PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

As India and Pakistan turn 75, there are many secular intellectuals on both sides of the border who question the wisdom of "the Partition" in 1947. They dismiss what is happening in India today under Hindu Nationalist Prime Minister Narendra Modi's leadership as a temporary aberration, not the norm. They long for a return to "Indian liberalism" which according to anthropologist Sanjay Srivastava "did not exist".

|

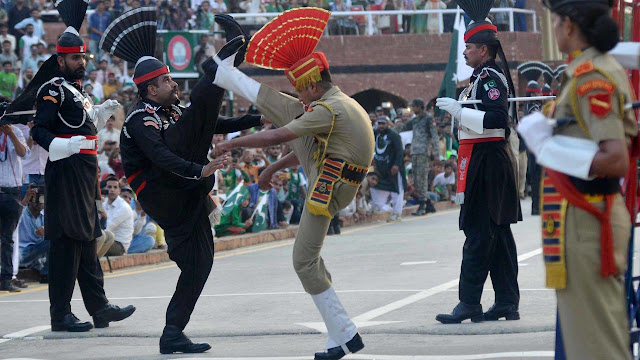

| India Pakistan Border Ceremony at Wagah-Attari Crossing |

American historian Audrey Truschke who studies India traces the early origins of Hindu Nationalism to the British colonial project to "divide and rule" the South Asian subcontinent. She says colonial-era British historians deliberately distorted the history of Indian Muslim rule to vilify Muslim rulers as part of the British policy to divide and conquer India. These misrepresentations of Muslim rule made during the British Raj appear to have been accepted as fact not just by Islamophobic Hindu Nationalists but also by at least some of the secular Hindus in India and Muslim intellectuals in present day Pakistan, says the author of "Aurangzeb: The Life and Legacy of India's Most Controversial King". Aurangzeb was neither a saint nor a villain; he was a man of his time who should be judged by the norms of his times and compared with his contemporaries, the author adds.

After nearly a century of direct rule, the British largely succeeded in dividing South Asians along religious and sectarian lines. The majoritarian tyranny of the "secular" Hindu-dominated Indian National Congress after 1937 elections in India became very apparent to Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the leader of All India Muslim League. Speaking in Lucknow in October 1937, he said the following:

"The present leadership of the Congress, especially during the last ten years, has been responsible for alienating the Musalmans of lndia more and more, by pursuing a policy which is exclusively Hindu; and since they have formed the Governments in six provinces where they are in a majority they have by their words, deeds, and programme shown more and more that the Musalmans cannot expect any justice or fair play at their hands. Whenever they are in majority and wherever it suited them, they refused to co-operate with the Muslim League Parties and demanded unconditional surrender and signing of their pledges."

Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Hindu Nationalist BJP party's appeal is the greatest among Hindus who closely associate their religious identity and the Hindi language with being “truly Indian.” The Pew survey found that less than half of Indians (46%) favored democracy as best suited to solve the country’s problems. Two percent more (48%) preferred a strong leader.

Indian anthropologist Sanjay Srivastava sums up the current situation as follows:

"Our parents practiced bigotry of a quiet sort, one that did not require the loud proclamations that are the norm now. Muslims and the lower castes knew their place and the structures of social and economic authority were not under threat. This does not necessarily translate into a tolerant generation. Rather, it was a generation whose attitudes towards religion and caste was never really tested. The loud bigotry of our times is no great break from the past in terms of a dramatic change in attitudes – is it really possible that such changes can take place in such few years? Rather, it is the crumbling of the veneer of tolerance against those who once knew their place but no longer wish to accept that position. The great problem with all this is that we continue to believe that what is happening today is simply an aberration and that we will, when the nightmare is over, return to the Utopia that was once ours. However, it isn’t possible to return to the past that was never there. It will only lead to an even darker future. And, filial affection is no antidote for it".

Disintegration of India

Dalit Death Shines Light on India's Caste Apartheid

Caste Discrimination Rampant Among Silicon Valley Indians

Rape: A Political Weapon in Modi's India

Hindutva: The Legacy of the British Rulers "Divide and Rule" Project

Will Modi's Hindutva Lead to Multiple Partitions of India?

