PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

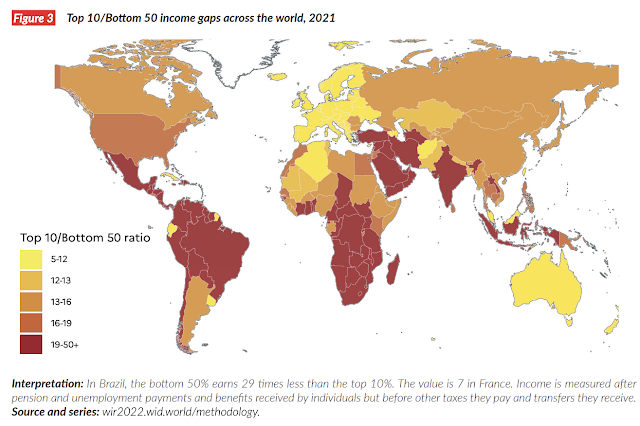

India Is Among The World's Most Unequal Countries

India is one of the most unequal countries in the world, according to the World Inequality Report 2022. There is rising poverty and hunger. Nearly 230 million middle class Indians have slipped below the poverty line, constituting a 15 to 20% increase in poverty. India ranks 94th among 107 nations ranked by World Hunger Index in 2020. Other South Asians have fared better: Pakistan (88), Nepal (73), Bangladesh (75), Sri Lanka (64) and Myanmar (78) – and only Afghanistan has fared worse at 99th place. Meanwhile, the wealth of Indian billionaires jumped by 35% during the pandemic.

|

| Income Inequality Map. Source: World Inequality Report 2022 |

Unemployment Crisis:

India lost 6.8 million salaried jobs and 3.5 million entrepreneurs in November alone. Many among the unemployed can no longer afford to buy food, causing a significant spike in hunger. The country's economy is finding it hard to recover from COVID waves and lockdowns, according to data from multiple sources. At the same time, the Indian government has reported an 8.4% jump in economic growth in the July-to-September period compared with a contraction of 7.4% for the same period a year earlier.

|

| Income Inequality By Regions. Source: World Inequality Report 2022 |

|

| Income & Wealth Inequality. Source: World Inequality Report 2022 |

Rising Poverty:

Nearly 230 million middle class Indians have slipped below the poverty line, constituting a 15 to 20% increase in poverty since Covid-19 struck last year, according to Pew Research. Middle class consumption has been a key driver of economic growth in India. Erosion of the middle class will likely have a significant long-term impact on the country's economy. “India, at the end of the day, is a consumption story,” says Tanvee Gupta Jain, UBS chief India economist, according to Financial Times. “If you never recovered from the 2020 wave and then you go into the 2021 wave, then it’s a concern.”

Increasing Hunger:

A United Nations report on inequality in Pakistan published in April 2021 revealed that the richest 1% Pakistanis take 9% of the national income. A quick comparison with other South Asian nations shows that the 9% income share for the top 1% in Pakistan is lower than 15.8% in Bangladesh and 21.4% in India. These inequalities result mainly from a phenomenon known as "elite capture" that allows a privileged few to take away a disproportionately large slice of public resources such as public funds and land for their benefit.

|

| Income Distribution by Quintiles in Pakistan. Source: UNDP |

Elite Capture:

Elite capture, a global phenomenon, is a form of corruption. It describes how public resources are exploited by a few privileged individuals and groups to the detriment of the larger population.

A recently published report by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) has found that the elite capture in Pakistan adds up to an estimated $17.4 billion - roughly 6% of the country's economy.

Pakistan's most privileged groups include the corporate sector, feudal landlords, politicians and the military. The UN Development Program's NHDR for Pakistan, released last week, focused on issues of inequality in the country of 220 million people.

