PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

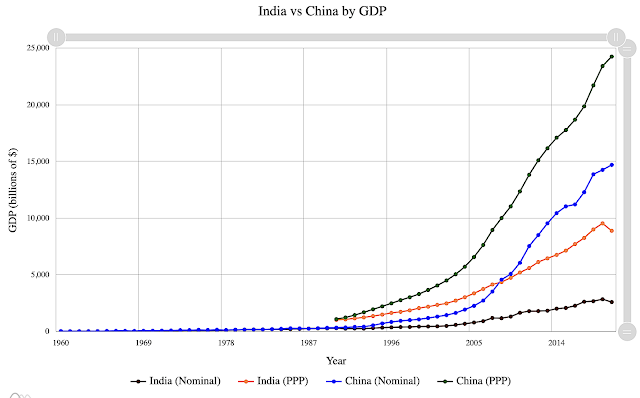

Why Does India Lag So Far Behind China?

Indian mainstream media headlines suggest that Pakistan's current troubles are becoming a cause for celebration and smugness across the border. Hindu Nationalists, in particular, are singing the praises of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and some Pakistani analysts have joined this chorus. This display of triumphalism and effusive praise of India beg the following questions: Why are Indians so obsessed with Pakistan? Why do Indians choose to compare themselves with much smaller Pakistan rather than to their peer China? Why does India lag so far behind China when the two countries are equal in terms of population and number of consumers, the main draw for investors worldwide? Obviously, comparison with China does not reflect well on Hindu Nationalists because it deflates their bubble.

|

| Comparing China and India GDPs. Source: Statistics Times |

|

| Top Patent Filing Nations in 2021. Source: WIPO.Int |

|

| India's Weighting in MSCI EM Index Smaller Than Taiwan's. Source: N... |

The US Commerce Department is actively promoting India Inc to become an alternative to China in the West's global supply chain. US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo recently told Jim Cramer on CNBC’s “Mad Money” that she will visit India in March with a handful of U.S. CEOs to discuss an alliance between the two nations on manufacturing semiconductor chips. “It’s a large population. (A) lot of workers, skilled workers, English speakers, a democratic country, rule of law,” she said.

India's unsettled land border with China will most likely continue to be a source of growing tension that could easily escalate into a broader, more intense war, as New Delhi is seen by Beijing as aligning itself with Washington.

In a recent Op Ed in Global Times, considered a mouthpiece of the Beijing government, Professor Guo Bingyun has warned New Delhi that India "will be the biggest victim" of the US proxy war against China. Below is a quote from it:

"Inducing some countries to become US' proxies has been Washington's tactic to maintain its world hegemony since the end of WWII. It does not care about the gains and losses of these proxies. The Russia-Ukraine conflict is a proxy war instigated by the US. The US ignores Ukraine's ultimate fate, but by doing so, the US can realize the expansion of NATO, further control the EU, erode the strategic advantages of Western European countries in climate politics and safeguard the interests of US energy groups. It is killing four birds with one stone......If another armed conflict between China and India over the border issue breaks out, the US and its allies will be the biggest beneficiaries, while India will be the biggest victim. Since the Cold War, proxies have always been the biggest victims in the end".

Related Links:

Do Indian Aircraft Carriers Pose a Threat to Pakistan's Security?

Can Washington Trust Modi as a Key Ally Against China?

Ukraine Resists Russia Alone: A Tale of West's Broken Promises

Ukraine's Lesson For Pakistan: Never Give Up Nuclear Weapons

AUKUS: An Anglo Alliance Against China?

Russia Sanction: India Profiting From Selling Russian Oil

Indian Diplomat on Pakistan's "Resilience", "Strategic CPEC"

Vast Majority of Indians Believe Nuclear War Against Pakistan is "W...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 20, 2023 at 8:41am

-

In spite of their recent troubles, the Pakistanis (rank 108) are still happier than Indians (rank 126) and Bangladeshis (rank 119), according to the World Happiness Report 2023 released today.

The country rankings show life evaluations (answers to the Cantril ladder question) for each country, averaged over the years 2020-2022.