Riaz Haq Youtube Channel

PakAlumni: Pakistani Social Network

Riaz Haq

Dr. Audrey Truschke

@AudreyTruschke

Upper-caste Hindu nationalists on this interview right now: “Googlers didn’t mind talking about caste, they just didn’t want a Dalit-led group talking about caste.”

What sheer, unadulterated bigotry.

https://twitter.com/AudreyTruschke/status/1558221459591467009?s=20&...

https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/googles-caste-bias-problem

Google’s Caste-Bias Problem

A talk about bigotry was cancelled amid accusations of reverse discrimination. Whom was the company trying to protect?

By Isaac Chotiner

https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/googles-caste-bias-problem

ntil recently, Tanuja Gupta was a senior manager at Google News. She was involved in various forms of activism at the company, and, in April, she invited Thenmozhi Soundararajan, the founder of Equality Labs, a nonprofit, to speak about the subject of caste discrimination. (India’s caste system, which has existed in some form for centuries, separates Hindus into broadly hierarchical groups that often correspond to historical religious practice and familial professions. Those at the bottom of the system are called Dalits—formerly known as “untouchables”—and still face extreme discrimination in India.)

Numerous employees within the company expressed the view that any talk on caste discrimination was offensive to them as Hindus, and made them feel unsafe. The talk was eventually cancelled, and Gupta, who had been at Google for more than ten years, resigned amid an investigation into her own behavior. (A spokesperson for Google said that it has “a very clear, publicly shared policy against retaliation and discrimination in our workplace.”)

I recently spoke with Gupta. Her lawyer, Cara Greene, joined the conversation, which we agreed would stay on the record. During the interview, which has been edited for length and clarity, we discussed how Silicon Valley deals with issues of caste discrimination, why Google employees felt “threatened” by the talk that Gupta had scheduled, and the circumstances behind her departure from the company.

Why did you want to join Google, and what did you feel about the place when you did?

tanuja gupta: I started working at Google in 2011. I had been working as a program manager in engineering and software for about a decade, but Google was top of the top. Of course you want a career at a great company. That was a product that I used day in and day out. It was a great opportunity.

When did you decide that you wanted to get involved with activism inside Google?

t.g.: Probably with the Google walkout in 2018. It was the height of the MeToo movement. The Kavanaugh confirmation was happening. The news about Andy Rubin had broken—the ninety-million-dollar payout that he received despite allegations of sexual misconduct. And so I think there was a little bit of a breaking point within the company, and in myself, the experiences that I’d had in tech. That’s when it started.

As we’ve all grown during the past couple of years, diversity, equity, and inclusion [D.E.I.] has become more and more recognized as not just a moral nicety but actually as a business imperative, that companies have a competency around these matters, especially in products. For the past three years, I was working on Google News products. To be able to cover news topics about matters of race, gender equity, caste, things like that, you actually have to be able to understand matters of diversity and inclusion. And so it went from being a separate, side thing to integral to being good at your core job.

Aug 12, 2022

Riaz Haq

What got you interested in the subject of caste discrimination?

t.g.: There was my own obvious background. My parents immigrated from India in the early nineteen-eighties. I was certainly familiar with the topic. In September, 2021, two employees approached me. I hosted D.E.I. office hours every week where people could come in and talk about these topics, confidentially, and multiple Google employees came into my office and reported that they had faced discrimination when trying to talk about matters of caste in the workplace. There was already a public condemnation of caste discrimination at Google from the Alphabet workers’ union. They had put out a press statement when the Cisco case broke. There were reports from at least twenty Google employees as well. [In June, 2020, California sued Cisco and two of its managers for engaging in caste discrimination. Afterward, Equality Labs received complaints from more than two hundred and fifty tech workers, including twenty Google employees.]

What made it really relevant to Google News was that, in 2022, there was a huge election in India where matters of caste equity were integral. Given the news-product footprint in India, caste is absolutely something we need to talk about, and we need to make sure that our products are thinking about folks from different caste backgrounds.

You’re talking about the election earlier this year, in Uttar Pradesh, which is the most populous state in India, with more than two hundred million people, where a very right-wing politician, aligned with the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, was reëlected as chief minister. [The B.J.P, led by India’s Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, is known for its defenses of Hindu identity and religious chauvinism; its base of support has typically come from privileged-caste Hindus, although under Modi the Party has made inroads among voters from a variety of castes.] Are you saying that to understand these issues of caste was important for your work, and not just for the inner harmony of your workplace?

t.g.: That’s right. It was a perfect storm of all these things—colleagues coming to me as well as our products being affected by it.