Ms. Kanni Wignaraja, assistant secretary-general and regional chief of the UNDP, told Aljazeera that Pakistani leaders have taken the findings of the report “right on” and pledged to focus on prescriptive action. “My hope is that there is strong intent to review things like the current tax and subsidy policies, to look at land and capital access", she added.

| Inequality in Pakistan. Source: UNDP |

Income Inequality:

The richest 1% of Pakistanis take 9% of the national income, according to the UNDP report titled "The three Ps of inequality: Power, People, and Policy". It was released on April 6, 2021. Comparison of income inequality in South Asia reveals that the richest 1% in Bangladesh and India claim 15.8% and 21.4% of national income respectively.

In addition to income inequality, the UNDP report describes the inequality of opportunity in terms of access to services, work with dignity and accessibility. It is based on exhaustive statistical analysis at national and provincial levels, and includes new inequality indices for child development, youth, labor and gender. Qualitative research, through focus groups with marginalized communities, has also been undertaken, and the NHDR 2020 Inequality Perception Survey conducted. The NHDR 2020 has been guided by a diverse panel of Advisory Council members, including policy makers, development practitioners, academics, and UN representatives.

Summary:

Neoliberal policies in emerging markets like India have spurred economic growth in last few decades. However, the gains from this rapid growth have been heavily skewed in favor of the rich. The rich have gotten richer while the poor have languished. The average per capita income in India has tripled in recent decades but the minimum dietary intake has fallen. According to the World Food Program, a quarter of the world's undernourished people live in India. The COVID19 pandemic has further widened the gap between the rich and poor.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

Indian Economy Grew Just 0.2% Annually in Last Two Years

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

Pakistan's 2012 GDP Estimated at $401 Billion

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid1...

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Cou...

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan's Sehat Card Health Insurance Program

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

COVID Lockdown Decimates India's Middle Class

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

How Has India Built Large Forex Reserves Despite Perennial Trade De...

India's Unemployment and Hunger Crises"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on April 18, 2022 at 11:02am

-

Why some Indians die younger than others

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-61091336

People belonging to the country's most marginalised social groups - adivasis or indigenous people, Dalits (formerly known as untouchables) and Muslims - are more likely to die at younger ages than higher-caste Hindus, according to one paper by Sangita Vyas, Payal Hathi and Aashish Gupta.

They examined official health survey data of more than 20 million people from nine Indian states accounting for about half of India's population of 1.4 billion.

---------------

Here's the average lifespan of disadvantaged men: 60 years for adivasis, 61.3 for Dalits, and 63.8 for Muslims. An average higher-caste Hindu man is expected to live for 64.9 years.

Such enduring gaps were comparable in terms of years to the gaps in life expectancies between black and white Americans in the US, researchers say. Since life expectancy in India is less than four-fifths the level in the US, the outcomes in India are more substantial in percentage terms.

To be sure, buoyed by advances in medicine, hygiene and public health, India has made massive gains in life expectancy: half a century ago, the average Indian would beat the odds by surviving into his or her 50s. Now they're expected to live almost 20 years longer.

Dalit women are among the most oppressed in the world

The bad news is that although life expectancy for all social groups has increased, disparities have not reduced, according to a related study by Aashish Gupta and Nikkil Sudharsanan.

In some cases, absolute disparities have increased: the life expectancy gap between Dalit men and upper-caste Hindu men, for example, had actually increased between the late 1990s and mid-2010s. And although Muslims had a modest life expectancy disadvantage compared to high castes in 1997-2000, this gap has grown substantially over the past 20 years.

India is home to some of the largest populations of marginalised social groups in the world. The 120 million adivasis - an "invisible and marginal minority", in the words of a historian - live in considerable poverty in some of the remotest parts. Despite political and social empowerment, the 230 million Dalits continue to face discrimination. And an overwhelming majority of 200 million Muslims, the third largest number of any country, continue to languish at the bottom of the social ladder and often become targets of sectarian violence.

What explains these gaps in life expectancy in different groups?

India is neither a melting pot nor a salad bowl

Here is where it gets interesting.

Researchers find that differences in where people live, their wealth and exposure to environment account for less than half of these gaps. For example, the study found that adivasis and Dalits live shorter than higher-caste Hindus across wealth categories.

