PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

India lost 6.8 million salaried jobs and 3.5 million entrepreneurs in November alone. Many among the unemployed can no longer afford to buy food, causing a significant spike in hunger. The country's economy is finding it hard to recover from COVID waves and lockdowns, according to data from multiple sources. At the same time, the Indian government has reported an 8.4% jump in economic growth in the July-to-September period compared with a contraction of 7.4% for the same period a year earlier. This raises the following questions: Has India had jobless growth? Or its GDP figures are fudged? If the Indian economy fails to deliver for the common man, will Prime Minister Narendra Modi step up his anti-Pakistan and anti-Muslim rhetoric to maintain his popularity among Hindus?

|

| Labor Participation Rate in India. Source: CMIE |

Unemployment Crisis:

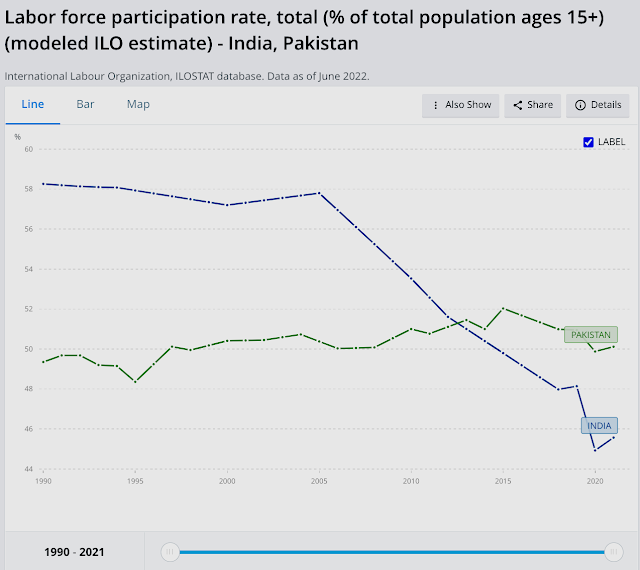

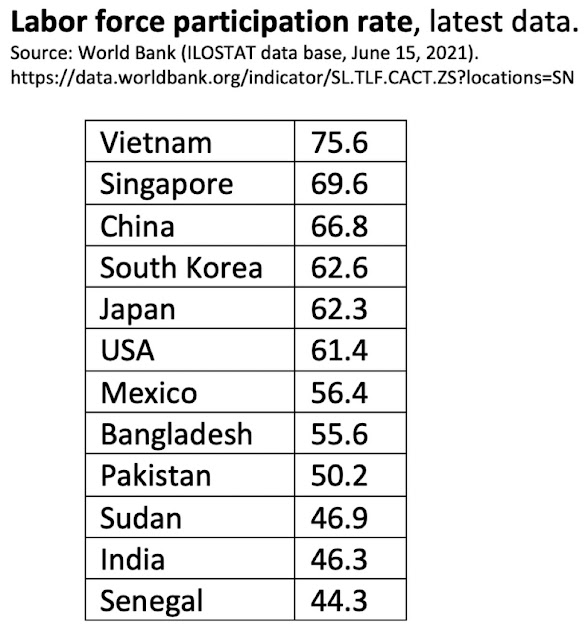

India lost 6.8 million salaried jobs and its labor participation rate (LPR) slipped from 40.41% to 40.15% in November, 2021, according to the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). In addition to the loss of salaried jobs, the number of entrepreneurs in India declined by 3.5 million. India's labor participation rate of 40.15% is lower than Pakistan's 48%. Here's an except of the latest CMIE report:

"India’s LPR is much lower than global levels. According to the World Bank, the modelled ILO estimate for the world in 2020 was 58.6 per cent (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.ZS). The same model places India’s LPR at 46 per cent. India is a large country and its low LPR drags down the world LPR as well. Implicitly, most other countries have a much higher LPR than the world average. According to the World Bank’s modelled ILO estimates, there are only 17 countries worse than India on LPR. Most of these are middle-eastern countries. These are countries such as Jordan, Yemen, Algeria, Iraq, Iran, Egypt, Syria, Senegal and Lebanon. Some of these countries are oil-rich and others are unfortunately mired in civil strife. India neither has the privileges of oil-rich countries nor the civil disturbances that could keep the LPR low. Yet, it suffers an LPR that is as low as seen in these countries".

