PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

India lost 6.8 million salaried jobs and 3.5 million entrepreneurs in November alone. Many among the unemployed can no longer afford to buy food, causing a significant spike in hunger. The country's economy is finding it hard to recover from COVID waves and lockdowns, according to data from multiple sources. At the same time, the Indian government has reported an 8.4% jump in economic growth in the July-to-September period compared with a contraction of 7.4% for the same period a year earlier. This raises the following questions: Has India had jobless growth? Or its GDP figures are fudged? If the Indian economy fails to deliver for the common man, will Prime Minister Narendra Modi step up his anti-Pakistan and anti-Muslim rhetoric to maintain his popularity among Hindus?

|

| Labor Participation Rate in India. Source: CMIE |

Unemployment Crisis:

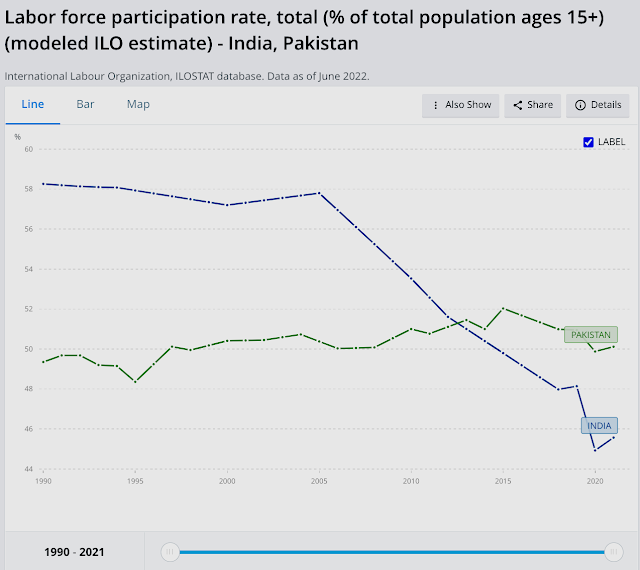

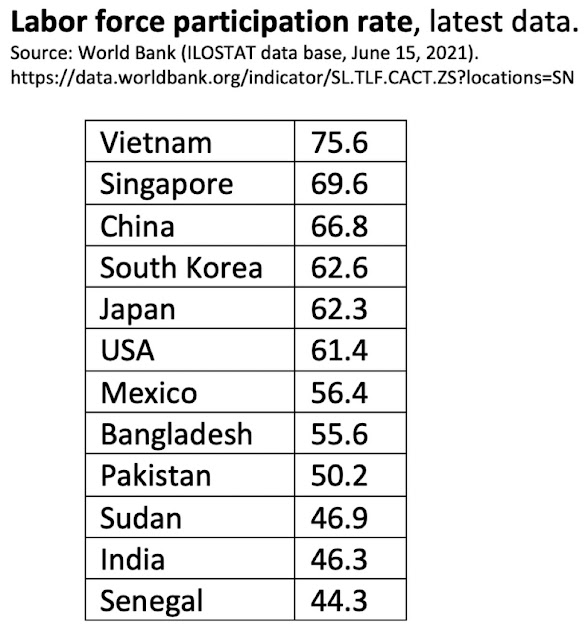

India lost 6.8 million salaried jobs and its labor participation rate (LPR) slipped from 40.41% to 40.15% in November, 2021, according to the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). In addition to the loss of salaried jobs, the number of entrepreneurs in India declined by 3.5 million. India's labor participation rate of 40.15% is lower than Pakistan's 48%. Here's an except of the latest CMIE report:

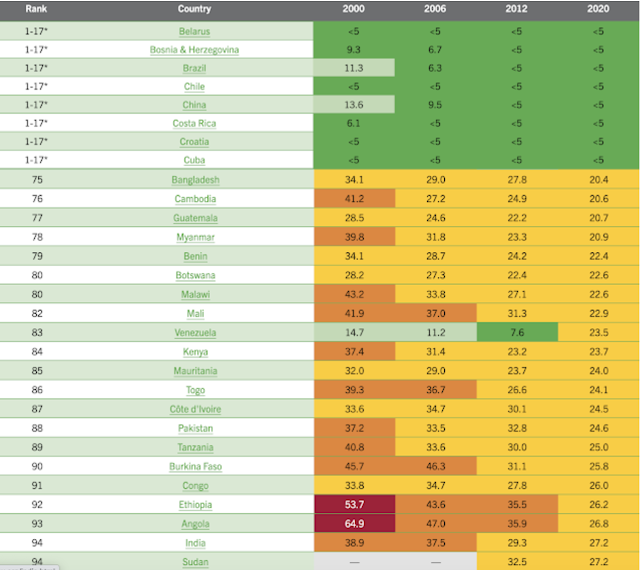

"India’s LPR is much lower than global levels. According to the World Bank, the modelled ILO estimate for the world in 2020 was 58.6 per cent (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.ZS). The same model places India’s LPR at 46 per cent. India is a large country and its low LPR drags down the world LPR as well. Implicitly, most other countries have a much higher LPR than the world average. According to the World Bank’s modelled ILO estimates, there are only 17 countries worse than India on LPR. Most of these are middle-eastern countries. These are countries such as Jordan, Yemen, Algeria, Iraq, Iran, Egypt, Syria, Senegal and Lebanon. Some of these countries are oil-rich and others are unfortunately mired in civil strife. India neither has the privileges of oil-rich countries nor the civil disturbances that could keep the LPR low. Yet, it suffers an LPR that is as low as seen in these countries".

|

| Labor Participation Rates in India and Pakistan. Source: World Bank/ILO |

|

| Labor Participation Rates for Selected Nations. Source: World Bank/ILO |

Youth unemployment for ages15-24 in India is 24.9%, the highest in South Asia region. It is 14.8% in Bangladesh 14.8% and 9.2% in Pakistan, according to the International Labor Organization and the World Bank.

|

| Youth Unemployment in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. Source: ILO, WB |

In spite of the headline GDP growth figures highlighted by the Indian and world media, the fact is that it has been jobless growth. The labor participation rate (LPR) in India has been falling for more than a decade. The LPR in India has been below Pakistan's for several years, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO).

|

| Indian GDP Sectoral Contribution Trend. Source: Ashoka Mody |

|

| Indian Employment Trends By Sector. Source: CMIE Via Business Standard |

|

| World Hunger Rankings 2020. Source: World Hunger Index Report |

Hunger and malnutrition are worsening in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia because of the coronavirus pandemic, especially in low-income communities or those already stricken by continued conflict.

India has performed particularly poorly because of one of the world's strictest lockdowns imposed by Prime Minister Modi to contain the spread of the virus.

Hanke Annual Misery Index:

Pakistan's Real GDP:

Vehicles and home appliance ownership data analyzed by Dr. Jawaid Abdul Ghani of Karachi School of Business Leadership suggests that the officially reported GDP significantly understates Pakistan's actual GDP. Indeed, many economists believe that Pakistan’s economy is at least double the size that is officially reported in the government's Economic Surveys. The GDP has not been rebased in more than a decade. It was last rebased in 2005-6 while India’s was rebased in 2011 and Bangladesh’s in 2013. Just rebasing the Pakistani economy will result in at least 50% increase in official GDP. A research paper by economists Ali Kemal and Ahmad Waqar Qasim of PIDE (Pakistan Institute of Development Economics) estimated in 2012 that the Pakistani economy’s size then was around $400 billion. All they did was look at the consumption data to reach their conclusion. They used the data reported in regular PSLM (Pakistan Social and Living Standard Measurements) surveys on actual living standards. They found that a huge chunk of the country's economy is undocumented.

