PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

India in Crisis: Unemployment and Hunger Persist After Waves of COVID

India lost 6.8 million salaried jobs and 3.5 million entrepreneurs in November alone. Many among the unemployed can no longer afford to buy food, causing a significant spike in hunger. The country's economy is finding it hard to recover from COVID waves and lockdowns, according to data from multiple sources. At the same time, the Indian government has reported an 8.4% jump in economic growth in the July-to-September period compared with a contraction of 7.4% for the same period a year earlier. This raises the following questions: Has India had jobless growth? Or its GDP figures are fudged? If the Indian economy fails to deliver for the common man, will Prime Minister Narendra Modi step up his anti-Pakistan and anti-Muslim rhetoric to maintain his popularity among Hindus?

|

| Labor Participation Rate in India. Source: CMIE |

Unemployment Crisis:

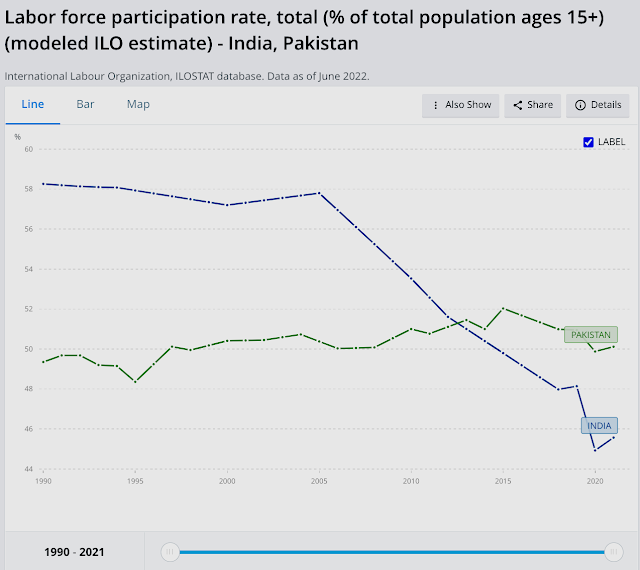

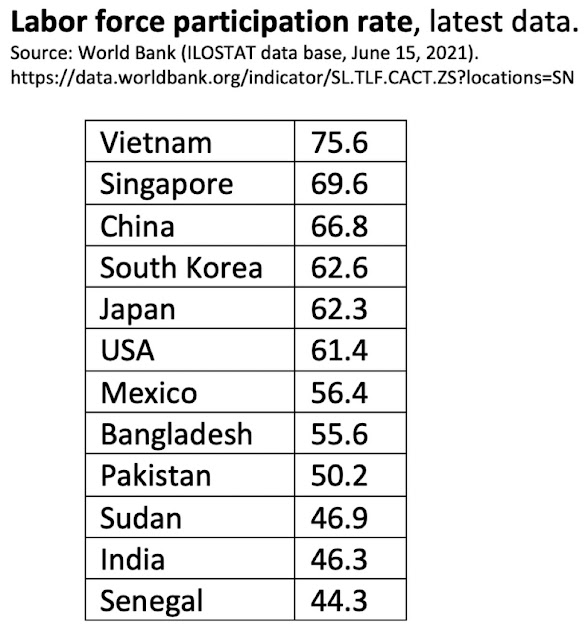

India lost 6.8 million salaried jobs and its labor participation rate (LPR) slipped from 40.41% to 40.15% in November, 2021, according to the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). In addition to the loss of salaried jobs, the number of entrepreneurs in India declined by 3.5 million. India's labor participation rate of 40.15% is lower than Pakistan's 48%. Here's an except of the latest CMIE report:

"India’s LPR is much lower than global levels. According to the World Bank, the modelled ILO estimate for the world in 2020 was 58.6 per cent (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.ZS). The same model places India’s LPR at 46 per cent. India is a large country and its low LPR drags down the world LPR as well. Implicitly, most other countries have a much higher LPR than the world average. According to the World Bank’s modelled ILO estimates, there are only 17 countries worse than India on LPR. Most of these are middle-eastern countries. These are countries such as Jordan, Yemen, Algeria, Iraq, Iran, Egypt, Syria, Senegal and Lebanon. Some of these countries are oil-rich and others are unfortunately mired in civil strife. India neither has the privileges of oil-rich countries nor the civil disturbances that could keep the LPR low. Yet, it suffers an LPR that is as low as seen in these countries".

