificial Intelligence in Islamic Golden Age

Pakistani Woman Leads Global Gender Parity Campaign

Muslims Have Few Nobel Prizes

Ibn Khaldun: The Father of Modern Social Sciences

Obama Speaks to the Muslim World

Lost Discoveries by Dick Teresi

Physics of Christianity by Frank Tipler

What is Not Taught in School

How Islamic Inventors Changed the World

Jinnah's Pakistan Booms Amidst Doom and Gloom

Riaz Haq

“For centuries before the early modern era, the intellectual centers of excellence of the world, the Oxfords and Cambridges, the Harvards and Yales, were not located in Europe or the west, but in Baghdad and Balkh, Bukhara and Samarkand,” the British historian Peter Frankopan wrote in “The Silk Roads: A New History of the World.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/16/opinion/walk-across-world-americ...

Jan 19, 2021

Riaz Haq

China’s Ascent

The rise of China will have far-reaching consequences—the world should get ready

By Keyu Jin

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2019/06/rise-of-china-ji...

China in 2040 will look on the face of things to be a mighty economic power. Under plausible projections, it will have firmly established itself as the largest economy in the world, with 60 to 70 percent of the US income level. But in 20 years, China will still be a developing economy by many measures—its financial development will lag its economic development, and many economic and policy distortions may still persist.

In that scenario, the world must be prepared for China to be its first systemic emerging market economy. It should brace for greater volatility and uncertainty as China becomes more intermeshed with global financial markets. It should prepare for a China that emits shocks distinctive to developing economies—but on a much larger scale and with greater thrust and impetus.

Every significant policy move, stock market panic, and cyclical upswing or downswing in China can plausibly diffuse and propagate through the web of financial networks that links nations. In China today, 70 percent of investors in capital markets are retail investors, quick to react to noise and changes in sentiment. Mercurial stock markets and volatile exchange rates may become the rule, not the exception.

Currently, China is already inadvertently sending shocks to the rest of the world, despite its small international financial exposure. My own research with Yi Huang shows that it is not only policy shocks (monetary and fiscal) that spill over to the rest of the world but also the shocks of policy uncertainty.

In a country where reforms big and small happen on a regular basis, where policy moves often instigate cyclical fluctuations rather than subdue them, where policy direction and strategy are based on experimentation rather than experience, uncertainty can be a first-order menace to overly sensitized financial markets.

Our research shows that during 2000–18, Chinese policy uncertainty shocks significantly affected not only economic variables, such as world industrial production and commodity prices, but also key financial variables, including global stock prices and bond yields, the MSCI World Index, and financial volatility.

Now imagine China in 2040, more consequential and with a greater number of channels open to the rest of the world—whether cross-border bank lending, portfolio holdings, capital flows, or a more dominant renminbi. In that scenario, shocks emanating from China would not only propagate more swiftly and potently, they would also be amplified and expanded through its increasing and diverse financial channels.

The rise of China today bears much similarity to the ascent of the United States in the late 19th century. Although it was growing rapidly and catching up with European countries, it had the developing economy malaise of unsophisticated capital markets. Corporate governance was riddled with problems and banking crises occurred regularly; weak financial intermediaries and a shortage of financial assets, along with the absence of a lender of last resort, prevented the efficient mobilization of capital. The vagaries of the US economy and the financial panic in 1873 were fully transmitted to Europe and Great Britain, which had significant exposure to the US economy.

Jan 24, 2021

Riaz Haq

South-East Asian countries are trapped between two superpowers

Balancing China and America will be tough

https://www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2020/11/17/south-east-asi...

NO PART OF the world risks suffering more from the economic, strategic and military rivalry now playing out between the United States and China than the 11 nations of South-East Asia. And that rivalry will intensify in 2021.

On the one hand, many in the region are wary of President Xi Jinping’s mission to reclaim for China the centrality it enjoyed in East Asia before the imperial depredations by the West and Japan in the 19th and 20th centuries. It is not just that China is aggressively challenging the maritime and territorial claims of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam in the South China Sea, through which the majority of China’s seaborne trade passes. It is also that Mr Xi’s call for “Asian people to run the affairs of Asia” sounds like code for China running Asia. As a Chinese foreign minister once told a gathering of the ten-country Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN): “China is a big country and [you] are small countries, and that is just a fact.”