Pakistan's service sector which contributes more than 50% of the country's GDP is mostly cash-based and least documented. There is a lot of currency in circulation. According to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), the currency in circulation has increased to Rs. 7.4 trillion by the end of the financial year 2020-21, up from Rs 6.7 trillion in the last financial year, a double-digit growth of 10.4% year-on-year. Currency in circulation (CIC), as percent of M2 money supply and currency-to-deposit ratio, has been increasing over the last few years. The CIC/M2 ratio is now close to 30%. The average CIC/M2 ratio in FY18-21 was measured at 28%, up from 22% in FY10-15. This 1.2 trillion rupee increase could have generated undocumented GDP of Rs 3.1 trillion at the historic velocity of 2.6, according to a report in The Business Recorder. In comparison to Bangladesh (CIC/M2 at 13%), Pakistan’s cash economy is double the size. Even a casual observer can see that the living standards in Pakistan are higher than those in Bangladesh and India.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

Indian Economy Grew Just 0.2% Annually in Last Two Years

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

Pakistan's 2012 GDP Estimated at $401 Billion

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid19 Crisis

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Counterparts

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan Fares Marginally Better Than India On Disease Burdens

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

COVID Lockdown Decimates India's Middle Class

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

How Has India Built Large Forex Reserves Despite Perennial Trade Deficits

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

Riaz Haq

India needs to jump-start manufacturing. Here’s how to do it.

By Dhiraj Nayyar

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/11/24/modi-india-econo...

India is notorious for missing geopolitical opportunities — but this time might be different. In contrast to his predecessors, who mostly hailed from the agricultural heartland of North India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi comes from the western coastal state of Gujarat, which has long given priority to manufacturing. In Gujarat, manufacturing contributes 30 percent to the state’s GDP, a level comparable to China’s.

Having served as chief minister of Gujarat for nearly 13 years before he became prime minister, Modi is acutely aware of what manufacturing needs to thrive. Since he became prime minister in 2014, Modi has tried to make life easier for businesses by cutting regulations and incentivizing bureaucrats to speed up approval processes. Now, in his second term in office, he is going further by embracing industrial policy.

India’s long history of failed state intervention has made politicians wary of industrial policy. Yet in recent years, as manufacturing continues to lag, Modi has opted to intervene. His production-linked incentives program is designed to reward domestic and foreign-owned firms across 13 chosen sectors, from automobiles to pharma to advanced batteries. The aim is to ensure global competitiveness by achieving greater scale in production. The program is set to distribute about $25 billion to industry over four years.

The second intervention is his program for manufacturing semiconductor and display factories, which offers up to $10 billion in the form of capital subsidy to potential investors. (Disclosure: My company, Vedanta, has applied for subsidies from this program as part of its investment in a semiconductor and display manufacturing joint venture with Taiwan’s Foxconn.) Interestingly, the subsidy program was announced before Congress passed its Chips and Science Act this year.

Modi’s embrace of industrial policy is a gamble — but it might be India’s best hope. Subsidies on their own won’t be enough. Success depends on whether the Indian manufacturing sector can prove its ability to compete in global markets. That will likely require a whole host of other structural reforms — a huge challenge in India’s noisy democracy, where a multitude of vested interests complicates the withdrawal of protections and unproductive subsidies. This will require all of Modi’s considerable political skills (and perhaps a third term in office starting in 2024).

But the country’s manufacturers have no time to waste. Right now, firms exiting China are looking for other options. India needs to do everything to ensure it is the first choice.

Nov 25, 2022

Riaz Haq

Aakar Patel

@Aakar__Patel

manufacturing share of gdp has fallen after launch of make in india

a report by ashoka ceda’s ankur bhardwaj showed jobs in manufacturing in india had halved after 2017

the beauty of new india is that popularity is dissociated from performance/governance

https://twitter.com/Aakar__Patel/status/1596395004733202432?s=20&am...

---------------

CEDA-CMIE Bulletin No 4: May 2021

With the second wave of the coronavirus pandemic battering India at present, the Indian economic outlook looks bleak for the second year in a row. In 2020-21, India’s real GDP growth is estimated to be minus 8%. This would also put pressure on India’s employment numbers. In previous bulletins, we have analyzed the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on employment, individual and household incomesand expenditures in 2020.

In this CEDA-CMIE Bulletin, we try to take a longer-term view of sector-wise employment in India. We base this on CMIE’s monthly time-series of employment by industry going back to the year 2016. For this bulletin, we have focused on seven sectors, viz. agriculture, mines, manufacturing, real estate and construction, financial services, non-financial services, and public administrative services. These sectors make up for 99% of total employment in the country.

https://ceda.ashoka.edu.in/ceda-cmie-bulletin-manufacturing-employm...

Nov 26, 2022

Riaz Haq

How Modi Led India Into a COVID Catastrophe - World News

India's excess deaths during pandemic up to 4.9 mln, study ...

Burning Trains Reveal Wrath of Millions Without Jobs in India

Role Of Agriculture In Indian Economy 2022 - Know All Facts

India GDP sector-wise 2021 - StatisticsTimes.com

https://statisticstimes.com/economy/country/india-gdp-sectorwise.php

Dec 6, 2022

Riaz Haq

India Can’t Dethrone China as the World’s Manufacturing Power

https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/india-can%E2%80%99t-dethrone...

Due to its insufficient labor quality and infrastructure investment, fractured society, market restrictions, and trade protectionism, the South Asian nation is unlikely to replace China.

With everything seemingly going right for India, can it really replace China on the global supply chain? Unfortunately for India, due to its insufficient labor quality and infrastructure investment, fractured society, market restrictions, and trade protectionism, the South Asian nation is unlikely to replace China in the global manufacturing supply chain anytime soon.

To begin with, India’s labor quality and infrastructure availability fall far behind China’s. Many people consider India’s low labor costs a key advantage vis-à-vis China. Indeed, India’s daily median income in urban areas in 2017 was $4.21, roughly sixteen years behind China’s, which was $12.64. However, what good are low labor costs if the benefits are also relatively low? Despite India’s laudable development achievements in the past few decades, its capability enhancements have lagged far behind China’s. India’s share of stunted children today is roughly the same as China’s over two decades ago, its life-expectancy growth is twenty-five years behind China’s, and its adult literacy rate is roughly three decades behind.

Not to mention, India’s state capacity is less extensive than China’s, and many Indians who grow up in slums live their entire lives without government files. Therefore, India’s lag in labor capability enhancement behind China is likely worse than what official data suggest. These factors affect workers’ efficiency on factory floors and their ability to advance their careers in manufacturing over the long term. Low labor costs might not make up for these low labor qualities. In fact, if India cannot deal with these capability deficits effectively, its surging population might undermine India’s social stability, although the Modi administration has done well so far in this respect.

Besides labor, manufacturing also requires capital, especially infrastructure. Few developing countries can compete with China in this regard, and India is no exception. To be clear, when foreign investors chose China to be their manufacturing hub, it was, to a certain extent, a coincidence. In 1994, China reformed its tax system to enhance the central government’s control over the country’s fiscal revenues. The reform forced local governments to look for new sources of tax income and ultimately resort to local government financing vehicles (LGFVs). Because the land appreciation tax went to local governments, they began to encourage construction, sell rights to land use, and use tracts of land as collateral to fund infrastructure in the form of LGFVs. The LGFVs led to an abundance of investments and many empty industrial parks. When Western investors started to look overseas for places to build factories around the same period, China seemed especially appealing due to its availability of capital.

-------

Despite its many advantages and Western countries’ support, it is unlikely that India can replace China in the global manufacturing supply chain for the foreseeable future. Economically, despite its low labor costs, the low quality of India’s labor pool that stems from its deficits in capability development offset its labor advantages, and inadequate infrastructure investments put India at a disadvantage regarding capital costs. Socially, India’s fractured multi-dimensional society creates different economic demands for various groups, undermining the advantages of India’s large population. Politically, India’s market restrictions make its business environment less favorable and decrease its industrial labor supply. Meanwhile, protectionist traditions hinder India’s ability to adopt an export-oriented growth model and integrate itself into the global supply chain.

Dec 11, 2022

Riaz Haq

In mid-April, India is forecast to surpass China as the world's most populous country.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-63957562

It could, for example, strengthen India's claim of getting a permanent seat in the UN Security Council, which has five permanent members, including China.

India is a founding member of the UN and has always insisted that its claim to a permanent seat is just. "I think you have certain claims on things [by being the country with largest population]," says John Wilmoth, director of the Population Division of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

The way India's demography is changing is also significant, according to KS James of the Mumbai-based International Institute for Population Sciences.