To find more precise answers on how discrimination influences mortality, India needs to step up research. There is some evidence which tells us why, for example, Muslims live longer than the adivasis and Dalits. They include lower exposure to open defecation among children, lower rates of cervical cancers among women, lower consumption of alcohol and lower incidence of suicide.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 29, 2022 at 6:03pm

-

What’s the Average Salary in Pakistan in 2022?

https://biz30.timedoctor.com/average-salary-in-pakistan/

The average salary in Pakistan is 81,800 PKR (Pakistani Rupee) per month, or around USD 498 according to the exchange rates in August 2021.

The Pakistan average is significantly lower than the US average (USD 7,900) but comparable to India (USD 430), Ukraine (USD 858), and the Philippines (USD 884). It’s one of the many reasons why Pakistan is a viable alternative to these popular outsourcing destinations.

However, you’ll need a more comprehensive analysis to understand the total expenditure on a Pakistani employee.

In this article, we’ll share vital figures and comparisons related to the average salary in Pakistan. We’ll also explore the country’s payroll rules and top reasons to outsource there.

Average Salary in Pakistan: Key Figures

The average salary figure for a country is the sum of the salaries of the working population divided by the total number of employees. It may also include benefits such as housing, transport allowance, insurance, etc., on top of the employee’s basic salary.

The average salary is usually a good indicator of the typical income of a working citizen in the country.

Here are some key salary figures for Pakistan according to Salary Explorer, a salary comparison website:

The average remuneration in Pakistan may vary between 20,700 PKR per month (average minimum salary) and 365,000 PKR per month (maximum average). Please remember that this is an average salary range, and the actual maximum salary may be higher.

The median salary in Pakistan is 76,900 PKR per month.

If we sort the employee salaries in Pakistan in ascending or descending order, the median represents the central point in the distribution. In other words, half the Pakistani employees earn more than 76,900 PKR per month, while the other half earn less.

These national average salary figures may give you a general estimate and help compare expenditure on employee salaries among different countries.

But it won’t help you determine the exact remuneration for each employee in your company.

For that, you’ll need to consider other factors like

The type of industry.

Years of experience and qualification of the employee.

The kind of work: entry level, professional, etc.

The mode of work: full-time, part-time, remote, etc.

The region where you are operating.

The cost of living in the country.

So let’s take a more comprehensive look at the salary information in Pakistan.

A. Average Salary by Industry

The average salary in a country may vary significantly with the type of industry.

Pakistan is known for its cotton, textile, and agriculture exports, and these industries have a significant share in the country’s GDP. Due to this reason, the manufacturing sector usually employs a large portion of the Pakistani workforce.

Here’s an industry-wise breakdown of the average salaries in Pakistan:

Industry Average Monthly Salary

Energy 73,600 PKR

Information Technology 82,100 PKR

Healthcare 122,000 PKR

Real Estate 92,600 PKR

Media / Broadcasting 75,200 PKR

Telecommunication 72,100 PKR

Source: salaryexplorer.com

B. Average Salary by Region

While the capital city of Islamabad is the administrative center of the country, Karachi and Lahore are the major commercial hubs in Pakistan.

The average employee salary in the country depends on which city you’re operating in.

Here’s the salary report for major Pakistani cities:

City Average Monthly Salary

Karachi 88,300 PKR

Lahore 86,800 PKR

Islamabad 76,400 PKR

Faisalabad 85,400 PKR

Source: salaryexplorer.com

C. Salary Variations by Education

As a general rule of thumb, a Pakistani employee with higher educational degrees gets a higher pay scale than their peers with a lesser degree for the same type of work.

But how does the pay scale change with the education level?

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 29, 2022 at 6:05pm

-

Riaz Haq has left a new comment on your post "India in Crisis: Unemployment and Hunger Persist After Waves of COVID":

Earning Rs 25,000 monthly puts one in India's top 10%: Inequality report

Salaried employees who file income taxes are relatively better off, says study that recommends an urban employment scheme.

https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/earning-rs...