|

| Labor Participation Rates in India and Pakistan. Source: World Bank/ILO |

|

| Labor Participation Rates for Selected Nations. Source: World Bank/ILO |

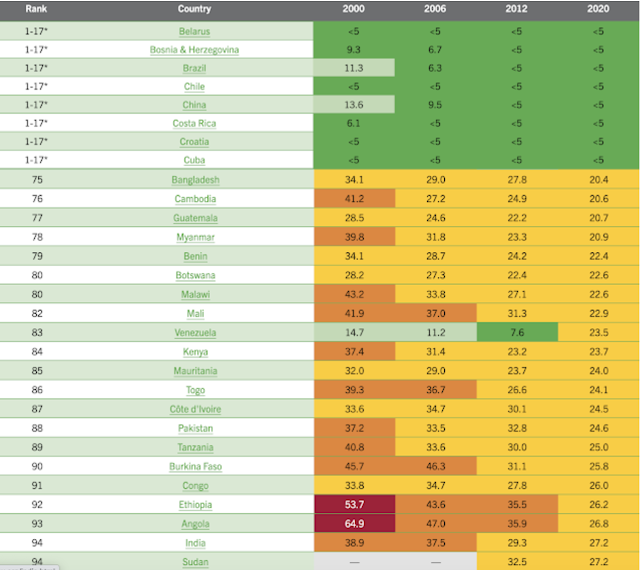

Youth unemployment for ages15-24 in India is 24.9%, the highest in South Asia region. It is 14.8% in Bangladesh 14.8% and 9.2% in Pakistan, according to the International Labor Organization and the World Bank.

|

| Youth Unemployment in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. Source: ILO, WB |

In spite of the headline GDP growth figures highlighted by the Indian and world media, the fact is that it has been jobless growth. The labor participation rate (LPR) in India has been falling for more than a decade. The LPR in India has been below Pakistan's for several years, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO).

|

| Indian GDP Sectoral Contribution Trend. Source: Ashoka Mody |

|

| Indian Employment Trends By Sector. Source: CMIE Via Business Standard |

|

| World Hunger Rankings 2020. Source: World Hunger Index Report |

Hunger and malnutrition are worsening in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia because of the coronavirus pandemic, especially in low-income communities or those already stricken by continued conflict.

India has performed particularly poorly because of one of the world's strictest lockdowns imposed by Prime Minister Modi to contain the spread of the virus.

Hanke Annual Misery Index:

Pakistan's Real GDP:

Vehicles and home appliance ownership data analyzed by Dr. Jawaid Abdul Ghani of Karachi School of Business Leadership suggests that the officially reported GDP significantly understates Pakistan's actual GDP. Indeed, many economists believe that Pakistan’s economy is at least double the size that is officially reported in the government's Economic Surveys. The GDP has not been rebased in more than a decade. It was last rebased in 2005-6 while India’s was rebased in 2011 and Bangladesh’s in 2013. Just rebasing the Pakistani economy will result in at least 50% increase in official GDP. A research paper by economists Ali Kemal and Ahmad Waqar Qasim of PIDE (Pakistan Institute of Development Economics) estimated in 2012 that the Pakistani economy’s size then was around $400 billion. All they did was look at the consumption data to reach their conclusion. They used the data reported in regular PSLM (Pakistan Social and Living Standard Measurements) surveys on actual living standards. They found that a huge chunk of the country's economy is undocumented.

Pakistan's service sector which contributes more than 50% of the country's GDP is mostly cash-based and least documented. There is a lot of currency in circulation. According to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), the currency in circulation has increased to Rs. 7.4 trillion by the end of the financial year 2020-21, up from Rs 6.7 trillion in the last financial year, a double-digit growth of 10.4% year-on-year. Currency in circulation (CIC), as percent of M2 money supply and currency-to-deposit ratio, has been increasing over the last few years. The CIC/M2 ratio is now close to 30%. The average CIC/M2 ratio in FY18-21 was measured at 28%, up from 22% in FY10-15. This 1.2 trillion rupee increase could have generated undocumented GDP of Rs 3.1 trillion at the historic velocity of 2.6, according to a report in The Business Recorder. In comparison to Bangladesh (CIC/M2 at 13%), Pakistan’s cash economy is double the size. Even a casual observer can see that the living standards in Pakistan are higher than those in Bangladesh and India.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

Indian Economy Grew Just 0.2% Annually in Last Two Years

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

Pakistan's 2012 GDP Estimated at $401 Billion

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid19 Crisis

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Counterparts

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan Fares Marginally Better Than India On Disease Burdens

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

COVID Lockdown Decimates India's Middle Class

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

How Has India Built Large Forex Reserves Despite Perennial Trade Deficits

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

Riaz Haq

Weakness In India's Economy Is Showing In Quarterly Corporate Earnings - Bloomberg

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-11-04/india-market-buz...