This is the Cantril ladder: it asks respondents to think of a ladder, with the best possible life for them being a 10 and the worst possible life being a 0. They are then asked to rate their own current lives on that 0 to 10 scale. The rankings are from nationally representative samples for the years 2019-2021.

World Happiness Rankings 2023 based on 3 year average among 137 countries

Finland Rank 1 Score 7.804

China Rank 64 Score 5.818

Pakistan Rank 108 Score 4.555

Bangladesh Rank 119 Score 4.282

India Rank 126 Score 4.036

Lebanon Rank 136 Score 2.392

Afghanistan Rank 137 Score 1.859

Happiness Gap Between Top Half and Bottom Half

Pakistan 4.427

India 4.64

Country name Ladder score Standard error of ladder score upper whisker lower whisker Logged GDP per capita Social support Healthy life expectancy Freedom to make life choices Generosity Perceptions of corruption Ladder score in Dystopia Explained by: Log GDP per capita Explained by: Social support Explained by: Healthy life expectancy Explained by: Freedom to make life choices Explained by: Generosity Explained by: Perceptions of corruption Dystopia + residual

Finland 7.804 0.036 7.875 7.733 10.792 0.969 71.150 0.961 -0.019 0.182 1.778 1.888 1.585 0.535 0.772 0.126 0.535 2.363

China 5.818 0.044 5.905 5.731 9.738 0.836 68.689 0.882 -0.041 0.727 1.778 1.510 1.249 0.468 0.666 0.115 0.145 1.666

5.818 0.044 5.905 5.731 9.738 0.836 68.689 0.882 -0.041 0.727 1.778 1.510 1.249 0.468 0.666 0.115 0.145 1.666Pakistan 4.555 0.077 4.707 4.404 8.540 0.601 57.313 0.766 0.008 0.787 1.778 1.081 0.657 0.158 0.511 0.141 0.102 1.907

Bangladesh 4.282 0.068 4.416 4.148 8.685 0.544 64.548 0.845 0.005 0.698 1.778 1.133 0.513 0.355 0.617 0.139 0.165 1.361

India 4.036 0.029 4.092 3.980 8.759 0.608 60.777 0.897 0.072 0.774 1.778 1.159 0.674 0.252 0.685 0.175 0.111 0.979

Lebanon 2.392 0.044 2.479 2.305 9.478 0.530 66.149 0.474 -0.141 0.891 1.778 1.417 0.476 0.398 0.123 0.061 0.027 -0.110

Afghanistan 1.859 0.033 1.923 1.795 7.324 0.341 54.712 0.382 -0.081 0.847 1.778 0.645 0.000 0.087 0.000 0.093 0.059 0.976

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 20, 2023 at 10:49am

-

India is home to a quarter of the world’s hunger burden with nearly 224.3 million people undernourished in the country. The situation is even more dire among children under the age of five — 36.1 million are stunted, accounting for 31% being chronically malnourished.

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/voices/good-health-begins...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 21, 2023 at 8:23am

-

India is among the least happy countries in the world—worse than even war-hit Ukraine

ndia is also worse off than neighbors like Nepal, China, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and others

https://qz.com/india-is-less-happy-than-even-war-hit-ukraine-185024...

India has been one of the least happy countries in the world in recent years.

It was ranked 126 out of 137 countries surveyed, according to the 2023 edition of the World Happiness Report released yesterday (March 20). It was placed worse than neighbors like Nepal, China, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and others. The country is worse off than even war-hit Ukraine.

The annual report for the 2020-2022 time period uses life evaluations from the Gallup World Polls, which survey a representative sample of adults from every country, to arrive at its conclusions.

A lack of social support and connections among citizens during the covid-19 pandemic has been identified as the key reason for Indians being so gloomy. The pandemic-induced lockdown left millions of Indians stuck in social isolation, leading up to stress and depression.

Experts said that a lack of social connections over long periods of time, along with severe unemployment, high inflation scenario and healthcare worries, took a toll on people’s mental health.

“While people in India were least likely to have had daily interactions with nearby friends or family, at 58%, they were among the most likely to say they had interacted with friends or family who live far away (42%),” the State of Social Connections study by Gallup, Meta, and academic advisers in 2022 stated. Moreover, there was no notable relationship between households and social support in India.