Despite drawbacks, India deserves some credit for managing a "healthy demographic transition" by using family planning in a democracy which was both poor and largely uneducated, says Mr James. "Most countries did this after they had achieved higher literacy and living standards."

More good news. One in five people below 25 years in the world is from India and 47% of Indians are below the age of 25. Two-thirds of Indians were born after India liberalised its economy in the early 1990s. This group of young Indians have some unique characteristics, says Shruti Rajagopalan, an economist, in a new paper. "This generation of young Indians will be the largest consumer and labour source in the knowledge and network goods economy. Indians will be the largest pool of global talent," she says.

India needs to create enough jobs for its young working age population to reap a demographic dividend. But only 40% of of India's working-age population works or wants to work, according to Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE).

More women would need jobs as they spend less time in their working age giving birth and looking after children. The picture here is bleaker: only 10% of working-age women were participating in the labour force in October, according to CMIE, compared with 69% in China.

Then there's migration. Some 200 million Indians have migrated within the country - between states and districts - and their numbers are bound to grow. Most are workers who leave villages for cities to find work. "Our cities will grow as migration increases because of lack of jobs and low wages in villages. Can they provide migrants a reasonable living standard? Otherwise, we will end up with more slums and disease," says S Irudaya Rajan, a migration expert at Kerala's International Institute of Migration and Development.

Demographers say India also needs to stop child marriages, prevent early marriages and properly register births and deaths. A skewed sex ratio at birth - meaning more boys are born than girls - remains a worry. Political rhetoric about "population control" appears to be targeted at Muslims, the country's largest minority when, in reality, "gaps in childbearing between India's religious groups are generally much smaller than they used to be", according to a study from Pew Research Center.

And then there's the ageing of India

Demographers say the ageing of India receives little attention.

In 1947, India's median age was 21. A paltry 5% of people were above the age of 60. Today, the median age is over 28, and more than 10% of Indians are over 60 years. Southern states such as Kerala and Tamil Nadu achieved replacement levels at least 20 years ago.

"As the working-age population declines, supporting an older population will become a growing burden on the government's resources," says Rukmini S, author of Whole Numbers and Half Truths: What Data Can and Cannot Tell Us About Modern India.

"Family structures will have to be recast and elderly persons living alone will become an increasing source of concern," she says.

Dec 23, 2022

Riaz Haq

Indian economy grew 8.7% in last fiscal year to surpass pre-Covid levels, IMF says

Growth expected to moderate to 6.8% in current year amid tighter financial conditions

https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/economy/2022/12/23/indian-...

India’s real gross domestic product grew by 8.7 per cent in the 2021-2022 fiscal year, boosting its total output above pre-coronavirus levels despite global macroeconomic headwinds, the International Monetary Fund has said.

India, Asia's third-largest economy and the world's fifth largest, rebounded from the deep pandemic-induced downturn on the back of fiscal measures to address high prices and monetary policy tightening to address elevated inflation, the Washington-based lender said in a report on Friday.

“Economic headwinds include inflation pressures, tighter global financial conditions, the fallout from the war in Ukraine and associated sanctions on Russia, and significantly slower growth in China and advanced economies,” the fund said.

“Growth has continued this fiscal year, supported by a recovery in the labour market and increasing credit to the private sector.”

In October, the IMF cut its global economic growth forecast for next year, amid the Ukraine conflict, broadening inflation pressures and a slowdown in China, the world’s second-largest economy.

The fund maintained its global economic estimate for this year at 3.2 per cent but downgraded next year's forecast to 2.7 per cent — 0.2 percentage points lower than its July forecast.

There is a 25 per cent probability that growth could fall below 2 per cent next year, the IMF said in its World Economic Outlook report at the time.

Global economic growth in 2023 is expected to be as weak as in 2009 during the financial crisis as a result of the Ukraine conflict and its impact on the world economy, according to the Institute of International Finance.

Economic growth in India is expected to moderate, reflecting the less favourable outlook and tighter financial conditions, the IMF said.

Real GDP is projected to grow at 6.8 per cent for the current financial year to the end of March, and by 6.1 per cent in 2023-2024 fiscal year, according to the fund's estimates.

Reflecting broad-based price pressures, inflation in India is forecast at 6.9 per cent in the 2022-2023 fiscal year and expected to moderate only gradually over the next year.

Rising inflation can further dampen domestic demand and affect vulnerable groups, according to the fund.

India’s current account deficit is expected to increase to 3.5 per cent of GDP in the 2022-2023 fiscal year as a result of both higher commodity prices and strengthening import demand, the lender said.

“A sharp global growth slowdown in the near term would affect India through trade and financial channels,” it said.

“Intensifying spillovers from the war in Ukraine can cause disruptions in the global food and energy markets, with significant impact on India. Over the medium term, reduced international co-operation can further disrupt trade and increase financial markets’ volatility.”

However, the successful introduction of wide-ranging reforms or greater-than-expected dividends from the advances in digitalisation could increase India’s medium-term growth potential, the IMF said.

Additional monetary tightening should be carefully calibrated and communicated, it said.

“The exchange rate should act as the main shock absorber, with intervention limited to address disorderly market conditions,” the report said.

The IMF also recommended that India’s financial sector policies should continue to support the exit of non-viable companies and encourage banks to build capital buffers and recognise problem loans.

Reforms to strengthen governance and reduce the government’s footprint are needed to support strong medium-term growth, it said.

The lender also highlighted the need for structural reforms to promote resilient, green and inclusive growth.

Dec 24, 2022

Riaz Haq

#Indian #Railways: The #job-seekers tricked into counting #trains. The men believed they were training for a job with the Indian Railways. #Employment #SCAM https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-64093555

Police in India's capital Delhi are investigating a complaint about a job fraud in which around 28 men were tricked into counting trains for days.

The men believed they were training for a job with the Indian Railways.

A former army official, who said he unknowingly put the men in contact with the alleged scammers, alerted the police about the fraud.

The victims paid between 200,000 rupees ($2,400; £2,000) and 2.4m rupees each to get the job, local media reported.

The Delhi police's economic offences wing started investigating the alleged scam in November but the news became public only last week.

The men, who are from the southern Tamil Nadu state, were asked to stand at different platforms of the main railway station in Delhi for eight hours every day for about a month. There, they counted the trains that passed through the station every day, news agency Press Trust of India reported.

The men were promised they would be hired as ticket examiners, traffic assistants or clerks in the railways, one of India's largest employers.

One of the victims told The Indian Express newspaper that he had been looking for ways to support his family after the Covid-19 pandemic.

"We went to Delhi for training - all we had to do was count trains. We were sceptical of the activity, but the accused was a good friend of our neighbour. I feel ashamed now," he said.

Subbuswamy, the former army man who filed the complaint with the police, told PTI that he had been helping young men from his hometown in Tamil Nadu Virudhunagar district find jobs "without any monetary interest" for himself.

He said he met a person called Sivaraman who claimed to have connections with lawmakers and ministers and offered to find government jobs for the unemployed men.

He then put Subbuswamy and the victims in touch with another man, who even took the candidates for fake medical examinations. The man later stopped answering phone calls from them.

Some of the victims said they borrowed money to pay the scammers.

Scams for government jobs are often reported in India, where millions of young people are desperate for stable, secure employment. In March 2021, police in the southern Hyderabad city said they had arrested two men believed to have tricked around a hundred candidates who thought they were being hired by the railways.

Dec 26, 2022

Riaz Haq

India's Unemployment Rate For December Is 8.3%, A 16-Month High: Report

https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/indias-unemployment-rate-for-decemb...

Mahesh Vyas, managing director of CMIE, said this is "not as bad as it may seem" as it came on top of a healthy increase in the labour participation rate

India's unemployment rate rose to 8.3 per cent in December, the highest in 16 months, from 8 per cent in the previous month, data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) showed today.

The urban unemployment rate rose to 10.09 per cent in December from 8.96 per cent in the previous month, while rural unemployment rate slipped to 7.44 per cent from 7.55 per cent, the data showed.