On the other hand, while ASEAN members welcome America as the dominant military power in the region to counter China’s growing heft, they know that conflict would be disastrous for them. South-East Asian diplomats did not loudly cheer the anti-China rhetoric of President Donald Trump’s administration, which is unlikely to soften much under Joe Biden. And no wonder. Many of the region’s governments are hostile to democracy, and few see America’s political model as one to emulate.

Above all, China is too close and already too mighty to turn against. It is by far South-East Asia’s biggest trading partner and its second-biggest investor, behind Japan. ASEAN’s prosperity is as bound to China as its supply chains are. And as Sebastian Strangio, a perceptive observer of the region, points out in a new book, “In the Dragon’s Shadow”, South-East Asia has a powerful stake in China’s growth and stability: historically, turmoil in China has spread instability southward.

So, how not to get caught between the two giants? The region’s strategists remind themselves that, when it comes to great-power rivalry, things have been worse. At the height of the cold war, bloody conflict in Indo-China, along with communist insurgencies elsewhere, threatened to reduce South-East Asian autonomy to zero. Those concerns, and the need for a mechanism to manage their mutual mistrust, were catalysts for Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Singapore to form ASEAN more than 50 years ago. And today? At least, the strategists say, with black humour, China and the United States have not carved up the region between them.

As for 2021, the region’s experience in managing great-power rivalry will come to the fore. South-East Asia has lived under China’s armpit for millennia, and ASEAN’s member countries have dealt with the American presence since the second world war. The approach will be to “hedge, balance and bandwagon” between the two, says Bilahari Kausikan, formerly Singapore’s top diplomat. Students of international relations are usually taught that only one of these three approaches is possible at any time. Yet pragmatic South-East Asians, Mr Kausikan argues, have a knack for doing all three. One example in 2021: just as the Philippines under President Rodrigo Duterte will keep wooing Mr Xi over Chinese investment, expect a rapid improvement in once-strained military ties with America. South-East Asia in 2021 will also do more to invite other powers, notably Japan, South Korea, Australia and India, to share in both regional prosperity and security.

Jan 29, 2021

Riaz Haq

South-East Asian countries are trapped between two superpowers

Balancing China and America will be tough

https://www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2020/11/17/south-east-asi...

So, how not to get caught between the two giants? The region’s strategists remind themselves that, when it comes to great-power rivalry, things have been worse. At the height of the cold war, bloody conflict in Indo-China, along with communist insurgencies elsewhere, threatened to reduce South-East Asian autonomy to zero. Those concerns, and the need for a mechanism to manage their mutual mistrust, were catalysts for Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Singapore to form ASEAN more than 50 years ago. And today? At least, the strategists say, with black humour, China and the United States have not carved up the region between them.

As for 2021, the region’s experience in managing great-power rivalry will come to the fore. South-East Asia has lived under China’s armpit for millennia, and ASEAN’s member countries have dealt with the American presence since the second world war. The approach will be to “hedge, balance and bandwagon” between the two, says Bilahari Kausikan, formerly Singapore’s top diplomat. Students of international relations are usually taught that only one of these three approaches is possible at any time. Yet pragmatic South-East Asians, Mr Kausikan argues, have a knack for doing all three. One example in 2021: just as the Philippines under President Rodrigo Duterte will keep wooing Mr Xi over Chinese investment, expect a rapid improvement in once-strained military ties with America. South-East Asia in 2021 will also do more to invite other powers, notably Japan, South Korea, Australia and India, to share in both regional prosperity and security.

Hedging, balancing and bandwagoning rests, admittedly, on one big assumption: that neither America nor China really intends to decouple their two economies entirely. That calculation is probably right, and even if hard-nosed competition and negotiation between the two powers reconfigures global supply chains, South-East Asians still intend to profit from that.

