PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

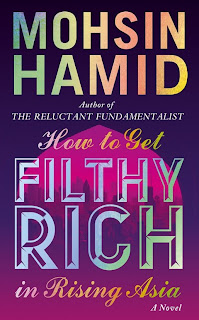

It's a story of a sickly little village boy's rise in Pakistan from abject rural poverty to great urban wealth as a young man who falls in love with "the pretty girl", an equally ambitious fellow slum-dweller in the city.

Billed as a "how-to" book, Mohsin Hamid's “How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia” draws upon trends like increasing urbanization, rising middle-class consumption, growing entrepreneurship and widespread scams to weave a fascinating tale set in Hamid's hometown of Lahore. It's also a boy-meets-girl love story that takes many twists and turns and ends with the two lovers finally living together in their twilight years.

Along the way, Hamid, himself part of a ambitious new generation of Pakistani writers making it big on the global stage, touches upon the principal character's brushes with religious conservatives, unscrupulous politicians, corrupt bureaucrats and criminal gangs. Hamid shows how the protagonist successfully navigates through it all until he himself falls victim to fraud perpetrated by his young lieutenant.

Although the book does not explicitly name the places, the descriptions suggest that it's set mostly in Lahore, Hamid's home town, and Karachi which is described as "city by the sea".

The protagonist is a third-born poor kid transplanted by his father along with his mother and siblings from his village to the city. The order of his birth permits him to go to school while his older siblings forgo schooling to work and help the family make ends meet in the city.

The protagonist drops out of the university that he was admitted to and goes from being a DVD rental delivery boy to a successful entrepreneur with a thriving bottled water business. Later, he has an arranged marriage which produces a son but he continues to think of “the pretty girl” from the slum who is trying to climb higher as a fashion model in the "city by the sea".

As the protagonist grows old, he finds himself alone, divorced from his wife, and separated from his son studying in the US. The story ends with him finding "the pretty girl", the love of his life, till death does them apart.

Hamid's latest novel is hard to put down once you start reading it. It is meant to be read cover-to-cover in one sitting. His prior internationally-acclaimed and equally attention-grabbing works include Moth Smoke and The Reluctant Fundamentalist. The Reluctant Fundamentalist made the New York Times Best Seller List. It was also short-listed for Man Booker Prize. It has been made into a movie slated for release in the United States next month.

Here's a trailer of The Reluctant Fundamentalist:

TRAILER - The Reluctant Fundamentalist from PartyLiciouS Entertainment on Vimeo.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

Do South Asian Slums Offer Hope?

Karachi Literature Festival

Urbanization in Pakistan Highest in South Asia

Pakistan Fashion Week

Upwardly Mobile Pakistan's Appetite For International Brands

Life Goes On in Pakistan

Resilient Pakistan

Pakistan's Top Fashion Models

Music Drives Coke Sales in Pakistan

Pakistani Cover Girls

Veena Malik Challenges Pakistan's Orthodoxy

PakAlumni-Pakistani Social Network

Huma Abedin Weinergate

Pakistan Media Revolution

Riaz Haq

Pakistani-American playwright Ayad Akhtar wins the prestigious Pulitzer Prize.

For a distinguished play by an American author, preferably original in its source and dealing with American life, Ten thousand dollars ($10,000).

Awarded to "Disgraced," by Ayad Akhtar, a moving play that depicts a successful corporate lawyer painfully forced to consider why he has for so long camouflaged his Pakistani Muslim heritage.

Finalists

Also nominated as finalists in this category were: "Rapture, Blister, Burn,” by Gina Gionfriddo, a searing comedy that examines the psyches of two women in midlife as they ruefully question the differing choices they have made; and "4000 Miles," by Amy Herzog, a drama that shows acute understanding of human idiosyncrasy as a spiky 91-year-old locks horns with her rudderless 21-year-old grandson who shows up at her Greenwich Village apartment after a disastrous cross-country bike trip.

http://www.pulitzer.org/citation/2013-Drama

Apr 15, 2013

Riaz Haq

Here's an excerpt of an earlier post I wrote on arts and literature growth in Pakistan:

Granta has highlighted the extraordinary work of many Pakistani artists, poets, writers, painters, photographers and musicians inspired by life in their native land.

For example, the magazine cover carries a picture of a piece of truck art by a prolific truck painter Islam Gull of Bhutta village in Karachi. Gull was born in Peshawar and moved to Karachi 22 years ago. He has been practicing his craft on buses and trucks since the age of 13, and now teaches his unique craft to young apprentices. Commissioned with the assistance of British Council in Karachi, Gull produced two chipboard panels photographed for the magazine cover.