An Indian making Rs 3 lakh a year would be placed in the top 10 per cent of the country’s wage earners. The data is part of The State of Inequality in India report prepared by the India arm of a global competitiveness initiative, the Institute for Competitiveness.

Bibek Debroy, chairman of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister released it on Wednesday. The report recommended a scheme for the urban jobless and universal basic income as means to reduce inequality. The nature of one's work may make a difference to income shows a closer look at the numbers in ...

--------------------

If You Earn Rs 25,000 Per Month, You're Among India's Top 10% Income Earners

https://www.indiatimes.com/news/india/if-you-earn-rs-25000-per-mont...

The State of Inequality in India report prepared by the India arm of a global competitiveness initiative, the Institute for Competitiveness, sheds light on the state of gross inequality in the country. Ninety per cent of Indians do not earn even Rs 25,000 per month.

This highlights the failure of the trickle-down approach to economic growth.

Bibek Debroy, chairman of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister released it on Wednesday.

The report gives a comprehensive overview of the state of inequality in the country by looking at various indicators like income profile, labour market dynamics, health, education, and household amenities.

The report mooted an urban jobs scheme and universal basic income as a means to reduce inequality in the country.

Gaping income disparity

Extrapolation of the income data from Periodic Labour Force Survey 2019-20 has shown that a monthly salary of Rs 25,000 is already amongst the top 10% of total incomes earned, pointing towards some levels of income disparity, the report said.

It further highlighted that the average monthly salary of regular salaried, wage earners in July-September 2019 amounted to Rs 13,912 for rural males and Rs 19,194 for urban males. Employed females in rural parts earned Rs 12,090 in the same period while females in urban India earned an average Rs 15,031.

India’s income profile is outlined by a growing disparity between those who lie on the top end of the earning pyramid and those on the bottom, highlighting the failure of the trickle-down approach to economic growth.

Top 1% earn nearly thrice as much as the bottom 10%

According to the Annual Report of the PLFS 2019- 20, the annual cumulative wages came to be around Rs 18,69,91,00,000, out of which the top 1 per cent earned nearly Rs 1,27,48,00,000, and the bottom 10 per cent accounted for Rs 32,10,00,000 indicating that the top 1 per cent earns almost thrice as much as the bottom 10 per cent.

Meanwhile, the bottom 50% of the pyramid held approximately 22% of the total income earned across the three-time periods. The growth rate of the bottom 50% has been at 3.9% from 2017-18 to 2019-20, while the top 10% has grown by 8.1%.

“This highlights the disparity between the income groups and the disproportionate rate of growth among these tiers. Additionally, the top 1% grew by almost 15% between 2017- 18 to 2019-20, whereas the bottom 10% registered a close to 1% fall,” the report highlighted.

In terms of workforce share, nearly 15 per cent of the entire workforce earns less than Rs 50,000 (less than Rs 5,000 a month), in both years, exacerbating the experiences of poverty and economic inequality.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 31, 2022 at 7:58am

-

Multiple faces of #inequality in #India. Known for its #caste system, India is often thought of as one of the world's most unequal countries. Top 10% take 57% of national income—higher than 50% during British Raj. Bottom half get only 13% https://phys.org/news/2022-05-multiple-inequality-india.html via @physorg_com

Known for its caste system, India is often thought of as one of the world's most unequal countries. The 2022 World Inequality Report (WIR), headed by leading economist Thomas Piketty and his protégé, Lucas Chancel, did nothing to improve this reputation. Their research showed that the gap between the rich and the poor in India is at a historical high, with the top 10% holding 57% of national income—more than the average of 50% under British colonial rule (1858–1947). In contrast, the bottom half accrued only 13% of national revenue. A February report by Oxfam noted 2021 alone saw 84% of households suffer a loss of income while the number of Indian billionaires grew from 102 to 142.