|

| Labor Participation Rates in India and Pakistan. Source: World Bank... |

|

| Labor Participation Rates for Selected Nations. Source: World Bank/ILO |

Youth unemployment for ages15-24 in India is 24.9%, the highest in South Asia region. It is 14.8% in Bangladesh 14.8% and 9.2% in Pakistan, according to the International Labor Organization and the World Bank.

|

| Youth Unemployment in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. Source: ILO, WB |

In spite of the headline GDP growth figures highlighted by the Indian and world media, the fact is that it has been jobless growth. The labor participation rate (LPR) in India has been falling for more than a decade. The LPR in India has been below Pakistan's for several years, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO).

|

| Indian GDP Sectoral Contribution Trend. Source: Ashoka Mody |

|

| Indian Employment Trends By Sector. Source: CMIE Via Business Standard |

|

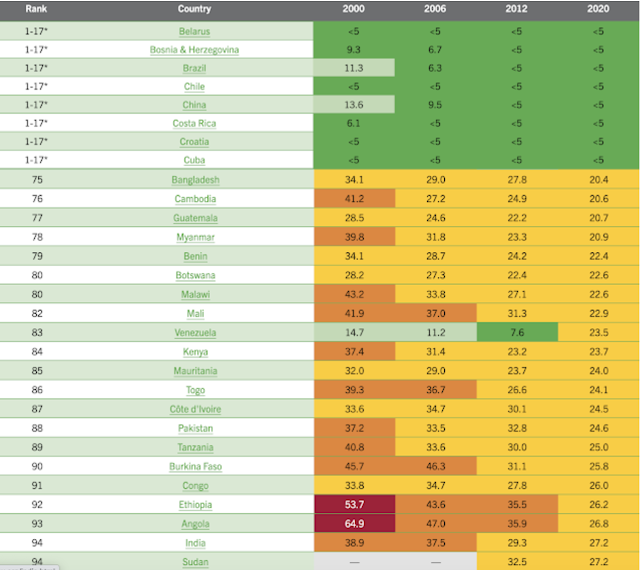

| World Hunger Rankings 2020. Source: World Hunger Index Report |

Hunger and malnutrition are worsening in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia because of the coronavirus pandemic, especially in low-income communities or those already stricken by continued conflict.

India has performed particularly poorly because of one of the world's strictest lockdowns imposed by Prime Minister Modi to contain the spread of the virus.

Hanke Annual Misery Index:

Pakistan's Real GDP:

Vehicles and home appliance ownership data analyzed by Dr. Jawaid Abdul Ghani of Karachi School of Business Leadership suggests that the officially reported GDP significantly understates Pakistan's actual GDP. Indeed, many economists believe that Pakistan’s economy is at least double the size that is officially reported in the government's Economic Surveys. The GDP has not been rebased in more than a decade. It was last rebased in 2005-6 while India’s was rebased in 2011 and Bangladesh’s in 2013. Just rebasing the Pakistani economy will result in at least 50% increase in official GDP. A research paper by economists Ali Kemal and Ahmad Waqar Qasim of PIDE (Pakistan Institute of Development Economics) estimated in 2012 that the Pakistani economy’s size then was around $400 billion. All they did was look at the consumption data to reach their conclusion. They used the data reported in regular PSLM (Pakistan Social and Living Standard Measurements) surveys on actual living standards. They found that a huge chunk of the country's economy is undocumented.

Pakistan's service sector which contributes more than 50% of the country's GDP is mostly cash-based and least documented. There is a lot of currency in circulation. According to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), the currency in circulation has increased to Rs. 7.4 trillion by the end of the financial year 2020-21, up from Rs 6.7 trillion in the last financial year, a double-digit growth of 10.4% year-on-year. Currency in circulation (CIC), as percent of M2 money supply and currency-to-deposit ratio, has been increasing over the last few years. The CIC/M2 ratio is now close to 30%. The average CIC/M2 ratio in FY18-21 was measured at 28%, up from 22% in FY10-15. This 1.2 trillion rupee increase could have generated undocumented GDP of Rs 3.1 trillion at the historic velocity of 2.6, according to a report in The Business Recorder. In comparison to Bangladesh (CIC/M2 at 13%), Pakistan’s cash economy is double the size. Even a casual observer can see that the living standards in Pakistan are higher than those in Bangladesh and India.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

Indian Economy Grew Just 0.2% Annually in Last Two Years

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

Pakistan's 2012 GDP Estimated at $401 Billion

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid1...