Mahesh Vyas, managing director of the CMIE, said the rise in the unemployment rate was "not as bad as it may seem" as it came on top of a healthy increase in the labour participation rate, which shot up to 40.48 per cent in December, the highest in 12 months.

"Most importantly, the employment rate has increased in December to 37.1 per cent, which again is the highest since January 2022," he told Reuters.

Containing high inflation and creating jobs for millions of young people entering the job market remain the biggest challenge for Prime Minister Narendra Modi's administration ahead of national elections in 2024.

The main opposition Congress launched a march in September from the Kanyakumari to Srinagar to mobilise public opinion on issues such as high prices, unemployment and what it says are the "divisive politics" of the BJP.

"India needs to move from a single focus on GDP growth to growth with employment, skilling of youth and creating production capacities with export prospects," Congress leader Rahul Gandhi, who is leading the 3,500-km march on foot, told reporters yesterday.

The unemployment rate had declined to 7.2 per cent in the July-September quarter compared to 7.6 per cent in the previous quarter, according to separate quarterly data compiled by National Statistical Office (NSO) and released in November.

In December, the unemployment rate rose to 37.4 per cent in Haryana, followed by 28.5 per cent in Rajasthan and 20.8 per cent in Delhi, CMIE data showed.

Jan 1, 2023

Riaz Haq

India’s latest organised job scam episode has affected people in the Indian states of Gujarat, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal, and Odisha. They were duped of crores of rupees after being promised jobs, reports said.

“The scam was being run by a group of tech-savvy engineers from Uttar Pradesh with the help of some expert website developers. This core group was assisted by around 50 call center employees. These employees were paid 15,000 rupees ($181) per month and were from Jamalpur and Aligarh localities of Uttar Pradesh,” according to Jai Narayan Pankaj, a senior Odisha police officer.

Candidates paid up to Rs70,000 for training and other orientation programmes, including Rs3,000 in registration fees. However, the training never happened, Pankaj said.

In another incident unearthed in December, around 30 people were tricked into counting the arrival and departure of trains at the New Delhi Railway Station for a month, BBC reported. They were told this was part of their training for the positions of travel ticket examiner, traffic assistant, and clerk. Each of the duped candidates had paid up between Rs2 lakh and Rs24 lakh for the coveted Indian Railways job.

Scammers are not limited to operating within India’s borders either. Some work through agents even in Dubai and Bangkok. Aspirants are sometimes persuaded to move to countries like Thailand. Many are taken illegally to Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia where they are held captive and forced into cybercrime.

India is just not creating enough jobs

In September and October, India added over 8.5 million jobs in the formal sector. However, that was not enough, considering the number of applicants, along with fresh graduates, exceeded the number of available jobs.

In December, India’s unemployment rate rose to 8.3%, the highest in 16 months, data from the Mumbai-based Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) showed.

datawrapper-chart-z6nHe

Worsening this is the global inflationary pressure and fears of an impending recession, sparking layoffs in recent months. This is besides the enduring effects of the pandemic years.

“One of the alarming possibilities for India...is the fact that our additions to the labour workforce are likely to slow down as it happened in China or in Europe and other developed economies,” TeamLease Services co-founder Rituparna Chakraborty told The Indian Express newspaper.

A study by CMIE and the Centre of Economic Data and Analysis of Ashoka University showed that over 12.5 million people aged 15-29 years not only lost jobs in 2020 but also stopped looking for new ones.

The number of farm jobs, meanwhile, increased during this time but that only underscored the economy’s weakness, the study found.

Jan 3, 2023

Riaz Haq

The year 2023 marks a historic turning point for Asia's demography: For the first time in the modern era, India is projected to surpass China as the most populous country.

https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Asia-Insight/Old-Japan-young-Indi...

Besides China (1.426 billion) and India (1.417 billion), five other Asian countries had over 100 million people as of 2022, the U.N. figures show. Indonesia had 276 million, Pakistan's population was at 236 million, Bangladesh counted 171 million, Japan had 124 million and the Philippines had 116 million. Vietnam, with 98 million, is expected to join the club soon.

------------

Even though economists expect India's gross domestic product to grow around 7% in 2023 -- the highest among major economies -- and although the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic appears to be over, India continues to face high unemployment rates of around 8%, according to the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy, a local private researcher. That shows the country is not creating enough jobs to support the growing population.

---------

Kumagai also said that India's growing demand for food could be felt beyond its borders.

"The challenge for India concerning food is that the production of agricultural products is easily affected by the weather," he said. "On the other hand, domestic demand is increasing rapidly. As such, when production is low, domestic supply is prioritized, which eventually may lead to restrictions on exports, just as India restricted wheat exports in 2022, which could cause food problems in other countries as well."

--------

While the South Asian nation's growing and youthful population spells opportunities for development, it also creates layers of challenges, from poverty reduction to education. Experts say soaring demand for food could affect India's trade with other countries, while the World Bank recently estimated that India will need to invest $840 billion into urban infrastructure over the next 15 years to support its swelling citizenry.

"This is likely to put additional pressure on the already stretched urban infrastructure and services of Indian cities -- with more demand for clean drinking water, reliable power supply, efficient and safe road transport amongst others," the bank's report said.

India's dilemmas are only part of a complex and diverging Asian population picture -- split between young, growing countries and aging, declining ones. Humanity's latest milestone turns a spotlight on this gap and the problems on both sides of it.

---

Reaching a world of 8 billion people signals significant improvements in public health that have increased life expectancy, the U.N. said. But it also pointed out, "The world is more demographically diverse than ever before, with countries facing starkly different population trends ranging from growth to decline."

Nowhere is this more apparent than in Asia. The region has young countries with a median age in the 20s, such as India (27.9 years old), Pakistan (20.4) and the Philippines (24.7), as well as old economies with median ages in the 40s, including Japan (48.7) and South Korea (43.9). The gap between the young and the old has gradually widened over the past decades.

While India faces a lack of jobs and infrastructure to support its growing population, Japan faces a serious reduction in births, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which its government says is a "critical situation." Either way, the population trends are increasingly impacting economies and societies.

Even though economists expect India's gross domestic product to grow around 7% in 2023 -- the highest among major economies -- and although the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic appears to be over, India continues to face high unemployment rates of around 8%, according to the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy, a local private researcher. That shows the country is not creating enough jobs to support the growing population.

Jan 3, 2023

Riaz Haq

The Sardar family was eligible for 35 kilos of rice and grain monthly from a government-run aid programme but had been approved for just two kilos because they lacked the right ID documents, according to Paul. “They had been without even these minimal benefits for six months,” she told The New Humanitarian.

Sunil Agarwala, the district magistrate of Jhargram, refuted the allegations, telling The Hindu newspaper they were "baseless", while insisting that Sardar’s death “was due to illness, TB, and other reasons”.

According to the World Health Organization, undernutrition is a key driver of TB, while malnutrition also makes TB therapy less effective and raises the risk of TB-related death.

The recently published Medical Certification Cause of Death (MCCD), 2020 report found that fewer than a quarter of the 81,15,882 registered deaths in India that year had known causes. Hunger activists are alarmed that a country with 1.4 billion people can only verify the causes of 22.5% of its documented fatalities.

Swati Narayan, assistant professor at the School for Public Health and Human Development at O.P. Jindal Global University, told The New Humanitarian that medical workers are unlikely to catch if the cause of death is starvation given how post-mortems are typically carried out.

She said it was crucial to also consider the person's socioeconomic position and the condition of their body, including the weight of their organs, visceral fat, and diseases brought on by a weaker immune system and malnutrition.

“The post-mortem reports are not an accurate reflection of hunger or starvation deaths in the country,” Narayan said. “Oral autopsies are much better at determining if the cause of death was hunger.”

Worsening hunger and the fight for a stronger safety net

Question marks around Sardar’s death and others like it – a similar case involving three “hunger deaths” in the same family went before the high court last month in Jharkhand, which borders West Bengal to the east – come amid signs of growing food insecurity in India.

The 2022 Global Hunger Index ranks India at 107 out of 121 nations, six places lower than its previous ranking, and below the likes of Ethiopia, Bangladesh, and Pakistan.