Both reports highlight not only the problem of revenue inequality but also of opportunity. While there may be disagreement between left and right on the ethics of equality, there is a consensus that everyone should be given the chance to succeed and the principle of fairness—and not factors such as birth, region, race, gender, ethnicity or family backgrounds—ought to lay the foundations of a level playing field for all.

Drawing from the latest pre-pandemic database from the Periodic Labor Force Survey of 2018–19, our research confirms this is far from the case in India. On the one hand, the country has had a consistently high GDP growth rate of more than 7% for nearly two decades, the exception being the period around the 2008 financial crisis. On the other hand, this income has failed to trickle down to India's marginalized communities, with preliminary results pointing to a higher level of inequality of opportunity in the country than in Brazil or Guatemala.

Precarity as well as a large shadow economy also plague the country's labor market. Even before the pandemic, only 30% to 40% of regular salaried adult Indian earners had job contracts or social securities such as national pension schemes, provident fund or health insurance. For self-employed workers, the situation is even more critical, even though these constituted nearly 60% of the Indian labor force in 2019.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 31, 2022 at 7:58am

-

Multiple faces of #inequality in #India. Known for its #caste system, India is often thought of as one of the world's most unequal countries. Top 10% take 57% of national income—higher than 50% during British Raj. Bottom half get only 13% https://phys.org/news/2022-05-multiple-inequality-india.html via @physorg_com

Castes, gender and background still determine life chances

Our research indicated that at least 30% of earning inequality is still determined by caste, gender and family backgrounds. The seriousness of this figure becomes clear when it's compared with rates of the world's most egalitarian countries, such as Finland and Norway, where the respective estimates are below 10% for a similar set of social and family attributes.

The caste system is a distinctive feature of Indian inequality. Emerging around 1500 BC, the hereditary social classification draws its origins from occupational hierarchy. Ancient Indian society was thought to be divided in four Varnas or castes: Brahmins (the priests), Khatriyas (the soldiers), Vaishyas (the traders) and Shudras (the servants), in order of hierarchy. Apart from the above four, there were the "untouchables" or Dalits (the oppressed), as they are called now, who were prohibited to come into contact with any of the upper castes. These groups were further subdivided in thousands of sub-castes or Jatis, with complicated internal hierarchy, eventually merged into fewer manageable categories under the British colonization period.

The Indian constitution secures the rights of the Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST) and Other Backward Class (OBC) through a caste-based reservation quota, by virtue of which a certain portion of higher-education admissions, public sector jobs, political or legislative representations, are reserved for them. Despite this, there is a notable earning inequality between these social categories and the rest of the population, who consists of no more than 30% to 35% of Indian population. Adopting a data-driven approach we find that, on average, SC, ST and OBC still earn less than the rest.

While unique, the caste system is not the only source of unfairness. Indeed, it accounts for less than 7% of inequality of opportunity, something that's in itself laudable. We will need to add criteria such as gender and family background differences to explain 30% of inequality.

In a country where femicides and rapes regularly make headlines, it comes as no surprise that women from marginalized social groups are often subject to a "double disadvantage." For some states such as Rajasthan (in the country's northwest), Andhra Pradesh (south), Maharashtra (center), we find even upper-caste women enjoy fewer educational opportunities than men from the marginalized SC/ST communities. Even among the graduates, while the national average employment rate for males is 70%, it is below 30% for the females.

A temporary byproduct of rising growth?

Rising inequality could be dismissed as a temporary byproduct of rapid growth on the grounds of Simon Kuznets' famous hypothesis, according to which inequality rises with rapid growth before eventually subsiding. However, there is no guarantee of this, least of all because widening gap between rich and poor is not only limited to fast-growing countries such as India. Indeed, a 2019 study found that the growth-inequality relationship often reflects inequality of opportunity and prospects of growth are relatively dim for economies with a bumpy distribution of opportunities.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 31, 2022 at 7:59am

-

Multiple faces of #inequality in #India. Known for its #caste system, India is often thought of as one of the world's most unequal countries. Top 10% take 57% of national income—higher than 50% during British Raj. Bottom half get only 13% https://phys.org/news/2022-05-multiple-inequality-india.html via @physorg_com

Despite sporadic evidence of converging caste or gender gaps, our research shows an intricate web of social hierarchy has been cast over every aspect of life in India. It is true that some deprived castes may withdraw from school early to explore traditional jobs available to their caste-based networks—thereby limiting their opportunities. However, are they responsible for such choices or it is the precariousness of the Indian economy that pushes them down such routes? There is no straightforward answer to these questions, even if some of the "bad choices" that individuals make can result more from pressure than choice.