Granta issue has articles, poems, paintings, photographs and frescoes about various aspects of life in Pakistan. It carries work by writers like Mohsin Hamid (The Reluctant Fundamentalist), Daniyal Mueenuddin (In Other Rooms, Other Wonders), Kamila Shamsie (Burnt Shadows), Mohammad Hanif (A Case of Exploding Mangoes) and Nadeem Aslam (The Wasted Vigil) who have been making waves in literary circles and winning prizes in London and New York.

In a piece titled "Mangho Pir", Fatima Bhutto highlights the plight of the Sheedi community, a disadvantaged ethnic minority of African origin who live around the shrine of their sufi saint Mangho Pir on the outskirts of Karachi.

In another piece "Pop Idols", Kamila Shamsie traces the history of Pakistani pop music as she experienced it living in Karachi, and explains how the music scene has changed with Pakistan's changing politics.

A piece "Jinnah's Portrait" by New York Times' Jane Perlez describes the wide variety of Quaid-e-Azam's portraits showing him dressed in outfits that give him either "the aura of a religious man" or show him as a "young man with full head of dark hair, an Edwardian white shirt, black jacket and tie, alert dark eyes". Perlez believes the choice of the founding father's potrait hung in the offices of various Pakistani officials and politicians reveals how they see Jinnah's vision for Pakistan.

While Granta's focus on art and literature has produced a fairly good publication depicting multi-dimensional life in Pakistan, there are apects that it has not covered. For example, Pakistan has a growing fashion industry which puts on fashion shows in major cities on a regular basis. The biggest of these is Pakistan Fashion Week held in Karachi in February. Over 30 Pakistani designers - including Sonya Battla, Rizwan Beyg, and Maheen Khan - showed a variety of casual and formal outfits as well as western wear, jackets, and accessories.

http://www.riazhaq.com/2010/12/pakistans-year-2010-other-story.html

Apr 16, 2013

Riaz Haq

Here's a WSJ interview of Mira Nair about The Reluctant Fundamentalist, the movie:

What led you, an Indian artist, to make this film about Pakistan?

Without my knowing it, this world had nourished me culturally. My father grew up in pre-partition Lahore, so I was raised Lahori in India, speaking Urdu, knowing Faiz's poetry, listening to Iqbal Bano's songs. As a child of modern India, I'd made a moving journey to Pakistan in 2004, when I was invited to speak because my films are popular there. We were treated like rock stars. The warmth, the refinement, the expression of the arts—music, painting—was dazzling. I'd stepped into a familiar culture and was inspired to make a tale of contemporary Pakistan. Six months later, Mohsin's book gave me the opportunity to show a Pakistan you never see in newspapers. Its dialogue with America was appealing because we don't see issues from two sides; it's always a monologue, never a conversation.

The novel is structured as a recollective monologue. You've added characters and changed the end. Was that for cinema purposes?

We haven't altered the spirit of the novel. The film is indebted to the tightrope that the protagonist walks in the novel. We don't know who Changez is. That propelled the screenwriting: What kind of fundamentalist is he? I wanted the Pakistani family to be real human characters. I changed the brother into a sister because "Muslim" movies are about men, but in Pakistan women are the heartbeat of every gathering. They're bawdy, strong, opinionated, beautiful. So I wanted a female—and made her a Bond-chick in Pakistan TV's longest-running comedy. We added a third act: In the novel, Changez returns to Pakistan. I wanted to know what he'd be doing there such that an American wants to talk to him. That makes the film timely, not dated. The world's changed: Osama was killed—before our eyes—and the CIA's Raymond Davis went shooting in Pakistani streets. These were uncanny happenings.

There are three screenwriters credited. Why so many?

I wanted a dialogue, an unpredictable meeting of equals, between Changez and Bobby, the American. Calling Hollywood A-listers, I was amazed by their ignorance [of Pakistan] and arrogance, so I picked Mohsin and Ami Boghani to write the first draft. We three did the second draft, about Pakistani life, in Lahore. Then I found Bill Wheeler to tie the skeins together. The four of us huddled together and mapped it out collaboratively before Bill rewrote it. Bill was humble about what he didn't know and very good at what he knew.

Were there logistical problems in filming in three continents?

That's the beauty of production. We shot "Istanbul" in one 18-hour day in an old Delhi orphanage. Only the exteriors were shot in Turkey. The Lahore scenes were shot over 20 days in Old Delhi—the tea house built in a 16th-century structure—with four days in Lahore's streets. New York interiors were shot in Atlanta, which gives a 40% tax rebate, with only four days in New York. We hired 150 Filipinos, put them in hard hats and made a Philippine factory in hi-tech Noida, outside Delhi. I didn't want to sacrifice the globalization—the film's about the divided self in this era: Who are you? Where are you from? Where are you going? Where will you matter? These are the questions today. I didn't want to reduce that scope. I worked with my old team, hired local crews, shot digitally. Knowing how to cut costs comes with experience.