It's raining earnings downgrades as economy slows

Read more at: https://www.ndtvprofit.com/markets/india-inc-faces-mounting-earning...

This is the highest proportion since early 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic upended economic activity for months. Jefferies now forecasts that the earnings of Nifty companies will grow at just 10% in the year ending March.

India Inc. Faces Mounting Earnings Downgrades As Growth Slowdown Weighs Jefferies has cut fiscal 2025 earnings estimates for over 60% of the 98 companies it covers which reported second quarter earnings.

Global brokerage firm Jefferies has cut fiscal 2025 earnings estimates for over 60% of the 98 companies it covers which reported second quarter earnings. This is so far the highest downgrade ratio since early 2020, Jefferies said in a note on Oct. 30. "Above normal rains and weak government spending has impacted earnings outcomes," Jefferies said. A clear trend should emerge in the December quarter

For the 98 September 2024 quarter results that Jefferies analysed from their coverage universe, earnings downgrades (63%) were more than earnings upgrades (32%). Meaningful earnings per share downgrades were seen in most cement, oil & lending financials, mid-caps, auto and consumer staples players, it said.

The rising downgrades come as a result of a slowing economy with companies facing severe pressure from weakening urban demand. In recent post-earnings commentaries, heads of these companies have rued the slowing consumption of essentials such as food and shampoo to cars and bikes. Contrary to the Reserve Bank of India's optimistic forecast, Nomura Global Markets Research believes that India's economy

"This is probably the worst earnings cycle that we have seen going into Diwali in a long, long time," according to Rahul Arora, chief executive officer at Nirmal Bang Institutional Equities "What is very evident is that the rural economy is in a mess." Hindustan Unilever Ltd. coming with 2–3% volume growth, a low number from two-wheeler manufacturers, and even certain consumer discretionary company

Nov 4, 2024

Riaz Haq

Here's why India's shiny new metros are just costly white elephants | India News - Business Standard

https://www.business-standard.com/india-news/here-s-why-india-s-shi...

By Mihir S Sharma

Above ground, New Delhi is one of the world’s most unwelcoming capitals. Traffic is chaotic, air quality abysmal, and the crowds overwhelming. Underground is a different story: The Delhi Metro’s air-conditioned efficiency makes you feel like you’re in a completely different city.

It is easy to understand why everyone in India now wants a similar system. The government announced this month that 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) of metro lines have been built across the country. This is indeed remarkable, given that Indian towns have long struggled to build world-class public infrastructure. But the Delhi Metro is now one of the longest in the world — only Moscow, London and New York have larger networks outside mainland China — and 22 other Indian cities have metros in various stages of completion. Authorities promise that another 1,000 kilometers will be finished soon.

---

What went wrong? Everyone has different answers. The parliamentary committee that oversees urban development argues that the problem is last-mile connectivity: If you leave a metro station, you can’t connect to buses or any other form of public transport. They are 21st-century islands, cut off from their host towns’ 20th-century infrastructure.

The government’s official auditor, meanwhile, says some were built too soon, years or decades before they were needed. Yet others point out that a focus on getting metros to too many cities works against expanding any one of them — and only when a network reaches a certain minimum threshold does ridership take off. If there are too few stations, or trains don’t come often enough, it’s hard to get riders to switch modes.

Even the Delhi Metro, in my experience, is hard to switch to. From my study window, I can see elevated trains pulling into my local station less than 150 meters away, and there’s a direct line from there to my workplace. But the stations themselves are so badly designed — vast, concrete monstrosities squatting above the roads, with oddly placed entrances – that trudging from my door to the platform takes 20 minutes. In that much time I could hail an electric three-wheeler and get to work, paying just over twice the metro fare.