Even so, it is a gamble, and other risks loom. Not the least of them is maintaining ASEAN solidarity—China has already tried to drive a wedge into the organisation by turning Cambodia and Laos, for now, into client states. Mr Xi’s increasing claims to speak for all ethnic Chinese overseas, including 30m South-East Asians of Chinese ancestry, raise the risk of nativist demagogues using anti-China feelings to whip up ethnic hatred.

Perhaps the most nail-biting risk of all is of some unintended clash between China and America over the South China Sea. In the event of military conflict, the hedge, the balance and the bandwagon will not get anyone very far at all.

Jan 29, 2021

Riaz Haq

Focus on Pakistan Navy by Ejaz Haider

https://www.thefridaytimes.com/focus-on-pakistan-navy/

Ahmed Ibn-e Majid was an Arab navigator and cartographer whose book, “The Book of the Benefits of the Principles and Foundations of Seamanship,” was used by navigators right up to the 18th Century. The book discussed the difference between coastal and open-sea sailing, the locations of ports from East Africa to Indonesia, accounts of the monsoon and other seasonal winds, typhoons and other topics for professional navigators.

--------

Pakistan Navy is demonstrably the most neglected service. There are reasons for this state of affairs, all of them bad.

One, as the largest and senior-most service, the Pakistan Army has traditionally dominated military-operational thinking and plans.

Two, the Army’s politico-praetorian streak has added another dimension to its heft and further ensured it gets the lion’s share of defence allocations.

Three, air and naval platforms are almost always big ticket items and require monies that are difficult to find in a poor country like Pakistan.

Four, historically, even when Muslim empires dominated large parts of the world, the ruling dynasts — barring some attempts by the Ottomans — neglected naval power. To stress the salience of this point, one only need contrast the naval exploits of Italian city-states, the Portuguese, the Dutch and the English with, for instance, the Muslim rulers of India.

What makes this Muslim reticence even more surprising is the fact that Arabs were great seafarers and navigators and traded with the littoral states of the Indian Ocean. For example, Ahmed Ibn-e Majid was an Arab navigator and cartographer whose book, “The Book of the Benefits of the Principles and Foundations of Seamanship,” was used by navigators right up to the 18th Century. The book discussed the difference between coastal and open-sea sailing, the locations of ports from East Africa to Indonesia, accounts of the monsoon and other seasonal winds, typhoons and other topics for professional navigators. [NB: for a detailed account of how difficult seafaring was and the five different seafaring traditions in the ancient world, the first chapter of Daniel Headrick’s Power Over Peoples… is a great primer. I am thankful to Dr Ilhan Niaz for pointing it to me.]

Five, this land-focused approach to warfare has continued in Pakistan. As mentioned above, this is due to the power of the army which (a) remains bound by traditional thinking and (b) has stymied any fresh thinking about war itself, including maritime security and the importance of naval power to a state’s offensive and defensive capabilities.

As I said earlier, these are all bad reasons.

Yet, despite these handicaps, the PN has acted professionally and remains prepared for the defence of territorial waters. To expect any more from it would be like expecting a sedan to win a Formula 1 race. Accordingly, the Pakistan Navy’s performance has to be evaluated within the functions and framework of a brown-, or at most green-water navy.

The PN is holding its 7th AMAN (Peace) exercise off the coast of Karachi in February. AMAN exercises began in March 2007. The exercise, which has harbour and sea phases, has drawn naval contingents from around the world. This year’s new entrant is a Russian naval contingent from its Baltic Fleet.

According to the Russian Navy’s website, Russia plans to send a frigate, a patrol ship, a tugboat, a sea-based helicopter and some other units. This is also the first time since 2011 that Russia will take part in a naval exercise with naval contingents from NATO countries. The last time Russian naval continent participated in naval drills with NATO vessels was in 2011 in a NATO-led exercise codenamed Bold Monarch held off the coast of Spain.

Exercise AMAN focuses on interoperability with other navies in anti-Piracy and counterterrorism operations. The drill allows navies to discuss best practices and establish operational relationships towards the common goal of maritime security.

Jan 30, 2021

Riaz Haq

8 facts about Omar Khayyam, the man who gave base to Gregorian calendar

He was a famous astronomer and invented Jalali Calendar became the base of other calendars and is also known to be more accurate than the Gregorian calendar.

https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/gk-current-affairs/story/...