Given the complicated intertwining of various forms of hierarchy in India, broad policies targeting inequality may have less success than anticipated. Dozens of factors other than caste, gender or family background feed into inequality, including home sanitation, school facilities, domestic violence, access to basic infrastructure such as electricity, water or healthcare, crime rates, political stability of the locality, environmental risks and many more.

Better data would allow researchers studying India to capture the contours of its society and also help gauge the effectiveness of policies intended to expand opportunities for the neediest.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on October 3, 2022 at 5:26pm

-

“The poverty in the country is standing like a demon in front of us. It is important that we slay this demon. That 20 crore people are still below poverty line is a figure that should make us very sad. As many as 23 crore people have less than Rs 375 income per day. There are four crore unemployed people in the country. The labour force survey says we have an unemployment rate of 7.6 per cent,” said Dattatreya Hosabale. Also Read - 23 Crore Indians Pushed Below Poverty Line Amid COVID-19 Pandemic, Says Study

https://www.india.com/business/23-cr-people-with-income-less-than-r...

He also spoke about the rising levels of economic inequality that the country is witnessing today. Acknowledging that India is among the top six economies of the world, he said top 1 per cent holds 1/5th (20 per cent) of the nation’s income. He added that 50 per cent of the country’s population has only 13 per cent of the country’s income. Hosabale went on to quote United Nations’ observations on the poverty and development in India. Also Read - Today Will be Your Last Working Day With Uber: Ride-hailing Firm Lays Off Nearly 3,700 Employees Via Zoom

“A large part of the country still does not have access to clean water and nutritious food. Civil strife and the poor level of education are also a reason for poverty. That is why a New Education Policy has been ushered in. Even climate change is a reason for poverty. And at places the inefficiency of the government is a reason for poverty.”

In his speech, Hosabale also stressed on the importance of creating an entrepreneurship-friendly environment apart from the need to carry skill-training from the urban to rural India.

“During Covid, we learnt that there is a possibility of generating jobs at the rural level according to local needs and using local talent. That is why the Swavalambi Bharat Abhiyan was launched. We don’t just need all-India level schemes, but also local schemes. It can be done in the field of agriculture, skill development, marketing etc. We can revive cottage industry. Similarly, in the field of medicine, a lot of Ayurvedic medicines can be manufactured at the local level. We need to find people interested in self-employment and entrepreneurship,” Hosabale said.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on January 22, 2023 at 8:15pm

-

The Squeeze on India’s Spenders Is Yet to Lift

Analysis by Andy Mukherjee | Bloomberg

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/the-squeeze-onindias-spende...

Manufacturing of wants is hard anywhere for marketers, but the challenge is bigger when the bottom half of the population takes home only 13% of national income. While India’s rapid economic growth since the 1990s has undoubtedly expanded the spending capacity of its 1.4 billion people, acute and rising inequality — among the worst in the world — makes for a notoriously budget-conscious median consumer. Companies can take nothing for granted: For Unilever’s local Indian unit, a late winter crimped sales of skin-care products last quarter.

Still, the maker of Dove body wash and Surf detergent managed to eke out an overall 5% increase in sales volume from a year earlier, lifting net income to 25.1 billion rupees ($309 million), slightly better than expected. That was achieved by price cuts — passing along the benefit of lower palm-oil costs to soap buyers — and a step up in promotion and advertising. Still, not all players have the market leader’s financial chops. Investors who look closely at Hindustan Unilever Ltd.’s earnings for a pulse on India’s consumer demand will note with dismay the slide in industry-wide volumes for cleaning liquids, personal care items and food, the categories in which the firm competes.