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Cou...

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan Fares Marginally Better Than India On Disease Burdens

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

COVID Lockdown Decimates India's Middle Class

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

How Has India Built Large Forex Reserves Despite Perennial Trade De...

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on January 27, 2023 at 9:11pm

-

Two-wheeler volumes drop to FY 10/12 levels. Huge drop in entry level Motorcycle sales indicate pain in rural/semi-urban areas. Experts say at least 50% capacity lying idle at two-wheeler factories.

Point to deeply worrying economic realities.

#India 2-Wheeler Sales Volume Declines to 2012 Level: 12.2 Million in 2022. Capacity utilization down to 50%. #Modi #MakeInIndia #Manufacturing #Unempolyment #economy https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/auto/bikes/two-wheeler-market-s...

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/auto/bikes/two-wheeler-market-s...

https://twitter.com/haqsmusings/status/1619198354780733441?s=20&...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on February 14, 2023 at 10:13pm

-

#India, soon world's most populous nation, doesn't know how many people it has. Critics of PM #Modi have accused his gov’t of delaying the census to hide data on politically sensitive issues, such as #unemployment, ahead of national #elections due in 2024.

https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-soon-worlds-most-populous...

Experts say the delay in updating data like employment, housing, literacy levels, migration patterns and infant mortality, which are captured by the census, affects social and economic planning and policy making in the huge Asian economy.

Calling census data "indispensable", Rachna Sharma, a fellow at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, said studies like the consumption expenditure survey and the periodic labour force survey are estimations based on information from the census.

"In the absence of latest census data, the estimations are based on data that is one decade old and is likely to provide estimates that are far from reality," Sharma said.

A senior official at the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation said census data from 2011, when the count was last conducted, was being used for projections and estimates required to assess government spending.

A spokesman for the ministry said its role was limited to providing the best possible projections and could not comment on the census process. The Prime Minister's Office did not respond to requests for comment

Two other government officials, one from the federal home (interior) ministry and another from the office of the Registrar General of India, said the delay was largely due to the government's decision to fine-tune the census process and make it foolproof with the help of technology.

The home ministry official said the software that will be used to gather census data on a mobile phone app has to be synchronised with existing identity databases, including the national identity card, called Aadhaar, which was taking time.

The office of the Registrar General of India, which is responsible for the census, did not respond to a request for comment.

The main opposition Congress party and critics of Prime Minister Narendra Modi have accused the government of delaying the census to hide data on politically sensitive issues, such as unemployment, ahead of national elections due in 2024.

"This government has often displayed its open rivalry with data," said Congress spokesperson Pawan Khera. "On important matters like employment, Covid deaths etc., we have seen how the Modi government has preferred to cloak critical data.”

The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party's national spokesperson, Gopal Krishna Agarwal, dismissed the criticism.

"I want to know on what basis they are saying this. Which is the social parameter on which our performance in nine years is worse than their 65 years?" he said, referring to the Congress party's years in power.

TEACHERS' TRAVAILS

The United Nations has projected India's population could touch 1,425,775,850 on April 14, overtaking China on that day.

The 2011 census had put India's population at 1.21 billion, meaning the country has added 210 million, or almost the number of people in Brazil, to its population in 12 years.

India's census is conducted by about 330,000 government school teachers who first go door-to-door listing all houses across the country and then return to them with a second list of questions.

They ask more than two dozen questions each time in 16 languages in the two phases that will be spread over 11 months, according to the plan made for 2021.

The numbers will be tabulated and final data made public months later. The entire exercise was estimated to cost 87.5 billion rupees ($1.05 billion) in 2019.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on February 19, 2023 at 7:12pm

-

India’s economic activity cooled off at the start of the year as higher borrowing costs tempered demand at home and abroad, signaling more pain ahead as the global economy slows down.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-02-19/india-s-economic...