The Delhi Metro has succeeded because it isn’t really a metro. Its stations are far apart, unlike other systems worldwide where people can hop in and out to make quick journeys across town. It works because it functions as the suburban rail connection the city never had. People can get into the big city in comfort from the endless satellite townships that have sprung up in the dusty plains around the capital.

Some metropolises — Kolkata and Mumbai — have working light or suburban rail. Most were built pre-independence, and haven’t been updated in decades. Other, newer urban centers never had a suburban rail network at all, even as their populations exploded. The real lesson from Delhi is that India needs better local train services, not shiny new metros.

---------

The costs are beginning to add up. More than 40 per cent of India’s urban development budget is being spent on metros, according to parliament; that’s money that could be spent on new electric bus networks or charging stations for three-wheelers.

In general, India’s the opposite of China: If Beijing built too much infrastructure, New Delhi built too little. But the flashy new metro systems in smaller cities are an exception. Their empty, expensive carriages and echoing stations are the nation’s white elephants, and one day the bill will come due.

Jan 30, 2025

Riaz Haq

@javedhassan

Ashoka Mody’s article is a model of clarity: sharp, jargon-free, and unflinching in exposing how flawed statistics distort India’s economic reality and undermine democratic accountability.

Three key takeaways:

1. India’s reported GDP growth is substantially overstated due to methodological flaws, especially poor measurement of the unorganised sector (∼90% of employment) and persistent large discrepancies between income and expenditure estimates. Adjusting for these would reduce the past decade’s average growth to modest levels, far below the “fastest-growing major economy” claim.

2. The jobs crisis is severe but hidden: low official unemployment masks widespread underemployment, stagnant real wages, and reliance on low-productivity informal work. Mass consumption is weak, increasingly driven by a narrow elite importing luxury goods, while rental and living costs erode purchasing power for most.

3. Most seriously for democracy, misleading data allow governments to proclaim success amid mass distress, depriving citizens of the factual basis to hold power accountable. When statistics cease to reflect lived experience, democracy itself is weakened—a warning that extends beyond India.

Mody’s lucid linkage of technical critique to political consequence is outstanding. This is not just an Indian story; it is a warning for any country trying to manufacture flattering numbers as substitute to honest assessment of citizens’ welfare.

https://x.com/javedhassan/status/2013425545908805632?s=20

----------

Democracy damned by doctored data

When growth numbers flatter power, hide job scarcity, and mute rising costs, bad data stops disciplining policy and democracy pays a hefty price.

Ashoka Mody

https://frontline.thehindu.com/economy/india-gdp-growth-myth-data-i...

India’s GDP growth in the second quarter of 2025-26 (8.2 per cent) was greeted with the familiar ritual of celebration. A Bloomberg columnist described it as “growth that the world envies.” It did not matter that, nearly simultaneously, tucked away as Appendix VII of its Article IV report (the annual health check) for India, the International Monetary Fund gave India’s GDP estimation process a C grade. Translation: Indian GDP is poorly measured. Yet, the IMF—without a hint of irony and with no reference to its own data critique—stipulates in the main body of the report: “Real GDP growth has remained robust following a strong post-pandemic recovery.”

We have a problem, one that is systemic and corrosive. This is no longer just about GDP; it is about an India dominated by elite power, reinforced by resurgent nationalism and a media that has subordinated itself to an assertive official vision of the country. Global elites have their own geopolitical reasons for applauding the Indian narrative.

All of India’s macroeconomic data—GDP, employment, and prices—are seriously flawed. India scores a C in all categories the IMF covers, except trade data, which are difficult to fudge or spin. Curated use of flawed data feeds a seductive storyline: India, soon a developed nation; a superpower, perhaps.

Even these flawed data, read carefully, reveal a consistently sobering reality. The GDP data bear a clear signature of the breathtaking lifestyles of India’s rich—driving a surge of import-intensive consumption. The flip side is weak consumption of mass consumer goods, echoed in waning domestic investment. The reason for this suppressed demand is also clear: much-publicised low unemployment rates and understated inflation conceal the scarcity of dignified jobs and the daily struggles of ordinary people. Meanwhile, the narrative of a glorious India flatters elite vanity while leaving both the economy and democracy exposed to peril.

2 hours ago