While India remains in the “serious” category rather than “alarming” or “very alarming”, it recorded the highest percentage (19.3%) of any country of children under five who are “wasting”, meaning they’re below average weight for their height.

The pandemic made hunger worse, but income losses and rising debt continued to drive it up long after the worst of the health crisis had passed. A survey by the Right to Food Campaign in late 2021/early 2022 found that nearly 80% of respondents faced food insecurity, and almost half had run out of food the previous month.

However, the hunger problems also pre-date COVID. India’s last National Family Health Survey, which used data from 2019, found that stunting – a sign of chronic malnutrition – had risen in 11 out of the 17 states. In 13 states, wasting had also increased.

Jan 3, 2023

Riaz Haq

India’s economy is growing at the fastest pace of any major country, fueled by corporate earnings and middle-class consumption of the sorts of goods these companies (delivery companies) are rushing to deliver.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/04/business/india-delivery-apps.html

But there has been no commensurate growth in steady jobs in India’s deeply unequal society. That has left the legions of working poor who toil as delivery drivers to serve a middle class that they have fewer and fewer hopes of ever entering.

Millions have been pushed into gig work as Prime Minister Narendra Modi has moved to privatize public entities and cut red tape, enacting a series of changes to labor regulations that have diluted protections for workers.

The number of gig workers is projected to reach 23.5 million in 2030, nearly triple the number in 2020, according to a June report by Niti Aayog, a government research agency.

With India’s public sector shrinking, the informal sector now accounts for more than nine out of 10 jobs, International Labor Organization data show. Such jobs, without guaranteed health insurance, social security or pensions, range from the treacherous — construction work without hard hats or other protective gear, or assembly-line labor in illegal firetrap factories — to the merely miserable.

Work as a delivery driver can seem a better alternative. Delivery app companies dangle offers of 45,000 rupees per month, or more than $540, in targeted ads on social media, about double the country’s median income.

But drivers say they rarely earn anything close. What they do get is constant hounding by customers and automated calls from the companies to go faster. The algorithms that assign orders, they say, reward drivers with high ratings, which are based on the speed and number of past deliveries. Drivers say delays — regardless of the reason — can mean a reduction in assignments or even a suspension, pressure that sometimes pushes drivers to put themselves in danger.

Mr. Niralwar joins other delivery app drivers every evening as they mill about in a dusty, unpaved parking area in Hyderabad. They chat between orders, lifting pant legs to compare motorcycle injuries.

Ankit Bhatt, 33, moved to Hyderabad four years ago so that his wife could take a job at a call center. Without a college degree, he had more limited employment options: low-paying retail or informal manual labor.

Ready to begin his evening shift for Swiggy Instamart, Mr. Bhatt tried to log in but found that his ID had been temporarily blocked — punishment, he said, for failing to deliver an order after his motorcycle clutch had given out.

“You could be sick, you could have an accident, your bike could have mechanical issues. You will be penalized for that,” Mr. Bhatt said.

Jan 4, 2023

Riaz Haq

Why Does #Modi Not Want #India's #Census2021? Would it Expose #BJP's Lies About Progress in Open Defecation, Village #Electrification, #Poverty, #Hunger?? https://www.economist.com/asia/2023/01/05/postponing-indias-census-...

Narendra Modi often overstates his achievements. For example, the Hindu-nationalist prime minister’s claim that all Indian villages have been electrified on his watch glosses over the definition: only public buildings and 10% of households need a connection for the village to count as such. And three years after Mr Modi declared India “open-defecation free”, millions of villagers are still purging al fresco. An absence of up-to-date census information makes it harder to check such inflated claims. It is also a disaster for the vast array of policymaking reliant on solid population and development data.

----------

Three years ago India’s government was scheduled to pose its citizens a long list of basic but important questions. How many people live in your house? What is it made of? Do you have a toilet? A car? An internet connection? The answers would refresh data from the country’s previous census in 2011, which, given India’s rapid development, were wildly out of date. Because of India’s covid-19 lockdown, however, the questions were never asked.

Almost three years later, and though India has officially left the pandemic behind, there has been no attempt to reschedule the decennial census. It may not happen until after parliamentary elections in 2024, or at all. Opposition politicians and development experts smell a rat.

----------

For a while policymakers can tide themselves over with estimates, but eventually these need to be corrected with accurate numbers. “Right now we’re relying on data from the 2011 census, but we know our results will be off by a lot because things have changed so much since then,” says Pronab Sen, a former chairman of the National Statistical Commission who works on the household-consumption survey. And bad data lead to bad policy. A study in 2020 estimated that some 100m people may have missed out on food aid to which they were entitled because the distribution system uses decade-old numbers.

Similarly, it is important to know how many children live in an area before building schools and hiring teachers. The educational misfiring caused by the absence of such knowledge is particularly acute in fast-growing cities such as Delhi or Bangalore, says Narayanan Unni, who is advising the government on the census. “We basically don’t know how many people live in these places now, so proper planning for public services is really hard.”

The home ministry, which is in charge of the census, continues to blame its postponement on the pandemic, most recently in response to a parliamentary question on December 13th. It said the delay would continue “until further orders”, giving no time-frame for a resumption of data-gathering. Many statisticians and social scientists are mystified by this explanation: it is over a year since India resumed holding elections and other big political events.

Jan 7, 2023

Riaz Haq

The Squeeze on India’s Spenders Is Yet to Lift

Analysis by Andy Mukherjee | Bloomberg

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/the-squeeze-onindias-spende...

Manufacturing of wants is hard anywhere for marketers, but the challenge is bigger when the bottom half of the population takes home only 13% of national income. While India’s rapid economic growth since the 1990s has undoubtedly expanded the spending capacity of its 1.4 billion people, acute and rising inequality — among the worst in the world — makes for a notoriously budget-conscious median consumer. Companies can take nothing for granted: For Unilever’s local Indian unit, a late winter crimped sales of skin-care products last quarter.

Still, the maker of Dove body wash and Surf detergent managed to eke out an overall 5% increase in sales volume from a year earlier, lifting net income to 25.1 billion rupees ($309 million), slightly better than expected. That was achieved by price cuts — passing along the benefit of lower palm-oil costs to soap buyers — and a step up in promotion and advertising. Still, not all players have the market leader’s financial chops. Investors who look closely at Hindustan Unilever Ltd.’s earnings for a pulse on India’s consumer demand will note with dismay the slide in industry-wide volumes for cleaning liquids, personal care items and food, the categories in which the firm competes.

This isn’t new. Consumer demand in India has been moderating since August 2021. Village households, many of which had to liquidate their gold holdings and other assets to treat Covid-19 patients during that summer’s lethal delta outbreak, were not in a mood to spend even after the surge in deaths and hospitalization ebbed.

Then, as major economies began to open up and crude oil and other commodities began to get pricier, firms like Unilever responded to the squeeze by reducing how much they put in a pack. Their idea was to hold on to psychologically crucial “magic price points” — such as five or 10 rupees — in the hope that customers will replenish more often. But when inflation accelerated after the start of the war in Ukraine, there was no option except to shatter the illusion of affordability by raising prices. Volumes flat-lined in the March quarter.

“The worst of inflation is behind us,” Sanjiv Mehta, the chief executive officer, said in a statement after last week’s earnings report. That seems to be the case indeed. India’s aggregate price index rose a slower-than-expected 5.7% in December, the third straight month of cooling. That’s why perhaps instead of pushing four 100-gram bars of Lux soap for 140 rupees, Unilever is charging 156 rupees for five, according to the Business Standard. In offering an 11% price cut by bulking up pack sizes, the company is betting that most households’ budget can now accommodate an extra outlay of 16 rupees.

It’s a reasonable gamble. A bumper wheat harvest is expected this spring. Rural India, which employs two out of three workers, found jobs for a disproportionately larger share of new entrants to the labor force in November and December, according to Mahesh Vyas of CMIE, a private firm that fills in for reliable official jobs data. “Most of the additional employment is happening in rural India and not in the towns,” he says.

And that may well put the spotlight next year on faltering spending in cities. The tech industry is wobbling globally. In India, too, startups are firing employees in large numbers; some former darlings of venture capital, such as online test-prep and education firms, are becoming irrelevant now that Covid-19 restrictions on physical classes have ended.