The needle on a dial measuring so-called animal spirits moved left and was back where it was for six straight months before showing momentum in December. Falling exports and a slack in manufacturing and services drove the weakness in business activity, offsetting improvement in consumption drivers reflected by tax collections and job growth, according to eight high-frequency indicators tracked by Bloomberg.

Domestic recovery, that has been driving momentum so far, is getting wobbly. The Reserve Bank of India, which has raised borrowing costs six times since May to 6.50 per cent, is seen increasing interest rates again in its April review amid inflation topping estimates and further tightening by global central banks.

Bloomberg’s animal spirits barometer uses a three-month weighted average to smooth out volatility in single-month readings:

Business Activity

Purchasing managers’ surveys indicated activity in both manufacturing and services slacked in January. Output and new orders grew at softer paces, and dragged the composite index lower from an 11-year high in December.

“Although manufacturers received new orders from international markets, the increase was slight at best and moderated considerably to a ten-month low,” said Pollyanna De Lima, economics associate director at S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Exports

Exports fell 6.58 per cent in January from a year ago to US$32.9 billion (S$43.9 billion), data released by the Trade Ministry showed, indicating lower demand for goods abroad. Imports dropped 3.63 per cent from a year earlier and that pushed the trade gap to the lowest in a year, fueling hopes of a significantly narrower current account deficit.

The sharp fall in imports reflects the moderation in discretionary demand in the goods sector and the decline in commodity prices, said Garima Kapoor, economist at Elara Capital.

Consumer Activity

Liquidity in the banking system tightened, but credit growth picked up again, rising 16.33% in January, from 14.87 per cent in December, Reserve Bank of India data show.

Goods and services tax collections, which help measure consumption in the economy, rose 10.5 per cent from a year earlier to 1.56 trillion rupees – a feat achieved only once before in the history of the levy introduced in 2017. New vehicle registrations surged 14 per cent in the month, with passenger vehicle sales growing 22 per cent year-on-year, according to data from the Federation of Automobile Dealers Associations.

Market Sentiment

Electricity consumption, a widely used proxy to gauge demand in the industrial and manufacturing sectors, held steady, with the peak requirement last month rising to 173 gigawatt from 171 gigawatt in December due to increased heating requirements. India’s unemployment rate dropped to 7.14 per cent, from a 16-month high of 8.30 per cent a month ago, according to data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy. BLOOMBERG

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 3, 2023 at 7:35am

-

Is India’s boom helping the poor?

What vehicle sales reveal about the country’s growth

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/03/02/is-india...

In a land where labour is cheap, the man who drives the most luxury cars is not a billionaire. He is a parking attendant. On a meagre salary, he must park, double-park and triple-park cars in tight spaces, and then extricate them. In India, where car sales have increased by 16% since the start of the covid-19 pandemic—a trend partly driven by the growing popularity of hefty sports-utility vehicles—this tricky job is becoming even more difficult.

To many, India’s automobile boom symbolises the country’s superfast economic rise. On February 28th new figures revealed that India’s gdp grew by 4.4% year on year in the last quarter of 2022, down from 6.3% in the previous quarter. Despite the slowdown, the imf expects India to be the fastest-growing major economy in 2023, and to account for 15% of global growth. The governing Bharatiya Janata Party (bjp) believes the country is in the midst of Amrit Kaal, an auspicious period that will bring prosperity to all Indians.

Not everyone is convinced by the bjp’s boosterism. To sceptics, rising vehicle sales in fact demonstrate the unsavoury lopsidedness of India’s economic growth. Indeed, purchases of two-wheelers, such as scooters and motorcycles, have sputtered since covid hit, and are down by 15% since 2019. These are the vehicles of the masses: half of households own a two-wheeler; fewer than one in ten own a car.

Not many questions are more central to Indian politics than the wellbeing of the country’s everyman. The problem is that answering the question is fraught with difficulty. Official statistics are patchy. Ministers have not published a poverty estimate in more than a decade. Thus assessments and inferences must be made using other surveys and data sets, such as vehicle sales.