The film contrasts Wall Street's corporate culture with the old-world refinement of middle-class Pakistanis......

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323735604578436902785...

Apr 21, 2013

Riaz Haq

Here's a PakistanToday story on Pakistan Academy of Letters:

The Pakistan Academy of Letters (PAL) has published translation of several literary works in English and other international languages to promote Urdu and other regional languages.

The 340 pages text includes translation of literary writings in Urdu, Punjabi, Potohari, Sindhi, Pashto, Balochi, Brahvi, and Khowari. The publication also includes work of Pakistani writers in English. Noon Meem Rashid’s poem “Hasan Kooza Gar” is translated into English, Arabic, French, Turkish, and Chinese.

The publication was unveiled by PAL Chairman Abdul Hameed in an event held at PAL’s Writer’s House.

This anthology represents various genres including prose, poetry, article, column and poetry. The publication is divided into sections based on the languages. The separators are designed by renowned artist Jamal Shah while the book jacket is designed by another art giant Dr Ajaz Anwar.

While talking to the Pakistan Today, PAL Director General Zaheer-ud-Din Malik said, “It is one of PAL’s main responsibilities to translate Pakistani literature into international languages.” We want to hand out this publication to ambassadors and foreign missions for helping them explore the real face of Pakistani society, he added. Malik said the only 500 copies of the publication were printed due to lack of resources but it would help us promote our mission.

PAL has also been unable to complete the Faiz Ahmed Faiz Auditorium due to lack of funds. The auditorium was due to be inaugurated on Faiz’s 100th birthday in February 2011.

http://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2013/04/24/city/islamabad/pal-publi...

Apr 24, 2013

Riaz Haq

Here's Mira Nair talking with Bollywood Life:

...Based on the novel of the same name by Pakistani writer Mohsin Hamid, the film tells the story of two conflicting ideologies – the “fundamentalism” of the capitalists and that of the terrorists – through a young Pakistani man chasing his American dream.

“The film not only gave me the opportunity to make that modern tale on Pakistan, but it was also in its bones a dialogue with America,” said Nair in a phone interview from New York. “There is so little of conversation between this part of the world and that part of the world and especially post 9/11 that conversation has become a monologue,” she said. She saw in The Reluctant Fundamentalist a “chance to create a bridge, create a dialogue,” she said.

Nair said she has tried “to make a film that questions who is the other or who do we make to feel like the other and make something that’s not reductionist”, where one is either a good guy or a bad guy and things are black or white. In a complicated world “we are many things. Not just one thing – not just Indian or American or just this or that, but we are a combination of so many identities especially in this globalising world,” she said.

And that’s what the film tries to approximate through the characters of protagonist Changez Khan (Riz Ahmed) and Bobby (Liev Schreiber), an American journalist, whom he tells about his experiences in the US at a teahouse in Lahore, “and the worlds they live in”.

“I think our film is about the mutual suspicions that these two worlds have for each other,” Nair said. “And in understanding why this suspicion exists, as we try to explain or reveal in our film. That could be illuminating in terms of understanding how such a shift can happen in an individual…to bring men to an act of terror this way as we see in Boston,” Nair said.

“I have to be optimistic,” she said, but her film was just “an early step because we are still paying the price of reaction, that quick reach of reactions that I have seen happen in the country post 9/11.”

Delhi, which is a twin city to Lahore, doubled for the Pakistani city for filming the teahouse, the university and all the interiors. A second unit filmed the streets of Lahore and the exteriors for four days without the actors. “No, we didn’t have that terror problem even creating Lahore in Delhi,” the director said.

“The first bolt of inspiration” that Nair had to make a film on Pakistan was in 2004 when she first visited Lahore, where her father had studied, and was “dazzled by the kind of largesse of warmth and spirit and love” she received. “The creative sparks that I saw there – the music, the paintings – in every way it was full of an artistic expression that I certainly never associated with or knew about with what we read about Pakistan in newspapers,” Nair said.

Reading Mohsin’s “wonderful novel” in manuscript form 18 months later, she realised that like the writer “I have lived half my life in New York City and half my life in the sub-continent and I knew both worlds within and somewhat without.”

When Nair finally set out to make The Reluctant Fundamentalist, Mohsin joked if she was making Monsoon Terrorist “because I love music, I love naach, gaana, tamasha,” said the maker of films like Monsoon Wedding, Mississippi Masala and The Namesake.

In fact, “Music is a huge part of my breathing universe and the modern music in Pakistan is just unbelievably inspiring” in its rendition of old traditional sources like the qawwali and the ghazal, she said.

And the poems of the sub-continent’s revolutionary poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz “were a huge cornerstone of why I made the film in the first place,” said Nair who has used three of his poems - Bol, ki lab azaad hain tere, Mori arz suno and Dil jalane ki baat....

http://www.bollywoodlife.com/news-gossip/the-reluctant-fundamentali...