Meanwhile, India’s software-exports industry — a large employer in metropolises — has become wary of hiring because of slowing global growth. “The pain in urban consumption seems to be showing up,” JM Financial analysts Richard Liu and others wrote last week after Asian Paints Ltd.’s earnings.

Jan 22, 2023

Riaz Haq

Two-wheeler volumes drop to FY 10/12 levels. Huge drop in entry level Motorcycle sales indicate pain in rural/semi-urban areas. Experts say at least 50% capacity lying idle at two-wheeler factories.

Point to deeply worrying economic realities.

#India 2-Wheeler Sales Volume Declines to 2012 Level: 12.2 Million in 2022. Capacity utilization down to 50%. #Modi #MakeInIndia #Manufacturing #Unempolyment #economy https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/auto/bikes/two-wheeler-market-s...

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/auto/bikes/two-wheeler-market-s...

https://twitter.com/haqsmusings/status/1619198354780733441?s=20&...

Jan 27, 2023

Riaz Haq

#India, soon world's most populous nation, doesn't know how many people it has. Critics of PM #Modi have accused his gov’t of delaying the census to hide data on politically sensitive issues, such as #unemployment, ahead of national #elections due in 2024.

https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-soon-worlds-most-populous...

Experts say the delay in updating data like employment, housing, literacy levels, migration patterns and infant mortality, which are captured by the census, affects social and economic planning and policy making in the huge Asian economy.

Calling census data "indispensable", Rachna Sharma, a fellow at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, said studies like the consumption expenditure survey and the periodic labour force survey are estimations based on information from the census.

"In the absence of latest census data, the estimations are based on data that is one decade old and is likely to provide estimates that are far from reality," Sharma said.

A senior official at the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation said census data from 2011, when the count was last conducted, was being used for projections and estimates required to assess government spending.

A spokesman for the ministry said its role was limited to providing the best possible projections and could not comment on the census process. The Prime Minister's Office did not respond to requests for comment

Two other government officials, one from the federal home (interior) ministry and another from the office of the Registrar General of India, said the delay was largely due to the government's decision to fine-tune the census process and make it foolproof with the help of technology.

The home ministry official said the software that will be used to gather census data on a mobile phone app has to be synchronised with existing identity databases, including the national identity card, called Aadhaar, which was taking time.

The office of the Registrar General of India, which is responsible for the census, did not respond to a request for comment.

The main opposition Congress party and critics of Prime Minister Narendra Modi have accused the government of delaying the census to hide data on politically sensitive issues, such as unemployment, ahead of national elections due in 2024.

"This government has often displayed its open rivalry with data," said Congress spokesperson Pawan Khera. "On important matters like employment, Covid deaths etc., we have seen how the Modi government has preferred to cloak critical data.”

The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party's national spokesperson, Gopal Krishna Agarwal, dismissed the criticism.

"I want to know on what basis they are saying this. Which is the social parameter on which our performance in nine years is worse than their 65 years?" he said, referring to the Congress party's years in power.

TEACHERS' TRAVAILS

The United Nations has projected India's population could touch 1,425,775,850 on April 14, overtaking China on that day.

The 2011 census had put India's population at 1.21 billion, meaning the country has added 210 million, or almost the number of people in Brazil, to its population in 12 years.

India's census is conducted by about 330,000 government school teachers who first go door-to-door listing all houses across the country and then return to them with a second list of questions.

They ask more than two dozen questions each time in 16 languages in the two phases that will be spread over 11 months, according to the plan made for 2021.

The numbers will be tabulated and final data made public months later. The entire exercise was estimated to cost 87.5 billion rupees ($1.05 billion) in 2019.

Feb 14, 2023

Riaz Haq

India’s economic activity cooled off at the start of the year as higher borrowing costs tempered demand at home and abroad, signaling more pain ahead as the global economy slows down.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-02-19/india-s-economic...

The needle on a dial measuring so-called animal spirits moved left and was back where it was for six straight months before showing momentum in December. Falling exports and a slack in manufacturing and services drove the weakness in business activity, offsetting improvement in consumption drivers reflected by tax collections and job growth, according to eight high-frequency indicators tracked by Bloomberg.

Domestic recovery, that has been driving momentum so far, is getting wobbly. The Reserve Bank of India, which has raised borrowing costs six times since May to 6.50 per cent, is seen increasing interest rates again in its April review amid inflation topping estimates and further tightening by global central banks.

Bloomberg’s animal spirits barometer uses a three-month weighted average to smooth out volatility in single-month readings:

Business Activity

Purchasing managers’ surveys indicated activity in both manufacturing and services slacked in January. Output and new orders grew at softer paces, and dragged the composite index lower from an 11-year high in December.

“Although manufacturers received new orders from international markets, the increase was slight at best and moderated considerably to a ten-month low,” said Pollyanna De Lima, economics associate director at S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Exports

Exports fell 6.58 per cent in January from a year ago to US$32.9 billion (S$43.9 billion), data released by the Trade Ministry showed, indicating lower demand for goods abroad. Imports dropped 3.63 per cent from a year earlier and that pushed the trade gap to the lowest in a year, fueling hopes of a significantly narrower current account deficit.

The sharp fall in imports reflects the moderation in discretionary demand in the goods sector and the decline in commodity prices, said Garima Kapoor, economist at Elara Capital.

Consumer Activity

Liquidity in the banking system tightened, but credit growth picked up again, rising 16.33% in January, from 14.87 per cent in December, Reserve Bank of India data show.

Goods and services tax collections, which help measure consumption in the economy, rose 10.5 per cent from a year earlier to 1.56 trillion rupees – a feat achieved only once before in the history of the levy introduced in 2017. New vehicle registrations surged 14 per cent in the month, with passenger vehicle sales growing 22 per cent year-on-year, according to data from the Federation of Automobile Dealers Associations.

Market Sentiment

Electricity consumption, a widely used proxy to gauge demand in the industrial and manufacturing sectors, held steady, with the peak requirement last month rising to 173 gigawatt from 171 gigawatt in December due to increased heating requirements. India’s unemployment rate dropped to 7.14 per cent, from a 16-month high of 8.30 per cent a month ago, according to data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy. BLOOMBERG

Feb 19, 2023

Riaz Haq

Is India’s boom helping the poor?

What vehicle sales reveal about the country’s growth

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/03/02/is-india...

In a land where labour is cheap, the man who drives the most luxury cars is not a billionaire. He is a parking attendant. On a meagre salary, he must park, double-park and triple-park cars in tight spaces, and then extricate them. In India, where car sales have increased by 16% since the start of the covid-19 pandemic—a trend partly driven by the growing popularity of hefty sports-utility vehicles—this tricky job is becoming even more difficult.

To many, India’s automobile boom symbolises the country’s superfast economic rise. On February 28th new figures revealed that India’s gdp grew by 4.4% year on year in the last quarter of 2022, down from 6.3% in the previous quarter. Despite the slowdown, the imf expects India to be the fastest-growing major economy in 2023, and to account for 15% of global growth. The governing Bharatiya Janata Party (bjp) believes the country is in the midst of Amrit Kaal, an auspicious period that will bring prosperity to all Indians.

Not everyone is convinced by the bjp’s boosterism. To sceptics, rising vehicle sales in fact demonstrate the unsavoury lopsidedness of India’s economic growth. Indeed, purchases of two-wheelers, such as scooters and motorcycles, have sputtered since covid hit, and are down by 15% since 2019. These are the vehicles of the masses: half of households own a two-wheeler; fewer than one in ten own a car.

Not many questions are more central to Indian politics than the wellbeing of the country’s everyman. The problem is that answering the question is fraught with difficulty. Official statistics are patchy. Ministers have not published a poverty estimate in more than a decade. Thus assessments and inferences must be made using other surveys and data sets, such as vehicle sales.

These suggest poverty reduction has stalled, and maybe even reversed. According to a survey of 44,000 households by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (cmie), a research outfit, only 6% of India’s poorest households—those bringing in less than 100,000 rupees ($1,200) a year—believe their families are better off than a year ago. The recovery from the pandemic, when harsh lockdowns whacked the economy, has been horribly slow.