These suggest poverty reduction has stalled, and maybe even reversed. According to a survey of 44,000 households by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (cmie), a research outfit, only 6% of India’s poorest households—those bringing in less than 100,000 rupees ($1,200) a year—believe their families are better off than a year ago. The recovery from the pandemic, when harsh lockdowns whacked the economy, has been horribly slow.

The World Bank estimates shutdowns pushed 56m Indians into extreme poverty. Since then inflation has further eroded purchasing power: real wages in rural areas, where most of the poor live, have stagnated, and annual inflation jumped to 6.5% in January. Poor families, for whom food makes up 60% of household expenditure, have felt the strongest pinch. Rural food costs have risen by 28% since 2019; onion prices by an eye-watering 51%.

Labour-market data also bely India’s impressive headline growth figures. Take-up for a rural-employment programme, which guarantees low-wage work to participants, remains above pre-covid levels. cmie surveys suggest the unemployment rate is also higher, averaging more than 7% over the past two years. Many people have given up looking: labour-force participation rates have fallen since the pandemic.

There are plenty of problems with India’s economy, from poor primary education to an inability to grow its limited manufacturing sector. But these were present even as previous growth spurts lifted millions out of poverty. Recent pains are thus more likely to reflect the pandemic’s after-effects. Construction firms in cities, for example, complain of labour shortages, as many workers who headed to villages during lockdowns have not yet returned.

These may at last be starting to ease. The latest data releases suggest that rural wages may be picking up. Deposits in bank accounts set up for the poor are also rising. Even sales of two-wheelers are slowly creeping up. A lot more improvement will be needed, however, for claims of Amrit Kaal to ring true.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 4, 2023 at 8:21pm

-

"India is Broken" writes Princeton Economist Ashoka Modi. Says #Indians, mostly illiterate and poor, hunger for freedom and prosperity but their politicians from #Nehru to #Modi have “betrayed the economic aspirations” of millions. #BJP https://www.wsj.com/articles/india-is-broken-review-the-difficult-f... via @WSJBooks

Ashoka Mody, who was for many years a senior economist at the International Monetary Fund, is the sort of quietly efficient global technocrat who retires to a professorship at a prestigious school—in his case, Princeton. Yet he’s different from his faceless ilk of briefcase-bearers in one astonishing way: 13 years ago, an attempt was made on his life. The alleged assailant, thought to have been passed over for a job at the IMF by Mr. Mody, shot him in the jaw outside his house in Maryland.

He recovered with remarkable verve, his intellectual drive intact. Yet a mood of gloom and pessimism is unmistakable in “India Is Broken.” Today, 75 years after independence from Britain, Mr. Mody believes that India’s democracy and economy are in a state of profound malfunction. The book’s tale, he writes, “is one of continuous erosion of social norms and decay of political accountability.” You might add that it is also a tale of an audacious political experiment on the brink of failure.

India started its post-independence journey, says Mr. Mody, as “an improbable democracy” whose citizens, mostly illiterate and poor, hungered for freedom and prosperity. Generations of Indian politicians—from Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister, to Narendra Modi, the present one—have “betrayed the economic aspirations” of millions. India’s democracy no longer protects fundamental rights and freedoms in a nation over which “a blanket of violence” has fallen. A belief in “equality, tolerance and shared progress” has disappeared. And the country’s collapse isn’t just political and economic; it’s also moral and spiritual.

------------

A notable weakness in Mr. Mody’s analysis is his denial that the economic policies of Nehru and his successors were socialist. He writes of Nehru’s “alleged socialist legacy” and adds that it is a “mistake to identify central planning or big government as socialism.” Socialism, he insists, “means the creation of equal opportunity for all,” which India’s policy makers weren’t doing. Ergo, India wasn’t socialist.

If these protestations are almost laughable, Mr. Mody’s solution also invites some derision. Hope for India, he says, lies in making it a “true democracy.” And how can that be done? “We must move to an equilibrium in which everyone expects others to be honest.” This “honest equilibrium,” he says, will promote enough trust for Indians to work together “in the long-haul tasks of creating public goods and advancing sustainable development” and awakening “civic consciousness.” Mr. Mody, it is clear, has a dream. It is naïve, and it is corny. India, alas, will continue to be “broken” for many years to come.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 5, 2023 at 9:51pm

-

Ex Central Bank Chief Raghu Rajan: 'India dangerously close to Hindu rate of growth'. #Hindu rate of growth is a term describing low #Indian economic growth rates from the 1950s to the 1980s, which averaged around 4%. #Modi #BJP #economy #Hindutva

https://www.deccanherald.com/business/economy-business/india-danger...