This isn’t new. Consumer demand in India has been moderating since August 2021. Village households, many of which had to liquidate their gold holdings and other assets to treat Covid-19 patients during that summer’s lethal delta outbreak, were not in a mood to spend even after the surge in deaths and hospitalization ebbed.

Then, as major economies began to open up and crude oil and other commodities began to get pricier, firms like Unilever responded to the squeeze by reducing how much they put in a pack. Their idea was to hold on to psychologically crucial “magic price points” — such as five or 10 rupees — in the hope that customers will replenish more often. But when inflation accelerated after the start of the war in Ukraine, there was no option except to shatter the illusion of affordability by raising prices. Volumes flat-lined in the March quarter.

“The worst of inflation is behind us,” Sanjiv Mehta, the chief executive officer, said in a statement after last week’s earnings report. That seems to be the case indeed. India’s aggregate price index rose a slower-than-expected 5.7% in December, the third straight month of cooling. That’s why perhaps instead of pushing four 100-gram bars of Lux soap for 140 rupees, Unilever is charging 156 rupees for five, according to the Business Standard. In offering an 11% price cut by bulking up pack sizes, the company is betting that most households’ budget can now accommodate an extra outlay of 16 rupees.

It’s a reasonable gamble. A bumper wheat harvest is expected this spring. Rural India, which employs two out of three workers, found jobs for a disproportionately larger share of new entrants to the labor force in November and December, according to Mahesh Vyas of CMIE, a private firm that fills in for reliable official jobs data. “Most of the additional employment is happening in rural India and not in the towns,” he says.

And that may well put the spotlight next year on faltering spending in cities. The tech industry is wobbling globally. In India, too, startups are firing employees in large numbers; some former darlings of venture capital, such as online test-prep and education firms, are becoming irrelevant now that Covid-19 restrictions on physical classes have ended.

Meanwhile, India’s software-exports industry — a large employer in metropolises — has become wary of hiring because of slowing global growth. “The pain in urban consumption seems to be showing up,” JM Financial analysts Richard Liu and others wrote last week after Asian Paints Ltd.’s earnings.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 4, 2023 at 8:22pm

-

"India is Broken" writes Princeton Economist Ashoka Modi. Says #Indians, mostly illiterate and poor, hunger for freedom and prosperity but their politicians from #Nehru to #Modi have “betrayed the economic aspirations” of millions. #BJP https://www.wsj.com/articles/india-is-broken-review-the-difficult-f... via @WSJBooks

Ashoka Mody, who was for many years a senior economist at the International Monetary Fund, is the sort of quietly efficient global technocrat who retires to a professorship at a prestigious school—in his case, Princeton. Yet he’s different from his faceless ilk of briefcase-bearers in one astonishing way: 13 years ago, an attempt was made on his life. The alleged assailant, thought to have been passed over for a job at the IMF by Mr. Mody, shot him in the jaw outside his house in Maryland.

He recovered with remarkable verve, his intellectual drive intact. Yet a mood of gloom and pessimism is unmistakable in “India Is Broken.” Today, 75 years after independence from Britain, Mr. Mody believes that India’s democracy and economy are in a state of profound malfunction. The book’s tale, he writes, “is one of continuous erosion of social norms and decay of political accountability.” You might add that it is also a tale of an audacious political experiment on the brink of failure.

India started its post-independence journey, says Mr. Mody, as “an improbable democracy” whose citizens, mostly illiterate and poor, hungered for freedom and prosperity. Generations of Indian politicians—from Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister, to Narendra Modi, the present one—have “betrayed the economic aspirations” of millions. India’s democracy no longer protects fundamental rights and freedoms in a nation over which “a blanket of violence” has fallen. A belief in “equality, tolerance and shared progress” has disappeared. And the country’s collapse isn’t just political and economic; it’s also moral and spiritual.