The World Bank estimates shutdowns pushed 56m Indians into extreme poverty. Since then inflation has further eroded purchasing power: real wages in rural areas, where most of the poor live, have stagnated, and annual inflation jumped to 6.5% in January. Poor families, for whom food makes up 60% of household expenditure, have felt the strongest pinch. Rural food costs have risen by 28% since 2019; onion prices by an eye-watering 51%.

Labour-market data also bely India’s impressive headline growth figures. Take-up for a rural-employment programme, which guarantees low-wage work to participants, remains above pre-covid levels. cmie surveys suggest the unemployment rate is also higher, averaging more than 7% over the past two years. Many people have given up looking: labour-force participation rates have fallen since the pandemic.

There are plenty of problems with India’s economy, from poor primary education to an inability to grow its limited manufacturing sector. But these were present even as previous growth spurts lifted millions out of poverty. Recent pains are thus more likely to reflect the pandemic’s after-effects. Construction firms in cities, for example, complain of labour shortages, as many workers who headed to villages during lockdowns have not yet returned.

These may at last be starting to ease. The latest data releases suggest that rural wages may be picking up. Deposits in bank accounts set up for the poor are also rising. Even sales of two-wheelers are slowly creeping up. A lot more improvement will be needed, however, for claims of Amrit Kaal to ring true.

Mar 3, 2023

Riaz Haq

"India is Broken" writes Princeton Economist Ashoka Modi. Says #Indians, mostly illiterate and poor, hunger for freedom and prosperity but their politicians from #Nehru to #Modi have “betrayed the economic aspirations” of millions. #BJP https://www.wsj.com/articles/india-is-broken-review-the-difficult-f... via @WSJBooks

Ashoka Mody, who was for many years a senior economist at the International Monetary Fund, is the sort of quietly efficient global technocrat who retires to a professorship at a prestigious school—in his case, Princeton. Yet he’s different from his faceless ilk of briefcase-bearers in one astonishing way: 13 years ago, an attempt was made on his life. The alleged assailant, thought to have been passed over for a job at the IMF by Mr. Mody, shot him in the jaw outside his house in Maryland.

He recovered with remarkable verve, his intellectual drive intact. Yet a mood of gloom and pessimism is unmistakable in “India Is Broken.” Today, 75 years after independence from Britain, Mr. Mody believes that India’s democracy and economy are in a state of profound malfunction. The book’s tale, he writes, “is one of continuous erosion of social norms and decay of political accountability.” You might add that it is also a tale of an audacious political experiment on the brink of failure.

India started its post-independence journey, says Mr. Mody, as “an improbable democracy” whose citizens, mostly illiterate and poor, hungered for freedom and prosperity. Generations of Indian politicians—from Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister, to Narendra Modi, the present one—have “betrayed the economic aspirations” of millions. India’s democracy no longer protects fundamental rights and freedoms in a nation over which “a blanket of violence” has fallen. A belief in “equality, tolerance and shared progress” has disappeared. And the country’s collapse isn’t just political and economic; it’s also moral and spiritual.

------------

A notable weakness in Mr. Mody’s analysis is his denial that the economic policies of Nehru and his successors were socialist. He writes of Nehru’s “alleged socialist legacy” and adds that it is a “mistake to identify central planning or big government as socialism.” Socialism, he insists, “means the creation of equal opportunity for all,” which India’s policy makers weren’t doing. Ergo, India wasn’t socialist.

If these protestations are almost laughable, Mr. Mody’s solution also invites some derision. Hope for India, he says, lies in making it a “true democracy.” And how can that be done? “We must move to an equilibrium in which everyone expects others to be honest.” This “honest equilibrium,” he says, will promote enough trust for Indians to work together “in the long-haul tasks of creating public goods and advancing sustainable development” and awakening “civic consciousness.” Mr. Mody, it is clear, has a dream. It is naïve, and it is corny. India, alas, will continue to be “broken” for many years to come.

Mar 4, 2023

Riaz Haq

Ex Central Bank Chief Raghu Rajan: 'India dangerously close to Hindu rate of growth'. #Hindu rate of growth is a term describing low #Indian economic growth rates from the 1950s to the 1980s, which averaged around 4%. #Modi #BJP #economy #Hindutva

https://www.deccanherald.com/business/economy-business/india-danger...

Sounding a note of caution, former Reserve Bank Governor Raghuram Rajan has said that India is "dangerously close" to the Hindu rate of growth in view of subdued private sector investment, high interest rates and slowing global growth.

Rajan said that sequential slowdown in the quarterly growth, as revealed by the latest estimate of national income released by the National Statistical Office (NSO) last month, was worrying. Hindu rate of growth is a term describing low Indian economic growth rates from the 1950s to the 1980s, which averaged around 4 per cent. The term was coined by Raj Krishna, an Indian economist, in 1978 to describe the slow growth.

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the third quarter (October-December) of the current fiscal slowed to 4.4 per cent from 6.3 per cent in the second quarter (July-September) and 13.2 per cent in the first quarter (April-June).

The growth in the third quarter of the previous financial year was 5.2 per cent. "Of course, the optimists will point to the upward revisions in past GDP numbers, but I am worried about the sequential slowdown. With the private sector unwilling to invest, the RBI still hiking rates, and global growth likely to slow later in the year, I am not sure where we find additional growth momentum," Rajan said in an email interview to PTI.

Recently, Chief Economic Advisor V Anantha Nageswaran had attributed the subdued quarterly growth to the upward revision of estimates of national income for the past years. The key question is what Indian growth will be in fiscal 2023-24, Rajan said, adding "I am worried that earlier we would be lucky if we hit 5 per cent growth. The latest October-December Indian GDP numbers (4.4 per cent on year ago and 1 per cent relative to the previous quarter) suggest slowing growth from the heady numbers in the first half of the year. "My fears were not misplaced. The RBI projects an even lower 4.2 per cent for the last quarter of this fiscal. At this point, the average annual growth of the October-December quarter relative to the to the similar pre-pandemic quarter 3 years ago is 3.7 per cent. "This is dangerously close to our old Hindu rate of growth! We must do better." The government, he said, was doing its bit on infrastructure investment but its manufacturing thrust is yet to pay dividends. The bright spot is services, he said, adding "it seems less central to government efforts." On a query regarding the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme, Rajan said any scheme in which the government pours money will create jobs and any scheme which elevates tariffs on output while offering bonuses for final units produced in India will create production in India, and exports. "A sensible evaluation would ask how many jobs are being created and at what price per job. By the government's own statistics, 15 per cent of the proposed investment has come in but only 3 per cent of the predicted jobs have been created. This does not sound like success, at least not yet," Rajan said.

Furthermore, even if the scheme fully meets the government's expectations over the next few years, it will create only 0.6 crore jobs, a small dent in the jobs India needs over the same period, the former RBI Governor said. "Similarly, government spokespersons point to the rise in cell phone exports as evidence that the scheme is working. But if we are subsidising every cell phone that is exported, this is an obvious outcome.

Mar 5, 2023

Riaz Haq

Ex Central Bank Chief Raghu Rajan: 'India dangerously close to Hindu rate of growth'. #Hindu rate of growth is a term describing low #Indian economic growth rates from the 1950s to the 1980s, which averaged around 4%. #Modi #BJP #economy #Hindutva

https://www.deccanherald.com/business/economy-business/india-danger...

Furthermore, even if the scheme fully meets the government's expectations over the next few years, it will create only 0.6 crore jobs, a small dent in the jobs India needs over the same period, the former RBI Governor said. "Similarly, government spokespersons point to the rise in cell phone exports as evidence that the scheme is working. But if we are subsidising every cell phone that is exported, this is an obvious outcome.

The key question is how much value added is done in India. It turns (out to be) very little so far," he said. Rajan said cell phone parts imports have also gone up, so net exports in the cell phone sector, the relevant measure that no one in government talks about, is pretty much where it was when the scheme started. "Except, we have also spent money on subsidies. Foxconn just announced a big factory to produce parts but they have been saying they will invest for a long time. I think we need a lot more evidence before celebrating the success of the PLI scheme," he said.