Sounding a note of caution, former Reserve Bank Governor Raghuram Rajan has said that India is "dangerously close" to the Hindu rate of growth in view of subdued private sector investment, high interest rates and slowing global growth.

Rajan said that sequential slowdown in the quarterly growth, as revealed by the latest estimate of national income released by the National Statistical Office (NSO) last month, was worrying. Hindu rate of growth is a term describing low Indian economic growth rates from the 1950s to the 1980s, which averaged around 4 per cent. The term was coined by Raj Krishna, an Indian economist, in 1978 to describe the slow growth.

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the third quarter (October-December) of the current fiscal slowed to 4.4 per cent from 6.3 per cent in the second quarter (July-September) and 13.2 per cent in the first quarter (April-June).

The growth in the third quarter of the previous financial year was 5.2 per cent. "Of course, the optimists will point to the upward revisions in past GDP numbers, but I am worried about the sequential slowdown. With the private sector unwilling to invest, the RBI still hiking rates, and global growth likely to slow later in the year, I am not sure where we find additional growth momentum," Rajan said in an email interview to PTI.

Recently, Chief Economic Advisor V Anantha Nageswaran had attributed the subdued quarterly growth to the upward revision of estimates of national income for the past years. The key question is what Indian growth will be in fiscal 2023-24, Rajan said, adding "I am worried that earlier we would be lucky if we hit 5 per cent growth. The latest October-December Indian GDP numbers (4.4 per cent on year ago and 1 per cent relative to the previous quarter) suggest slowing growth from the heady numbers in the first half of the year. "My fears were not misplaced. The RBI projects an even lower 4.2 per cent for the last quarter of this fiscal. At this point, the average annual growth of the October-December quarter relative to the to the similar pre-pandemic quarter 3 years ago is 3.7 per cent. "This is dangerously close to our old Hindu rate of growth! We must do better." The government, he said, was doing its bit on infrastructure investment but its manufacturing thrust is yet to pay dividends. The bright spot is services, he said, adding "it seems less central to government efforts." On a query regarding the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme, Rajan said any scheme in which the government pours money will create jobs and any scheme which elevates tariffs on output while offering bonuses for final units produced in India will create production in India, and exports. "A sensible evaluation would ask how many jobs are being created and at what price per job. By the government's own statistics, 15 per cent of the proposed investment has come in but only 3 per cent of the predicted jobs have been created. This does not sound like success, at least not yet," Rajan said.

Furthermore, even if the scheme fully meets the government's expectations over the next few years, it will create only 0.6 crore jobs, a small dent in the jobs India needs over the same period, the former RBI Governor said. "Similarly, government spokespersons point to the rise in cell phone exports as evidence that the scheme is working. But if we are subsidising every cell phone that is exported, this is an obvious outcome.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 5, 2023 at 9:51pm

-

Ex Central Bank Chief Raghu Rajan: 'India dangerously close to Hindu rate of growth'. #Hindu rate of growth is a term describing low #Indian economic growth rates from the 1950s to the 1980s, which averaged around 4%. #Modi #BJP #economy #Hindutva

https://www.deccanherald.com/business/economy-business/india-danger...

Furthermore, even if the scheme fully meets the government's expectations over the next few years, it will create only 0.6 crore jobs, a small dent in the jobs India needs over the same period, the former RBI Governor said. "Similarly, government spokespersons point to the rise in cell phone exports as evidence that the scheme is working. But if we are subsidising every cell phone that is exported, this is an obvious outcome.

The key question is how much value added is done in India. It turns (out to be) very little so far," he said. Rajan said cell phone parts imports have also gone up, so net exports in the cell phone sector, the relevant measure that no one in government talks about, is pretty much where it was when the scheme started. "Except, we have also spent money on subsidies. Foxconn just announced a big factory to produce parts but they have been saying they will invest for a long time. I think we need a lot more evidence before celebrating the success of the PLI scheme," he said.