Apr 28, 2013

Riaz Haq

Here's a Daily Times report on Islamabad Literature Festival:

..The ILF, organised by the Oxford University Press, opened on Tuesday. The two-day festival with 70 speakers and more than 35 sessions/events is being held at a local hotel. Approximately 6,000 participants visited the festival on the first day. Oxford University Press Managing Director Ameena Saiyid welcomed the guests. In her speech, she observed that a common system or syllabus was not the solution, as teachers’ training, improving curriculum and providing children with better quality books would encourage the reading habit.

ILF co-founder Asif Farrukhi said that literature remains the medium to express society’s feelings and status. Quoting writer Intizar Husain, he said, “This is the time of signs.” Intizar Husain said that the last century started by promising a bright future, but it turned into a century of two world wars, fascism and now intolerance too had spread to Asia.

Kamila Shamsie, winner of Granta magazine’s Best of Young Writers’ Award for her contribution as a novelist, paid tribute to Intizar Husain and his novel ‘Basti’. “In Pakistan, it is taught that history is confluence of religion. Actually, history is confluence of geography. We deny our thousands of years of historical background,” she lamented.

In another thought-provoking session on his book ‘Pakistan on the brink’ Ahmed Rashid said that he still felt that Pakistan could be salvaged “if our foreign and national security policies are changed diametrically”.

“We have to stop thinking that we have the right to decide the faith of Afghanistan and stop relying on jihadi groups to achieve the foreign policy objectives. We have failed to take advantage of our geo-political position to build our economy. We need ceasefire in Afghanistan to help bring peace to Pakistan,” he observed.

The session was moderated by Daily Times Editor Rashid Rehman, who raised incisive questions. In the session titled ‘Pakistani English Poetry is Alive and Well: New Directions, New Voices’, Ilona Yusuf, Athar Tahir, Harris Khalique and Muneeza Shamsie were of the view that English poetry was being written in Pakistan and had considerable audience. There was consensus among the participants that there should be some publication or means of promotion of Pakistani English poetry.

In other sessions, Abdullah Hussain and Ahmed Shah captivated the audience in their readings and conversations; Amjad Shahzad, Zubair Hasrat, Arif Tabassum and Muhib Wazir discussed ‘New Voices in Pushto Poetry’ with Raj Wali Khattak and Ahmad Fouad; in ‘Shah Hussain and Sufi Classical Poetry in Punjabi’, Harris Khalique had an interesting discussion with Sarwat Mohiuddin; on the sensitive issue of ‘Politics of Child Labour’, Samar Minallah Khan, Anees Jillani, Taimur Rahman with Baela Jamil raised important issues regarding child labour and under-aged servants; and Muneeza Shamsie with Ahmed Rashid elaborated on ‘Pakistani English Novels in the New Millennium’.

In the session on ‘Dynastic politics’, to question by the Moderator Babar Ayaz that why political dynasties are scorned by middle classes, while dynasties in other professions like lawyers, writers and doctors are approved, eminent historian Hamida Khuro said that political dynasties were disliked because in democracy people like to have meritocracy and politicians have power to affect the lives of the people....

http://www.dailytimes.com.pk/default.asp?page=2013\05\01\story_1-5-2013_pg11_1

Apr 30, 2013

Riaz Haq

Here's a brief bio of Intizar Husain, the first Pakistani Urdu writer whose book has been short-listed for the UK's Man Booker prize:

Intizar Husain was born in India before partition in Uttar Pradesh, on December 21st 1925. He emigrated to Pakistan in 1947 and lives in Lahore.

He gained a master’s degree in Urdu and another in English literature. The author of short stories and novels, he worked for the Urdu daily, Imroze. He worked for the Urdu daily Mashriq for many years and now writes a weekly column for the Karachi-based English language newspaper, Dawn.

A chronicler of change, Husain has written five novels and published seven collections of short stories. Only one of his novels is translated into English and there are five volumes of his short stories published in English translations.

Naya Gar (The New House) paints a picture of Pakistan during the ten-year dictatorship of General Zia-ul-Haq. Agay Sumandar Hai (Beyond is the Sea) contrasts the spiralling urban violence of contemporary Karachi with a vision of the lost Islamic realm of al-Andalus, in modern Spain.

Basti, his 1979 novel, which traces the psychic history of Pakistan through the life of one man, Zakir, has just been republished as one of the New York Review of Books Classics. Keki Daruwalla, writing in The Hindu in 2003, said “Intizar Husain’s stories often tread that twilight zone between fable and parable. And the narrative is spun on an oriental loom.

http://www.themanbookerprize.com/people/intizar-husain

May 18, 2013