About 55% of Indian women said they “never” interacted with people from work or school in the past seven days, compared to 33% of men. Even social media platforms were of little help to Indians.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 27, 2023 at 7:36am

-

Is India's Rise Actually Good for the West?

https://globelynews.com/south-asia/is-indias-rise-actually-good-for...

India has also used the moment (G20 summit) to finger-point at Europe, rather than condemn Russian aggression. Last year, India’s foreign minister, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, said, “Europe has to grow out of the mindset that Europe’s problems are the world’s problems.”

Jaishankar’s critique of Eurocentrism has merit. It’s also shared by many in the Global South, who bristle as the West has committed well over $100 billion in aid to Ukraine, but falls short in addressing challenges like climate change, the debt crisis, and food insecurity that are hurting poorer countries. Many of these problems have been exacerbated by the Russia-Ukraine war.

India has rightly put these issues on the G20 agenda this year. But it’s actually doing little more than paying lip service to them. The G20 finance ministers’ meeting last month concludedwithout any tangible commitments to debt-distressed countries like Sri Lanka.

In reality, India is using the G20 presidency and other global platforms to engage in sanctimonious posturing to gain space for the naked pursuit of its self-interest. It’s also leveraging them to project Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s image as a Hindu strongman at home.

India is no ally of the West or the Global South. It is a selective partner only out for itself. It seeks a multipolar world order in which the power of the West is diminished. Paradoxically, the U.S. and its allies are aiding India in reducing their global influence.

Policy elites in Washington and other Western capitals must come to terms with this reality. Naively, they see India’s rise as a world power as an indisputable good in countering China, so much that they ask for little in return. They give India the benefit of the doubt, even when it so brazenly pursues its interest at odds with their own.

If the behavior of India isn’t telling enough, its words are loud and clear. Jaishankar — India’s chief grand strategist — writes in his 2020 book that India should focus on “advancing national interests by identifying and exploiting opportunities created by global contradictions.” A top advisor to Modi, Jaishankar promotes a commitment-free foreign policy, arguing that India should leverage “competition to extract as much gains from as many ties as possible.” In other words, India is playing all sides against one another.

To its detriment, the West gives India easy wins without asking it to make real sacrifices or protect human rights. Its indulgence of India’s grandstanding and flaccid responses to taunting by Jaishankar and others also furthers Modi’s domestic Hindu nationalist agenda.

It allows Modi to not only project India as a “vishwa guru” or “world teacher,” but also furthers his own image as a mighty Hindu who is humbling the West and can act with impunity. Indeed, as civic and religious freedoms erode in India, Western governments balk at condemnation let alone punitive action.

The domestic symbolism of India’s global theatrics is lost on Western leaders. This is partly because the U.S. and other Western countries have failed to develop the institutional knowledge of the Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) ideology, lexicon, and networks. By contrast, there’s tremendous work on the Chinese Communist Party.

Case in point, when Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong cited India as a “civilizational power” this month, she inadvertently endorsed the BJP’s idea of a Hindu civilization or a “Hindu Rashtra,” in which Muslims are debased and erased.

Sadly, Western officials allow themselves to imagine a world in which the Hindutva ideology does not exist. They continue to proclaim that they are bound with India by “shared values,” as German Chancellor Olaf Scholz did last month, ignoring India’s very blatant authoritarian, majoritarian turn.

There is much to worry about when it comes to India’s future course. But the West is simply choosing to look away.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 29, 2023 at 4:34pm

-

See new Tweets

Conversation

S.L. Kanthan

@Kanthan2030

China is the world’s #1 manufacturer of cars and the #2 exporter of cars.

And China’s #1 customer is… Putin! I mean, Russia.

The U.S. and its non-sovereign puppet continent known as Europe must understand that the world has become more self-sufficient and resilient.

The “Ameripeans” cannot sanction or bomb other countries into submission anymore.

https://twitter.com/Kanthan2030/status/1641167244385452037?s=20

-------

China closes gap with Japan after 2022 car exports surpass Germany with 54.4 per cent surge to 3.11 million vehicles | South China Morning Post

https://www.scmp.com/business/china-business/article/3206875/chinas...