Currently, Rajan is the Katherine Dusak Miller Distinguished Service Professor of Finance at The University of Chicago Booth School of Business. He further said the most developed economies of the world are largely service economies, so you can be a large economy without a large presence in manufacturing.

"Services do not just account for the majority of our unicorns, services can also provide a lot of semi-skilled jobs in construction, transport, tourism, retail, and hospitality. So let us not deride service jobs – indeed while the fraction of manufacturing jobs has stagnated in India, services have absorbed the exodus from agriculture." "We need to work on both manufacturing and services to create the jobs we need, and fortunately, many of the inputs both (services and manufacturing) need schooling, skilling...," he said.

On what measures the government should take to improve oversight of private family companies to address worries after the Hindenburg allegations on Adani Group, Rajan said: "I don't think the issue is of more oversight over private companies". The issue is of reducing non-transparent links between government and business, and of letting, indeed encouraging, regulators do their job, he said. "Why has SEBI not yet got to the bottom of the ownership of those Mauritius funds which have been holding and trading Adani stock? Does it need help from the investigative agencies?," Rajan wondered.

Adani group has been under severe pressure since the US short-seller Hindenburg Research on January 24, accused it of accounting fraud and stock manipulation, allegations that the conglomerate has denied as "malicious", "baseless" and a "calculated attack on India".

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 21, 2023 at 1:38pm

-

Both Russia and Ukraine reported higher levels of happiness in the latest report despite the escalation of the conflict between the two countries since February 2022. According to the index, Russia’s ranking improved from 80 in 2022 to 70 this year, while Ukraine’s ranking improved from 98 to 92. The 2022 report was based on data from 2019 to 2021.

John Helliwell, one of the authors of the World Happiness Report, said that benevolence, especially acts of kindness towards strangers, increased dramatically in 2021 and remained high in 2022, CNN reported.

“Even during these difficult years, positive emotions have remained twice as prevalent as negative ones, and feelings of positive social support twice as strong as those of loneliness,” he said.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 30, 2023 at 4:59pm

-

Hype over #India’s #economic boom is dangerous myth masking real problems. It’s built on a disingenuous numbers game.

No silver bullet that will fix weak job creation, a small, uncompetitive #manufacturing sector & gov’t schemes fattening corporate profits

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3215379/hype-over-indi...

by Ashoka Mody

Indian elites are giddy about their country’s economic prospects, and that optimism is mirrored abroad. The International Monetary Fund forecasts that India’s GDP will increase by 6.1 per cent this year and 6.8 per cent next year, making it one of the world’s fastest-growing economies.

Other international commentators have offered even more effusive forecasts, declaring the arrival of an Indian decade or even an Indian century.

In fact, India is barrelling down a perilous path. All the cheerleading is based on a disingenuous numbers game. More so than other economies, India’s yo-yoed in the three calendar years from 2020 to 2022, falling sharply twice with the emergence of Covid-19 and then bouncing back to pre-pandemic levels. Its annualised growth rate over these three years was 3.5 per cent, about the same as in the year preceding the pandemic.

Forecasts of higher future growth rates are extrapolating from the latest pandemic rebound. Yet, even with pandemic-related constraints largely in the past, the economy slowed in the second half of 2022, and that weakness has persisted this year. Describing India as a booming economy is wishful thinking clothed in bad economics.

Worse, the hype is masking a problem that has grown in the 75 years since independence: anaemic job creation. In the next decade, India will need hundreds of millions more jobs to employ those who are of working age and seeking work. This challenge is virtually insurmountable considering that the economy failed to add any net new jobs in the past decade, when 7 million to 9 million new jobseekers entered the market each year.

This demographic pressure often boils over, fuelling protests and episodic violence. In 2019, 12.5 million people applied for 35,000 job openings in the Indian railways – one job for every 357 applicants. In January 2022, railway authorities announced they were not ready to make the job offers. The applicants went on a rampage, burning train cars and vandalising railway stations.

With urban jobs scarce, tens of millions of workers returned during the pandemic to eking out meagre livelihoods in agriculture, and many have remained there. India’s already-distressed agriculture sector now employs 45 per cent of the country’s workforce.