Jan 30, 2021

Riaz Haq

Genome of nearly 5000-year-old woman links modern Indians to ancient civilization | Science

https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/09/genome-nearly-5000-year-old...

The Science paper, also led by Reich, notes that modern people from North India also bear the genetic marks of ancient interbreeding with herders from the Eurasian steppe, a vast grassland that stretches across northern Asia, moving southward around 2000 B.C.E. Those steppe herders carried European DNA from previous interbreeding events, the authors note, explaining the once-perplexing genetic link between Europeans and South Asians. Over the next few thousand years, the groups in north and south India intermixed, leading to the modern population’s complex ancestral mix.

One surprise concerns DNA related to ancient Iranians, which was previously found to be prevalent in modern South Asians. The finding seemed to back a popular belief among anthropologists that migrants from the Fertile Crescent—which comprises modern-day Iran and gave rise to the world’s first farmers who began to rove about 10,000 years ago—moved east at some point and mixed with South Asian hunter-gatherers, introducing agriculture to the Indian subcontinent. Yet the new study suggests the Iranian-related DNA in both the Indus individuals and modern Indians actually predates the rise of agriculture in Iran by some 2000 years. In other words, that Iranian-related DNA came from interbreeding with 12,000-year-old hunter-gatherers, not more recent farmers, Reich explains.

Jan 30, 2021

Riaz Haq

The great Himalayas were formed around ten million years ago by the collision of the Indian continental plate, moving northward through the Indian Ocean, with Eurasia. India today is also the product of collisions of cultures and people. Consider farming. The Indian subcontinent is one of the breadbaskets of the world—today it feeds a quarter of the world’s population—and it has been one of the great population centers ever since modern humans expanded across Eurasia after fifty thousand years ago. Yet farming was not invented in India. Indian farming today is born of the collision of the two great agricultural systems of Eurasia. The Near Eastern winter rainfall crops, wheat and barley, reached the Indus Valley Valley sometime after nine thousand years ago according to archaeological evidence—as attested, for example, in ancient Mehrgarh on the western edge of the Indus Valley in present-day Pakistan.13 Around five thousand years ago, local farmers succeeded in breeding these crops to adapt to monsoon summer rainfall patterns, and the crops spread into peninsular India.14 The Chinese monsoon summer rainfall crops of rice and millet also reached peninsular India around five thousand years ago. India may have been the first place where the Near Eastern and the Chinese crop systems collided. Language is another blend. The Indo-European languages of the north of India are related to the languages of Iran and Europe. The Dravidian languages, spoken mostly by southern Indians, are not closely related to languages outside South Asia. There are also Sino-Tibetan languages spoken by groups living in the mountains fringing the north of India, and small

Reich, David. Who We Are and How We Got Here (pp. 151-152). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Jan 30, 2021

Riaz Haq

The great Himalayas were formed around ten million years ago by the collision of the Indian continental plate, moving northward through the Indian Ocean, with Eurasia. India today is also the product of collisions of cultures and people. Consider farming. The Indian subcontinent is one of the breadbaskets of the world—today it feeds a quarter of the world’s population—and it has been one of the great population centers ever since modern humans expanded across Eurasia after fifty thousand years ago. Yet farming was not invented in India. Indian farming today is born of the collision of the two great agricultural systems of Eurasia. The Near Eastern winter rainfall crops, wheat and barley, reached the Indus Valley Valley sometime after nine thousand years ago according to archaeological evidence—as attested, for example, in ancient Mehrgarh on the western edge of the Indus Valley in present-day Pakistan.13 Around five thousand years ago, local farmers succeeded in breeding these crops to adapt to monsoon summer rainfall patterns, and the crops spread into peninsular India.14 The Chinese monsoon summer rainfall crops of rice and millet also reached peninsular India around five thousand years ago. India may have been the first place where the Near Eastern and the Chinese crop systems collided. Language is another blend. The Indo-European languages of the north of India are related to the languages of Iran and Europe. The Dravidian languages, spoken mostly by southern Indians, are not closely related to languages outside South Asia. There are also Sino-Tibetan languages spoken by groups living in the mountains fringing the north of India, and small

pockets of tribal groups in the east and center that speak Austroasiatic languages related to Cambodian and Vietnamese, and that are thought to descend from the languages spoken by the peoples who first brought rice farming to South Asia and parts of Southeast Asia. Words borrowed from ancient Dravidian and Austroasiatic languages, which linguists can detect as they are not typical of Indo-European languages, are present in the Rig Veda, implying that these languages have been in contact in India for at least three or four thousand years.15