China has surpassed Germany to become the world’s second-largest car exporter after mainland exports jumped 54.4 per cent year on year to 3.11 million vehicles in 2022, according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM).The nation is also closing in on Japan’s export volume, and is likely to clinch the title of the world’s top car exporter in the coming few years, analysts said.According to MarkLines, an auto industry data provider, Japanese carmakers shipped 3.2 million vehicles abroad in the first 11 months of 2022, almost unchanged from a year earlier.In 2021, Japan exported 3.82 million cars, and it is expected to post a year-on-year decline once its full-year results are tallied.

Germany exported 2.61 million cars last year, up 10 per cent from 2021, according to the German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA).“The strong growth momentum in China’s car exports has helped the nation to earn a reputation as a powerful carmaker, as its passenger and commercial vehicles are well received by people outside the mainland,” said Cao Hua, a partner at private-equity firm Unity Asset Management. “China’s electric cars have won considerable market share in some developing nations and will eventually propel the country into the top position of the world’s major auto exporters.”

Exports accounted for 11.5 per cent of mainland China’s total 2022 production of passenger cars and commercial vehicles, which rose 3.4 per cent year on year to 27 million, according to the CAAM.

China’s car market, the world’s largest since 2009, has long been dominated by foreign brands such as Volkswagen, General Motors, BMW and Mercedes-Benz.However, the country’s indigenous brands, such as BYD and Geely, are accelerating a global push, supported by a robust automotive supply chain.Electric vehicles (EVs) have become a significant factor in China’s buoyant car exports, with EV shipments surging 120 per cent year on year to 679,000 in 2022, the CAAM data showed.

Citic Securities forecast in a research report last month that China’s car export volume could hit 5.5 million units in 2030, of which 2.5 million cars would be electric.UBS analyst Paul Gong said that Chinese EV builders have been racing ahead of their Japanese and South Korean rivals to tap Southeast Asian markets and also have plans to set up production bases and promote their vehicles there.“It is not just the beginning of the Chinese carmakers’ global push,” said Gong. “They are already the established market leaders in some Southeast Asian countries.”

BYD, backed by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, dethroned Tesla as the world’s largest EV maker in the second quarter of 2022.In mid-October, the company launched its first passenger vehicle in India, the Atto 3 electric sport utility vehicle, to spur overseas sales. It is now selling its cars in multiple overseas markets including Norway, Singapore and Brazil.BYD is also considering building a battery plant in the United States but does not currently plan to sell its electric cars there, according to a Bloomberg news report.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 30, 2023 at 8:48am

-

Can #India replace #China as a pillar of #global #economy? @NickKristof doubts it. A 9th grader in #Kolkata can not do simple multiplication. School absenteeism is rampant in #Rajasthan. China thrives because it made huge #investments in #humancapital. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/29/opinion/india-economic-growth.html

In conversations with young Indian women, I hear again and again about the barriers they face that their brothers don’t. It’s difficult for single women to rent apartments, it’s considered inappropriate for them to be out in the evening, and they are subjected to a blizzard of sexual harassment, which persists because of a culture of impunity.

Yet I wonder if that, too, isn’t changing. India has more strong, independent women than ever, and they are forcing change.

--------

As for the I.T. sector, it’s dazzling and in some respects ahead of the United States. Here in India, digital data on mobile phones is extremely cheap, and you can buy a mango from a street vendor with your phone. Digital transactions are everywhere, and people easily keep digital records securely on their phones.

Nandan Nilekani, a pioneer in information services, says that India’s digital public infrastructure enables a technology-led growth model, and there are indeed signs of a boom in entrepreneurial activity in the tech sector: India had 452 start-ups in 2016 and 84,000 last year.

But it is export-led manufacturing that traditionally has provided the path for economic breakout in Asia because it can employ an enormous number of people. In India, manufacturing’s share of the economy has stagnated, and international executives share horror stories about red tape and the difficulty of doing business.