And were these colleagues coming to you in India or in the United States or both?

t.g.: Both.

Were these people who were experiencing discrimination firsthand, or was it more people who wanted to talk about this issue and why it’s important?

t.g.: The first conversations I had were with people who felt that they were being discriminated against for even raising this topic. I think that’s a form of discrimination in and of itself—where you can talk about some matters related to D.E.I. but not others. Then you had some other folks who faced it directly because of being caste oppressed.

When you say that people felt that they could not bring up caste discrimination, was this in the context of stories about what was happening in Uttar Pradesh, or things within the workplace, or both?

t.g.: Within the workplace.

Who was the discrimination coming from, and how did it manifest?

t.g.: I can share what I’ve seen and what’s been shared with me. The first thing is denial. Saying this doesn’t even exist. That is a form of discrimination. There were messages on e-mail threads that talked about how this isn’t a problem here. If you replace the denial of caste discrimination with the denial of the Holocaust or something like that, it instantly clicks where other people start to realize, “Oh, something’s wrong if people are denying this.” The second thing—and I think the Cisco case is probably the most publicly known example—is that, within a team, when you’ve got people who are caste privileged and caste oppressed, the people who are caste oppressed start to be given inferior assignments, get treated differently, left out of meetings, which are certainly things that I heard from Google employees within the company. [The Google spokesperson said that caste discrimination has “no place in our workplace and it’s prohibited in our policies.”]

Aug 12, 2022

Riaz Haq

Another thing is these coded conversations. If you’re not attuned to what the issue is, you won’t even realize what’s happening. Asking things like “What’s your last name? I’m not familiar with it.” Then, when the manager hears that last name, they’re, like, “Oh, so you’re from this caste—no wonder you have these leadership skills.” Things like that. And somebody else in the room is, like, “What the hell?” It’s those different types of experiences that I’ve seen or that have been shared with me that show that caste discrimination is happening in the workplace.

Are you saying that in the United States this discrimination is coming from other Indian Americans? This is not to say that white people or Hispanic people or Black people or whoever else can’t perpetrate caste discrimination. But I think a lot of people who aren’t aware of the caste system or do not recognize someone’s name or what that might suggest about their caste would say, “How could I discriminate about caste? I don’t even know anything about caste.”

t.g.: I don’t fault people for not knowing the intricacies of caste discrimination. I fault people for not wanting to learn about it. Willfully not wanting to learn more about certain topics when you hear that people are being discriminated against, choosing not to do anything about it, that is a problem. And that’s what was happening. People can absolutely discriminate based on caste by essentially denying it and not wanting to learn about it.

In other words, there is first-order discrimination by Indian Americans toward people from underprivileged castes. And then when this gets kicked up the chain of command or gets commented upon, people of varying backgrounds practice their own form of discrimination by not looking into it or not wanting to hear about it.

t.g.: That’s exactly right.

So, you are hearing these stories. What happens next?

t.g.: We asked a speaker to come talk to our news team about matters of caste and discrimination, and specifically caste representation in the newsroom. Two days before the talk, which is part of a larger D.E.I. programming series that I ran for the team, a number of e-mails got sent to my V.P., to the head of H.R., to our chief diversity officer, to our C.E.O. directly, claiming that the talk was creating a hostile workplace, that people felt unsafe, that the speaker was not qualified to speak on the topic, and several other allegations. The talk got postponed. That was the term that was used.

Who was sending these e-mails?

t.g.: They were all internal Google employees. That’s about as much as I can say. Google essentially decides to turn down the temperature by postponing the talk and conduct further due diligence on this speaker. Bear in mind that, just five months earlier, this speaker had spoken at Cloud Next, which is a huge event for Google Cloud.

Then nothing happened for two weeks. There was no follow-up on the due diligence, or what made the speaker objectionable in the first place. I told Google that they’d been given some misinformation, and explained why it wasn’t true, and got nothing. At that point, Dalit History Month, which is in April, was about to end.

Aug 12, 2022