Reich, David. Who We Are and How We Got Here (pp. 151-152). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Jan 30, 2021

Riaz Haq

#Pakistan's #GilgitBaltistan regional govt has proposed a new transit and trade route linking #Xinjiang to #Kashmir and extending to #Afghanistan. Will it increase #China-Pak #military interoperability against #Indian forces in the region? #Ladakh #CPEC https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/economics/article/3119850/will-new-r...

In a video posted on social media platforms this month, GB chief minister Khalid Khurshid announced plans to drill a road tunnel through the mountains to connect Astore to the Neelum Valley in the Azad Kashmir region, where much of the LOC is thinly demarcated by the Neelum and Jhelum rivers.

----------

Proposals floated this month by the government of the Pakistan-administered Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) region primarily aim to pave the way for a new transit and trade route between China and Pakistan’s neighbours Afghanistan and Iran.

Currently, China and Pakistan are connected only by the Karakoram Highway, completed in 1978, via a single crossing in the Khunjerab Pass.

However, the route of a proposed new border road from Yarkand – on GB’s border with the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region – also suggests strong strategic motivations because it would open a new supply line from China to Pakistani forces deployed along the Line of Control (LOC).

As Pakistan, Bangladesh ties thaw, India keeps close watch on them – and China

14 Jan 2021

The 740km LOC divides Kashmir roughly into two halves governed by India and Pakistan. Its northernmost point, the India-held Siachen Glacier, is located next to the western extreme of the disputed 3,488km China-India border known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

The GB government’s public works department was instructed on January 15 to prepare a “project concept clearance proposal” for a 10-metre-wide road capable of being used by trucks, from the Mustagh Pass on the border with the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region via the eastern GB region of Skardu, where the Siachen Glacier is located.

The proposed new road would be linked to Yarkand in Xinjiang, and enter GB 126km west of Ladakh, crossing the major supply artery from the Karakoram Highway near Skardu city. From there, it would run south through the high-altitude Deosai Plateau to the Astore Valley, where the southern flank of GB meets the LOC amid the Himalayas.

Washington-based analyst Sameer Lalwani told This Week In Asia there were potentially three logistics and strategic effects of enhanced China-Pakistan connectivity.

“It could deepen trade links by enhancing transport capacity; enable great Pakistan military mobility in any contingency, threatening India’s hold over the Siachen Glacier; and it can even facilitate greater China-Pakistan military coordination that generates peacetime dilemmas and wartime complications for India,” he said.

The proposed Xinjiang-GB-Kashmir road would “certainly ring alarm bells in New Delhi, which has been acutely sensitive to deepening China-Pakistan strategic and military ties over the past decade”, said Lalwani, who is director of the South Asia programme at the Stimson Center, a Washington-based think tank.

“It may also result in the Indian military – which has already sunk considerable resources to retain control of Siachen – concentrating an even greater proportion of money, manpower, and materiel to its continental defences at the expense of maritime power projection,” he said.

Jan 31, 2021

Riaz Haq

The spatial competition between containerised rail and sea transport in Eurasia

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-019-0334-6

The competition in space between rail and sea transport is of great significance to the integration of Eurasia. This paper proposes a land and sea transport spatial balance model for container transport, which can extract a partition line on which transport costs by rail and sea are equal given a destination. Four scenarios are discussed to analyse the effects of different factors on the model. Then the model is empirically tested on current rail and sea transport networks to identify the transport competition pattern in Eurasia. The location of destinations, the freight costs, and time costs are the three main factors affecting the model. Among them, time costs are determined by the value of a container and its contents, the interest rate, and by time differences between land and sea transport. The case study shows that Eurasia forms a transport competition pattern with a land area to sea area ratio of about 1:2; this ratio, however, changes to 1:1 when time costs are considered. Further, the land and sea transport balance lines are consistent with the theories of geopolitics, which indicate that the same processes may exist in the spatial pattern of geo-economics and geopolitics in Eurasia. According to the balance lines, we get a spatial partition, dividing Eurasia into the land transport preferred area, the land–sea transport indifference area, and the sea transport preferred area. The paper brings a new perspective to the exploration of geopolitical economic spatial patterns of Eurasia and provides a practical geographic theory as an analytic basis for the implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative.