“The point of manufacturing is really job creation,” noted Alyssa Ayres, an India specialist at George Washington University, and that isn’t happening much. “People are worried about why the needle isn’t moving.”

India has had false dawns before. For a while in the 2000s, it was enjoying economic growth rates of roughly 8 percent per year, and it seemed that it might become the next Asian tiger economy. In 2010, The Economist published a cover story, “How India’s Growth Will Outpace China’s.”

Today India has a new chance to lure manufacturers. China has an aging population, its brand is tarnished by repression, and global companies are eager to find new manufacturing bases. India has English speakers, a familiar legal system, low-cost workers and first-rate engineers emerging from the Indian Institutes of Technology.

--------

Arvind Subramanian, a former economic adviser to the government of India who is now at Brown University, is skeptical that India will change its policies enough to seize the opportunity presented by China’s difficulties. But he thinks Apple’s efforts to manufacture iPhones in India offer a ray of hope by encouraging other companies to follow.

“The entry of Apple is significant — that is the space to watch,” he said. “If Apple thinks India can be a competitive place from which to export to the world, there could be demonstration effects.”

-----------

If India can boost education, free its women to join the labor force and attract the companies that are desperate to find new bases for manufacturing, it can surprise us again.

If it can do that, it will recover its historical role as an economic powerhouse, and the past few centuries of poverty will be forgotten — a blink of the eye in the context of India’s ancient civilization. It would again be normal to think of India as a great power and one of the pillars of the global economy, and that would change the world.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 30, 2023 at 10:46am

-

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 30, 2023 at 10:47am

-

India is Broken

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3215379/hype-over-indi...

by Ashoka Mody

Since the liberalising reforms of the mid-1980s, the manufacturing sector’s share of GDP has fallen slightly to about 14 per cent, compared to 27 per cent in China and 25 per cent in Vietnam. India commands less than a 2 per cent global share of manufactured exports, and as its economy slowed in the second half of 2022, the manufacturing sector contracted further.

Yet it is through exports of labour-intensive manufactured products that Taiwan, South Korea, China and now Vietnam came to employ vast numbers of their people. India, with its 1.4 billion people, exports about the same value of manufactured goods as Vietnam does with 100 million people.

Those who believe that India stands at the cusp of greatness usually focus on two recent developments. First, Apple contractors have made initial investments to assemble high-end iPhones in India, leading to speculation that a broader move away from China by manufacturers will benefit India despite the country’s considerable quality-control and logistical problems.

while such an outcome is possible, academic analysis and media reports are discouraging. Economist Gordon H. Hanson says Chinese manufacturers will move labour-intensive manufacturing from the country’s expensive coastal hubs to its less-developed interior, where production costs are lower.

Moreover, investors moving out of China have gone mainly to Vietnam and other countries in Southeast Asia, which like China are members of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. India has eschewed membership in this trade bloc because its manufacturers fear they will be unable to compete once other member states gain easier access to the Indian market.

As for US producers pulling away from China, most are “near-shoring” their operations to Mexico and Central America. Altogether, while some investment from this churn could flow to India, the fact remains that inward foreign investment fell year on year in 2022.

The second source of hope is the Indian government’s Production-Linked Incentive Schemes, which were introduced in early 2021 to offer financial rewards for production and jobs in sectors deemed to be of strategic value. Unfortunately, as former Reserve Bank of India governor Raghuram G. Rajan and his co-authors warn, these schemes are likely to end up merely fattening corporate profits like previous sops to manufacturers.

India’s run with start-up unicorns is also fading. The sector’s recent boomrelied on cheap funding and a surge of online purchases by a small number of customers during the pandemic. But most start-ups have dim prospects for achieving profitability in the foreseeable future. Purchases by the small customer base have slowed and funds are drying up.

Looking past the illusion created by India’s rebound from the pandemic, the country’s economic prognosis appears bleak. Rather than indulge in wishful thinking and gimmicky industrial incentives, policymakers should aim to power economic development through investments in human capital and by bringing more women into the workforce.