------------

A notable weakness in Mr. Mody’s analysis is his denial that the economic policies of Nehru and his successors were socialist. He writes of Nehru’s “alleged socialist legacy” and adds that it is a “mistake to identify central planning or big government as socialism.” Socialism, he insists, “means the creation of equal opportunity for all,” which India’s policy makers weren’t doing. Ergo, India wasn’t socialist.

If these protestations are almost laughable, Mr. Mody’s solution also invites some derision. Hope for India, he says, lies in making it a “true democracy.” And how can that be done? “We must move to an equilibrium in which everyone expects others to be honest.” This “honest equilibrium,” he says, will promote enough trust for Indians to work together “in the long-haul tasks of creating public goods and advancing sustainable development” and awakening “civic consciousness.” Mr. Mody, it is clear, has a dream. It is naïve, and it is corny. India, alas, will continue to be “broken” for many years to come.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 6, 2025 at 10:00am

-

Surbhi Kesar

@SurbhiKesar

India is not the 4th most equal country in the world.

We re-did correct & comparable calculations:

India ranks 176 (& not 4) out of 216 on income inequality.

On calorie consumption inequality, it ranks 102 out of 185.

I explain this in

@thewire_in

https://thewire.in/economy/india-inequality-pib-fact-check

https://x.com/SurbhiKesar/status/1941853786726666448

Surbhi Kesar

@SurbhiKesar

What’s the correct number?

India’s income Gini (from World Inequality Database & also the World Bank report) is 61.

That's extremely high & places India among unequal countries-ranking 176 out of 216. This rank was 115 in 2019, a rising inequality.

h/t

@ihsaanbassier

--------------

Surbhi Kesar

@SurbhiKesar

The PBI release compares India’s CONSUMPTION gini with the equal countries’ INCOME gini. Consumption inequality is usually lower than income, since rich save large parts of their income.

The wealth Gini for India is even higher - at 75 (income gini is 61).

---------

Surbhi Kesar

@SurbhiKesar

For consumption, direct comparisons can’t be made between 2011 & 23 survey.

Looking at inequality in calorie intake, which reflects disparities in food consumption:

India ranked 102 out of 185 countries in 2019 (FAO, Our World in Data). In 2009, it ranked 82.

----------

Surbhi Kesar

@SurbhiKesar

Whichever way one looks at the data, the picture is clear: India is a highly unequal country, and inequality is worsening.

Piece again

@thewire_in

https://m.thewire.in/article/economy/india-inequality-pib-fact-check

@the_hindu

@IndianExpress

@timesofindia

@bsindia

need to withdraw the story.

Earlier post pointing error:

Surbhi Kesar

@SurbhiKesar

Irresponsible reporting from

@the_hindu

@IndianExpress

@bsindia

& others about Indian being 4th equal country.

They compare India’s CONSUMPTION inequality Gini of 25.5 with INCOME inequality of other equal countries.

INCOME inequality of India is 62!

Thread explaining:

https://x.com/SurbhiKesar/status/1941755691686899993

Comment

- ‹ Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- Next ›

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

EU-India Trade Deal: "Uncapped" Mass Migration of Indians?

The European Union (EU) and India have recently agreed to a trade deal which includes an MOU to allow “an uncapped mobility for Indian students”, according to officials, allowing Indians greater ease to travel, study and work across EU states. India's largest and most valuable export to the world is its people who last year sent $135 billion in remittances to their home country. Going by the numbers, the Indian economy is a tiny fraction of the European Union economy. Indians make up 17.8%…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on January 28, 2026 at 11:00am — 8 Comments

Independent Economists Expose Modi's Fake GDP

Ruling politicians in New Delhi continue to hype their country's economic growth even as the Indian currency hits new lows against the US dollar, corporate profits fall, electrical power demand slows, domestic savings and investment rates decline and foreign capital flees Indian markets. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has questioned India's GDP and independent economists…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on January 25, 2026 at 4:30pm — 10 Comments

© 2026 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network