-----------

There are some limitations in the case study too. First, it is based on the precondition of using Beijing and Berlin as the destinations, and the current fluctuated values of speeds, goods and freight rates are all set unique. According to the simulation under different scenarios, preferential policies for transportation could be carried out by governments or transport companies in different places, which could further strengthen the practicality of our model. Specifically, some countries (such as India) oppose China’s BRI (Blah, 2018; Pattanaik, 2018). Therefore, we could add evaluations of the strategies for infrastructure construction, of such countries, in the future. Second, container transportation is a complex process. The extent to which the cross-border transportation between countries is frictionless will affect the land transport pattern. Moreover, these factors are difficult to quantify and have not been considered in this paper, such as unequal freight cost rates in different countries, different capabilities and widths of rails, time spent at ports, tariffs, insurance costs and so on, which may also influence actual costs. Third, in not considering the road network, this paper presents a basic possible pattern of land and sea transport balance based on the current railway and maritime networks, which may bias our results. At a strategic level, the results can offer positive suggestions to influence a better approach for transportation. It will, however, be necessary for individual decision-makers to make accurate calculations of the costs of different routes at a micro-level. Additionally, container shipping on the northern sea route is a potential transport corridor (Verny and Grigentin, 2009), it could be included in the future study. Moreover, because of the organisational system and mature development of transport companies, the related data of container transport are easy to obtain, which helps determining the costs and speeds more easily. In contrast, it is hardly to collect datasets of bulk transport. However, the effect of bulk transport may be significant because it is likely to form a large proportion of global maritime trade (J.P.Morgan Asset Management, 2019). This may render some ports more economically viable.

May 9, 2021

Riaz Haq

The spatial competition between containerised rail and sea transport in Eurasia

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-019-0334-6

In the future, the BRI will be significant to the integration of economic trade in Eurasia, following the premise that land and sea transport should find a spatial balance. In fact, analysis of the competition and cooperation between land and sea transport can also be of theoretical significance for transport geography. This paper presents a LSTSB model based on the conceptualised Eurasia and simulates different land–sea transport scenarios. We then identify the transport balance lines by applying the model to Eurasia and present the partition of land and sea transport dominated areas in line with the theories of geopolitics.

The main insights are as follows:

Four scenarios based on different locations of destination, different freight costs, different values of a container’s goods and different speeds of transport are simulated using the theoretical model. They show that these basic factors influence the spatial balance lines of transportation. The results indicate that land transport is relatively competitive with sea transport but that this depends on different factors. Land transport may be undervalued at present due to long-term cooperation behaviour between governments or enterprises with maritime companies.

The case study shows that in terms of freight costs, maritime transport has an obvious advantage in Eurasia. The transport spatial balance line divides the Eurasian continent into a land and sea transport competitive pattern with an area ratio of 1:2. However, this ratio changes to 1:1 when we take time costs into consideration. Results show that the Economic Belt on road has economic feasibility and rationality.

Furthermore, the spatially competitive pattern of land–sea transport in Eurasia is highly consistent with geopolitical theories. This paper presents a partition of transport areas based on the calculation of balance lines, showing the land transport preferred area, the sea transport preferred area and the land–sea transport indifference area. The partition shows that the China–Russia–EU region, located in the land transport preferred area and the land–sea transport indifference area, is the key pivot area of integration influencing the current economic geographic imbalance in Eurasia. Further, it can serve as the analytic basis underpinning the necessity of increasing cooperation between China and the EU under the BRI, which is in the land–sea indifference area. Thus, the LSTSB model can bring a new perspective to the discussion of the spatial pattern of geopolitics and geo-economics in Eurasia.