India’s broken state has repeatedly avoided confronting long-term challenges and now, instead of overcoming fundamental development deficits, officials are seeking silver bullets. Stoking hype about an imminent Indian century will merely perpetuate the deficits, helping neither India nor the rest of the world.

Ashoka Mody, visiting professor of international economic policy at Princeton University, is the author of India is Broken: A People Betrayed, Independence to Today. Copyright: Project Syndicate

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 30, 2023 at 6:58pm

-

Emerging-market stocks fall behind as #China and #India disappoint. India, with a 13% weighting in the emerging-markets index, has been a drag, with its stocks in the index down more than 8% from the end of 2022. #Adaniscam #Modi - Nikkei Asia

https://twitter.com/haqsmusings/status/1641611381668712450?s=20

-------

https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Markets/Emerging-market-stocks-fal...

India, with a 13% weighting in the emerging-markets index, has also been a drag, with its stocks in the index down more than 8% from the end of 2022.

Prospects for medium- to long-term growth on the back of an expanding population had helped make India a popular investment alternative to China, lifting the benchmark Sensex index to a record high in December. But concerns are growing over deceleration in the short term.

"India's economy would be considered to be in a recession by developed-economy standards," said Toru Nishihama at the Dai-ichi Life Research Institute. Though the economy grew 4.4% on the year in real terms in the fourth quarter of 2022, seasonally adjusted GDP shrank on an annualized basis for a second straight quarter.

High inflation has forced the Reserve Bank of India to hike interest rates even at the risk of chilling the economy. While the International Monetary Fund expects India's economy to grow 6.1% for the year starting in April, private-sector forecasts are more pessimistic, with HSBC expecting a slowdown to 5.5%.

More broadly, fears that tightening credit conditions amid the recent banking turmoil could bring on a global downturn are putting downward pressure on shares, especially in resource exporters like Brazil and the United Arab Emirates. The Refinitiv/CoreCommodity CRB index, a broad measure of international commodity price trends, sank to its lowest in more than a year in mid-March.

Market watchers had harbored high hopes for emerging economies this year.

Morgan Stanley said in November that emerging-market stocks would emerge from their longest-ever bear run this year, with the MSCI index up 12% compared with a 1% fall for the S&P 500. It anticipated that slowing inflation and a rebound from the impact of the strong dollar last year would spur Asian countries in particular to lead a global economic recovery.

Emerging-market equity funds saw net inflows of $37.2 billion between early December, when capital began moving back in that direction, and late March. But the pace has slowed sharply, from $29.4 billion in the first two months to $7.8 billion since February. The week of March 10, which brought the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, saw a net outflow of $65.94 million.

Despite this, a Bank of America survey of institutional investors this month found that nearly 40% were overweight emerging-market stocks, making it the second-most-popular trade behind cash. U.S. stocks, by contrast, were the top target for underweighting.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on April 3, 2023 at 5:20pm

-

From fast food to autos, India's digitally connected users lure investors

https://www.reuters.com/world/india/fast-food-autos-indias-digitall...

India's per capita consumption of food was at $314 in 2020 compared to $884 for China, while that of clothing stood at $53.9 versus $212.9 for China, data from CLSA showed. Per capita spending on health related items in India was $56.8 in 2020 and $389.3 for China, the data showed.

"A pattern will continue to repeat for years in India: industry after industry emerging from a long period of under-penetration" and moving up the per capita consumption scale, said Vikas Pershad, portfolio manager for Asian equities at M&G Investments.

"The range of industries will span healthcare delivery (hospitals) to cars and two-wheelers to housing finance companies and cement."

As the incomes and wealth of Indians rise, their aspirational needs will see demand ramp up for packaged food and beverages, branded goods, travel, preventive healthcare, and personal care, said ICICI Prudential's Khandelwal and the fund's chief investment officer S Naren.

FOREIGN INVESTORS JUMP IN

With private consumption accounting for 60% of India's $3.5 trillion GDP, foreign portfolio investors have been quick to latch on.

They pumped in a net $2.7 billion in four key consumption sectors - automobiles, consumer durables, consumer services and FMCG, in the first 11 months of the financial year 2022-23 (April-March), according to data from India's National Securities Depository Ltd.