Currently, Rajan is the Katherine Dusak Miller Distinguished Service Professor of Finance at The University of Chicago Booth School of Business. He further said the most developed economies of the world are largely service economies, so you can be a large economy without a large presence in manufacturing.

"Services do not just account for the majority of our unicorns, services can also provide a lot of semi-skilled jobs in construction, transport, tourism, retail, and hospitality. So let us not deride service jobs – indeed while the fraction of manufacturing jobs has stagnated in India, services have absorbed the exodus from agriculture." "We need to work on both manufacturing and services to create the jobs we need, and fortunately, many of the inputs both (services and manufacturing) need schooling, skilling...," he said.

On what measures the government should take to improve oversight of private family companies to address worries after the Hindenburg allegations on Adani Group, Rajan said: "I don't think the issue is of more oversight over private companies". The issue is of reducing non-transparent links between government and business, and of letting, indeed encouraging, regulators do their job, he said. "Why has SEBI not yet got to the bottom of the ownership of those Mauritius funds which have been holding and trading Adani stock? Does it need help from the investigative agencies?," Rajan wondered.

Adani group has been under severe pressure since the US short-seller Hindenburg Research on January 24, accused it of accounting fraud and stock manipulation, allegations that the conglomerate has denied as "malicious", "baseless" and a "calculated attack on India".

Mar 5, 2023

Riaz Haq

Both Russia and Ukraine reported higher levels of happiness in the latest report despite the escalation of the conflict between the two countries since February 2022. According to the index, Russia’s ranking improved from 80 in 2022 to 70 this year, while Ukraine’s ranking improved from 98 to 92. The 2022 report was based on data from 2019 to 2021.

John Helliwell, one of the authors of the World Happiness Report, said that benevolence, especially acts of kindness towards strangers, increased dramatically in 2021 and remained high in 2022, CNN reported.

“Even during these difficult years, positive emotions have remained twice as prevalent as negative ones, and feelings of positive social support twice as strong as those of loneliness,” he said.

Mar 21, 2023

Riaz Haq

Hype over #India’s #economic boom is dangerous myth masking real problems. It’s built on a disingenuous numbers game.

No silver bullet that will fix weak job creation, a small, uncompetitive #manufacturing sector & gov’t schemes fattening corporate profits

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3215379/hype-over-indi...

by Ashoka Mody

Indian elites are giddy about their country’s economic prospects, and that optimism is mirrored abroad. The International Monetary Fund forecasts that India’s GDP will increase by 6.1 per cent this year and 6.8 per cent next year, making it one of the world’s fastest-growing economies.

Other international commentators have offered even more effusive forecasts, declaring the arrival of an Indian decade or even an Indian century.

In fact, India is barrelling down a perilous path. All the cheerleading is based on a disingenuous numbers game. More so than other economies, India’s yo-yoed in the three calendar years from 2020 to 2022, falling sharply twice with the emergence of Covid-19 and then bouncing back to pre-pandemic levels. Its annualised growth rate over these three years was 3.5 per cent, about the same as in the year preceding the pandemic.

Forecasts of higher future growth rates are extrapolating from the latest pandemic rebound. Yet, even with pandemic-related constraints largely in the past, the economy slowed in the second half of 2022, and that weakness has persisted this year. Describing India as a booming economy is wishful thinking clothed in bad economics.

Worse, the hype is masking a problem that has grown in the 75 years since independence: anaemic job creation. In the next decade, India will need hundreds of millions more jobs to employ those who are of working age and seeking work. This challenge is virtually insurmountable considering that the economy failed to add any net new jobs in the past decade, when 7 million to 9 million new jobseekers entered the market each year.

This demographic pressure often boils over, fuelling protests and episodic violence. In 2019, 12.5 million people applied for 35,000 job openings in the Indian railways – one job for every 357 applicants. In January 2022, railway authorities announced they were not ready to make the job offers. The applicants went on a rampage, burning train cars and vandalising railway stations.

With urban jobs scarce, tens of millions of workers returned during the pandemic to eking out meagre livelihoods in agriculture, and many have remained there. India’s already-distressed agriculture sector now employs 45 per cent of the country’s workforce.

Farming families suffer from stubbornly high underemployment, with many members sharing limited work on plots rendered steadily smaller through generational subdivision. The epidemic of farmer suicides persists. To those anxiously seeking support from rural employment-guarantee programmes, the government unconscionably delays wage payments, triggering protests.

For far too many Indians, the economy is broken. The problem lies in the country’s small and uncompetitive manufacturing sector.

Mar 30, 2023

Riaz Haq

India is Broken

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3215379/hype-over-indi...

by Ashoka Mody

Since the liberalising reforms of the mid-1980s, the manufacturing sector’s share of GDP has fallen slightly to about 14 per cent, compared to 27 per cent in China and 25 per cent in Vietnam. India commands less than a 2 per cent global share of manufactured exports, and as its economy slowed in the second half of 2022, the manufacturing sector contracted further.

Yet it is through exports of labour-intensive manufactured products that Taiwan, South Korea, China and now Vietnam came to employ vast numbers of their people. India, with its 1.4 billion people, exports about the same value of manufactured goods as Vietnam does with 100 million people.

Those who believe that India stands at the cusp of greatness usually focus on two recent developments. First, Apple contractors have made initial investments to assemble high-end iPhones in India, leading to speculation that a broader move away from China by manufacturers will benefit India despite the country’s considerable quality-control and logistical problems.

while such an outcome is possible, academic analysis and media reports are discouraging. Economist Gordon H. Hanson says Chinese manufacturers will move labour-intensive manufacturing from the country’s expensive coastal hubs to its less-developed interior, where production costs are lower.

Moreover, investors moving out of China have gone mainly to Vietnam and other countries in Southeast Asia, which like China are members of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. India has eschewed membership in this trade bloc because its manufacturers fear they will be unable to compete once other member states gain easier access to the Indian market.

As for US producers pulling away from China, most are “near-shoring” their operations to Mexico and Central America. Altogether, while some investment from this churn could flow to India, the fact remains that inward foreign investment fell year on year in 2022.

The second source of hope is the Indian government’s Production-Linked Incentive Schemes, which were introduced in early 2021 to offer financial rewards for production and jobs in sectors deemed to be of strategic value. Unfortunately, as former Reserve Bank of India governor Raghuram G. Rajan and his co-authors warn, these schemes are likely to end up merely fattening corporate profits like previous sops to manufacturers.

India’s run with start-up unicorns is also fading. The sector’s recent boomrelied on cheap funding and a surge of online purchases by a small number of customers during the pandemic. But most start-ups have dim prospects for achieving profitability in the foreseeable future. Purchases by the small customer base have slowed and funds are drying up.

Looking past the illusion created by India’s rebound from the pandemic, the country’s economic prognosis appears bleak. Rather than indulge in wishful thinking and gimmicky industrial incentives, policymakers should aim to power economic development through investments in human capital and by bringing more women into the workforce.

India’s broken state has repeatedly avoided confronting long-term challenges and now, instead of overcoming fundamental development deficits, officials are seeking silver bullets. Stoking hype about an imminent Indian century will merely perpetuate the deficits, helping neither India nor the rest of the world.

Ashoka Mody, visiting professor of international economic policy at Princeton University, is the author of India is Broken: A People Betrayed, Independence to Today. Copyright: Project Syndicate

Mar 30, 2023

Riaz Haq

Analysis: India's surging services exports may shield economy from external risks

https://www.reuters.com/world/india/indias-surging-services-exports...

IT services still accounted for 45% of India's total services exports in April-December.

Professional and management consulting grew the fastest - at a 29% compounded annual growth rate over the last three years, as per estimates by economists at HSBC Securities and Capital Markets.

The recent growth in services exports has been largely powered by global capability centres, which have started to offer global clients a range of high-end and critical solutions such as accounting and legal support.

----------------

This, together with a drop in merchandise trade deficit, resulted in the current account deficit shrinking more than expected to $18.2 billion, or 2.2% of GDP.

---------------