May 9, 2021

Riaz Haq

Impact of Transport Cost and Travel Time on Trade under China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)

Khalid Mehmood Alam

https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jat/2019/7178507/

China is the second biggest economy in the world and almost 40% of its trade in 2016 is transported through the South China Sea. China needs a small, secure, and low-cost path to trade with Europe and the Middle East and China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is a feasible solution to this requirement. This research analyzes the effect of CPEC on trade in terms of transport cost and travel time. In addition, the study compares the existing routes and the new CPEC route. The research methodology consists of qualitative and descriptive statistical methods. The variables (transport cost and travel time) are calculated and compared for both the existing route and new CPEC route. The results show that transport cost for 40-foot container between Kashgar and destination ports in the Middle East is decreased by about $1450 dollars and for destination ports in Europe is decreased by $1350 dollars. Additionally, travel time is decreased by 21 to 24 days for destination ports in the Middle East and 21 days for destination ports in Europe. The distance from Kashgar to destination ports in the Middle East and Europe is decreased by 11,000 to 13,000 km.

Transportation is the shifting of goods by truck, rail, road, and sea and is reasoned as an important indicator for economic development [1]. Transport has two main parts. The first part represents vehicles that are either van, truck, rails, airplanes, or ships and second part represents the transport infrastructure such as roads, highways, seaways, airways, and railway tracks on which transport runs smoothly. In the recent days, both parts of transportation are considered as an important factor of trade and help in reducing transportation cost and travel time. The selection of transport mode for delivery of goods within less time and minimum cost is important to maximize the profit. Every state tries its best to discover short trade routes that can reduce trade cost and transfer time. To enhance their trade, countries invest in transport infrastructures like roads and rails and adequate transport infrastructure can potentially reduce transport cost and travel time. Transport cost and travel time are considered as the most important among all factors [2].

Shipping industry plays an significant part in the development of trade and about 80% of world trade is transported by the international shipping industry [3, 4]. The import and export of goods on large scale are not possible without shipping [5]. China is the second biggest economy and energy user in the world and safety of the oil supply chain stay the essential idea of China’s strategies [6]. China is importing about 83% of oil supplies by sea, out of which 77% are functioning through the Strait of Malacca, a possible bottleneck for China [7]. There are some factors like China’s regional disputes, pirate incidences, and geopolitics that make the Strait of Malacca as an attentive weakness for China and may stop economic development in case of any unanticipated events [8, 9]. About 60% of world pirate occurrences take place in the Strait of Malacca and presence of the Indian and US armadas in the seaway rises serious security concerns and in case of any unforeseen actions can affect trade and economic supplies of China [10–12]. To overcome these challenges, China wants to get access to deep water through Pakistan. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor will link the city of Kashgar in Western China and the Gwadar Port in Pakistan by developing a transport infrastructure network comprising road and rail. Kashgar has great economic opportunities for the shortest land access to the local markets of Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, India, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan [13].

May 9, 2021

Riaz Haq

2,000-Year-Old #Buddhist #Temple Unearthed in #Swat Valley, #Pakistan. Barikot appears in classical Greek and Latin texts as “Bazira” or “Beira.” #Archaeology https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/2000-year-old-buddhist-te...

The structure is one of the oldest of its kind in the Gandhara region

Archaeologists in northwest Pakistan’s Swat Valley have unearthed a roughly 2,000-year-old Buddhist temple that could be one of the oldest in the country, reports the Hindustan Times.

Located in the town of Barikot, the structure likely dates to the second century B.C.E., according to a statement. It was built atop an earlier Buddhist temple dated to as early as the third century B.C.E.—within a few hundred years of the death of Buddhism’s founder, Siddhartha Gautama, between 563 and 483 B.C.E., reports Tom Metcalfe for Live Science.