In contrast, the broader Indian equity markets saw an outflow of $5.9 billion.

To be sure, it has not been all smooth sailing for investors as they chased India's consumption boom. Shares of the new-age technology companies have tumbled since their listings, and while they now trade at more reasonable valuations, they are still pricey compared to the industry median.

And most traditional consumer-focused companies also trade at valuations above the benchmark index.

Indian equities remain quite expensive both on a historical and relative basis, compared to China, for instance, said David Chao, global market strategist at Invesco Asia Pacific, who sees "outsized" growth in segments like quick service restaurants and consumer durables.

But investors have to look beyond that, he said. "To be an investor and make money in India, you have to take a longer time horizon."

Comment

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Pakistani Prosthetics Startup Aiding Gaza's Child Amputees

While the Israeli weapons supplied by the "civilized" West are destroying the lives and limbs of thousands of Gaza's innocent children, a Pakistani startup is trying to provide them with free custom-made prostheses, according to media reports. The Karachi-based startup Bioniks was founded in 2016 and has sold prosthetics that use AI and 3D scanning for custom designs. …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on July 8, 2025 at 9:30pm

Indian Military Begins to Accept Its Losses in "Operation Sindoor" Against Pakistan

The Indian military leadership is finally beginning to slowly accept its losses in its unprovoked attack on Pakistan that it called "Operation Sindoor". It began with the May 31 Bloomberg interview of the Indian Chief of Defense Staff General Anil Chauhan in Singapore where he admitted losing Indian fighter aircraft to Pakistan in an aerial battle on May 7, 2025. General Chauhan further revealed that the Indian Air Force was grounded for two days after this loss. …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on July 5, 2025 at 10:30am — 5 Comments

© 2025 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

No silver bullet that will fix weak job creation, a small, uncompetitive #manufacturing sector & gov’t schemes fattening corporate profits

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3215379/hype-over-indi...

by Ashoka Mody

Indian elites are giddy about their country’s economic prospects, and that optimism is mirrored abroad. The International Monetary Fund forecasts that India’s GDP will increase by 6.1 per cent this year and 6.8 per cent next year, making it one of the world’s fastest-growing economies.

Other international commentators have offered even more effusive forecasts, declaring the arrival of an Indian decade or even an Indian century.

In fact, India is barrelling down a perilous path. All the cheerleading is based on a disingenuous numbers game. More so than other economies, India’s yo-yoed in the three calendar years from 2020 to 2022, falling sharply twice with the emergence of Covid-19 and then bouncing back to pre-pandemic levels. Its annualised growth rate over these three years was 3.5 per cent, about the same as in the year preceding the pandemic.

Forecasts of higher future growth rates are extrapolating from the latest pandemic rebound. Yet, even with pandemic-related constraints largely in the past, the economy slowed in the second half of 2022, and that weakness has persisted this year. Describing India as a booming economy is wishful thinking clothed in bad economics.

Worse, the hype is masking a problem that has grown in the 75 years since independence: anaemic job creation. In the next decade, India will need hundreds of millions more jobs to employ those who are of working age and seeking work. This challenge is virtually insurmountable considering that the economy failed to add any net new jobs in the past decade, when 7 million to 9 million new jobseekers entered the market each year.

This demographic pressure often boils over, fuelling protests and episodic violence. In 2019, 12.5 million people applied for 35,000 job openings in the Indian railways – one job for every 357 applicants. In January 2022, railway authorities announced they were not ready to make the job offers. The applicants went on a rampage, burning train cars and vandalising railway stations.

With urban jobs scarce, tens of millions of workers returned during the pandemic to eking out meagre livelihoods in agriculture, and many have remained there. India’s already-distressed agriculture sector now employs 45 per cent of the country’s workforce.

Farming families suffer from stubbornly high underemployment, with many members sharing limited work on plots rendered steadily smaller through generational subdivision. The epidemic of farmer suicides persists. To those anxiously seeking support from rural employment-guarantee programmes, the government unconscionably delays wage payments, triggering protests.

For far too many Indians, the economy is broken. The problem lies in the country’s small and uncompetitive manufacturing sector.