Farming families suffer from stubbornly high underemployment, with many members sharing limited work on plots rendered steadily smaller through generational subdivision. The epidemic of farmer suicides persists. To those anxiously seeking support from rural employment-guarantee programmes, the government unconscionably delays wage payments, triggering protests.

For far too many Indians, the economy is broken. The problem lies in the country’s small and uncompetitive manufacturing sector.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 30, 2023 at 5:00pm

-

India is Broken

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3215379/hype-over-indi...

by Ashoka Mody

Since the liberalising reforms of the mid-1980s, the manufacturing sector’s share of GDP has fallen slightly to about 14 per cent, compared to 27 per cent in China and 25 per cent in Vietnam. India commands less than a 2 per cent global share of manufactured exports, and as its economy slowed in the second half of 2022, the manufacturing sector contracted further.

Yet it is through exports of labour-intensive manufactured products that Taiwan, South Korea, China and now Vietnam came to employ vast numbers of their people. India, with its 1.4 billion people, exports about the same value of manufactured goods as Vietnam does with 100 million people.

Those who believe that India stands at the cusp of greatness usually focus on two recent developments. First, Apple contractors have made initial investments to assemble high-end iPhones in India, leading to speculation that a broader move away from China by manufacturers will benefit India despite the country’s considerable quality-control and logistical problems.

while such an outcome is possible, academic analysis and media reports are discouraging. Economist Gordon H. Hanson says Chinese manufacturers will move labour-intensive manufacturing from the country’s expensive coastal hubs to its less-developed interior, where production costs are lower.

Moreover, investors moving out of China have gone mainly to Vietnam and other countries in Southeast Asia, which like China are members of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. India has eschewed membership in this trade bloc because its manufacturers fear they will be unable to compete once other member states gain easier access to the Indian market.

As for US producers pulling away from China, most are “near-shoring” their operations to Mexico and Central America. Altogether, while some investment from this churn could flow to India, the fact remains that inward foreign investment fell year on year in 2022.

The second source of hope is the Indian government’s Production-Linked Incentive Schemes, which were introduced in early 2021 to offer financial rewards for production and jobs in sectors deemed to be of strategic value. Unfortunately, as former Reserve Bank of India governor Raghuram G. Rajan and his co-authors warn, these schemes are likely to end up merely fattening corporate profits like previous sops to manufacturers.

India’s run with start-up unicorns is also fading. The sector’s recent boomrelied on cheap funding and a surge of online purchases by a small number of customers during the pandemic. But most start-ups have dim prospects for achieving profitability in the foreseeable future. Purchases by the small customer base have slowed and funds are drying up.

Looking past the illusion created by India’s rebound from the pandemic, the country’s economic prognosis appears bleak. Rather than indulge in wishful thinking and gimmicky industrial incentives, policymakers should aim to power economic development through investments in human capital and by bringing more women into the workforce.

India’s broken state has repeatedly avoided confronting long-term challenges and now, instead of overcoming fundamental development deficits, officials are seeking silver bullets. Stoking hype about an imminent Indian century will merely perpetuate the deficits, helping neither India nor the rest of the world.

Ashoka Mody, visiting professor of international economic policy at Princeton University, is the author of India is Broken: A People Betrayed, Independence to Today. Copyright: Project Syndicate

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Pakistanis' Insatiable Appetite For Smartphones

Samsung is seeing strong demand for its locally assembled Galaxy S24 smartphones and tablets in Pakistan, according to Bloomberg. The company said it is struggling to meet demand. Pakistan’s mobile phone industry produced 21 million handsets while its smartphone imports surged over 100% in the last fiscal year, according to …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on April 26, 2024 at 7:09pm

Pakistani Student Enrollment in US Universities Hits All Time High

Pakistani student enrollment in America's institutions of higher learning rose 16% last year, outpacing the record 12% growth in the number of international students hosted by the country. This puts Pakistan among eight sources in the top 20 countries with the largest increases in US enrollment. India saw the biggest increase at 35%, followed by Ghana 32%, Bangladesh and…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on April 1, 2024 at 5:00pm

© 2024 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network