Luca Maria Olivieri, an archaeologist at Ca’ Foscari University in Venice, led the dig in partnership with the International Association for Mediterranean and Oriental Studies (ISMEO). The excavation site is in the historical region of Gandhara, which Encyclopedia Britannica describes as “a trade crossroads and cultural meeting place between India, Central Asia and the Middle East.” Hindu, Buddhist and Indo-Greek rulers seized control of Gandhara at different points throughout the first millennium B.C.E., notes Deutsche Presse-Agentur (DPA).

The temple’s ruins stand around ten feet tall; they consist of a ceremonial platform that was once topped by a stupa, or dome often found on Buddhist shrines. At its peak, the temple boasted a smaller stupa at the front, a room or cell for monks, the podium of a column or pillar, a staircase, vestibule rooms, and a public courtyard that overlooked a road.

“The discovery of a great religious monument created at the time of the Indo-Greek kingdom testifies that this was an important and ancient center for cult and pilgrimage,” says Olivieri in the statement. “At that time, Swat already was a sacred land for Buddhism.”

In addition to the temple, the team unearthed coins, jewelry, statues, seals, pottery fragments and other ancient artifacts. Per the statement, the temple was likely abandoned in the third century C.E. following an earthquake.

Barikot appears in classical Greek and Latin texts as “Bazira” or “Beira.” Previous research suggests the town was active as early as 327 B.C.E., around the time that Alexander the Great invaded modern-day Pakistan and India. Because Barikot’s microclimate supports the harvest of grain and rice twice each year, the Macedonian leader relied on the town as a “breadbasket” of sorts, according to the statement.

Shortly after his death in 323, Alexander’s conquered territories were divided up among his generals. Around this time, Gandhara reverted back to Indian rule under the Mauryan Empire, which lasted from about 321 to 185 B.C.E.

Italian archaeologists have been digging in the Swat Valley since 1955. Since then, excavations in Barikot have revealed two other Buddhist sanctuaries along a road that connected the city center to the gates. The finds led the researchers to speculate that that they’d found a “street of temples,” the statement notes.

According to Live Science, Buddhism had gained traction in Gandhara by the reign of Menander I, around 150 B.C.E., but may have been practiced solely by the elite. Swat eventually emerged as a sacred Buddhist center under the Kushan Empire (30 to 400 C.E.), which stretched from Afghanistan to Pakistan and into northern India. At the time, Gandhara was known for its Greco-Buddhist style of art, which rendered Buddhist subjects with Greek techniques.

Feb 16, 2022

Riaz Haq

What the Iranian scholar Albiruni said about Hindus, echoed centuries later by Vivekananda

In this excerpt from his book ‘Dharma’, Chaturvedi Badrinath examines the first ever dialogue between Islamic and Hindu thought.

https://scroll.in/article/938208/what-the-iranian-scholar-albiruni-...

Albiruni's observations on Hindus:

The Hindus believe that there is no country but theirs, no nation like theirs, no kings like theirs, no religion like theirs, no science like theirs. They are haughty, foolishly vain, self-conceited, and stolid. They are by nature niggardly in communicating that which they know, and they take the greatest possible care to withhold it from men of another caste among their own people, still much more, of course, from any foreigner. According to their belief, there is no other country on earth but theirs, no other race of man but theirs, and no created beings besides them have any knowledge or science whatsoever...

...all their fanaticism is directed against those who do not belong to them – against all foreigners. They call them mlechha, ie impure, and forbid any connection with them, be it by intermarriage or any other kind of relationship, or by sitting, eating, and drinking with them, because thereby, they think, they would be polluted.

---------

The earliest, indeed the very first, dialogue between a Muslim scientist and Hindu thought took place when Albiruni (971-1039) arrived in India in the second decade of the eleventh century in circumstances that were rather ironical. He came as a camp follower of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni (967-1030). Whereas the chief purpose of Sultan Mahmud, the king of Ghazni, was to plunder the immense wealth in the form of gold and money at some of the more famous Hindu temples, the sole aim of Albiruni was to gain from the immense riches of Indian philosophies and the sciences.

That was probably also the time when Indian sciences had, on the whole, no longer anything of theoretical importance to add to their earlier great achievements. The most creative period of science in India was over by a century or two, perhaps. None of the sources Albiruni mentions in his Ta’rikh-ul-Hind was contemporary.

Aug 19, 2022