PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

Industrial Revolution Changed Economic, Political and Military History of the World

A research letter written by Michael Cembalest, chairman of market and investment strategy at JP Morgan, and published in the Atlantic Magazine shows how dramatic this economic power shift has been. The size of a nation's GDP depended on the size of its population and labor force in agrarian economies prior to the Industrial era. With the advent of the Industrial revolution, the use of machines relying on energy from fossil fuels dramatically enhanced labor productivity in the West and shifted the balance of power from Asia to America and Europe.

The shift in power was not just in economic terms. Enabled by machines such as steamboats and weapons like the repeating gun, the West engaged in long distance trade and warfare that led to the colonization and exploitation of Asia and Africa. The new colonies were used as a source of cheap raw materials for European factories and the colonized people served as captive customers for their manufactured products.

|

| History of Per Capita GDP of Selected Countries. Source: Angus Maddison |

While development of Asian and African nations stagnated and their share of world GDP dropped precipitously, their colonial rulers in the West prospered. Social indicators like literacy and life expectancy showed little improvement in the colonies, according to data compiled by Professor Hans Rosling. For example, his Gapminder.org animations show that life expectancy in India and Pakistan was just 32 years in 1947. In Pakistan, it has

jumped to 67 years in 2011, and per Capita

inflation-adjusted PPP income has risen from $766 in 1948 to about $3000 in 2011. Similarly, literacy rate in undivided India was just 12% in 1947. It has increased to about 67% in India and 62% in Pakistan for people 15 years and above.

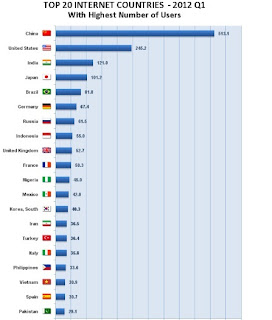

Indicators such as per capita energy consumption and Internet usage confirm the rise of Asia, particularly Asian giant China's. China's per capita energy consumption now stands at 68 million BTUs, about a fifth of US per capita energy consumption, but it's rising rapidly. Pakistan is at 15 million BTUs per capita, Bangladesh at 6 million BTUs and Sri Lanka at 10 million BTUs.In terms of Internet access, China now tops the world with over 500 million users, more than twice the number of Internet users in the United States. Among the world's top 20 are South Asian nations of India with 120 million Internet users and Pakistan with 30 million users, according to Internet World Stats.

While there has been progress on economic and social fronts in South

Asia, the combined GDP of SAARC nation is still accounts for less than

4% of the world GDP. China has significantly increased its share and now

accounts for more than 10% of the world GDP marking the biggest

economic shift since the Industrial Revolution. China's growing economic clout will ultimately translate into political and military power in the international arena.

All indications are that the pendulum of power has just begun its swing eastward in the last decade. It could be a century or more before the effects of this swing are truly felt in terms of the exercise of economic, military and political power on the world stage. Meanwhile, the 21st century is shaping up to be another American century in which United States' extraordinary power will not go entirely unchallenged by multiple potential adversaries, including China.

Here's a video discussion on the subject:

http://vimeo.com/117657383

Vision 2047: Political Revolutions and South Asia from WBT TV on Vimeo.

Here's a video of a BBC documentary about Al Andalusia or Muslim Spain:

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

Pakistan Military Industrial Revolution

China's Checkbook Diplomacy

Education Attainment in South Asia

Pakistan Needs Comprehensive Energy Policy

Social Media Growth in Pakistan

Is America Young and Barbaric?

Godfather Metaphor for Uncle Sam

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 13, 2013 at 8:05am

-

Atheist Richard Dawkins has recently disparaged Muslims by pointing out that the entire Muslim world has had fewer Nobels (10) than Cambridge's Trinity College (34). While Dawkins is correct in that assertion, it;s important to recognize that the history of humanity is not just 100 years old. It did not begin with the launch of Nobels in 1901. It stretches much further back. The defining work of Muslims in earlier centuries included development of decimal number system (still called Arabic numerals), Algebra, the idea of algorithms, first camera, fountain pen, etc. In "Lost Discoveries" by Dick Teresi, the author says, "Clearly, the Arabs served as a conduit, but the math laid on the doorstep of Renaissance Europe cannot be attributed solely to ancient Greece. It incorporates the accomplishments of Sumer, Babylonia, Egypt, India, China and the far reaches of the Medieval Islamic world." Teresi by his description of the work done by Copernicus. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, a Persian Muslim astronomer and mathematician, developed at least one of Copernicus's theorems, now called The Tusi Couple, three hundred years before Copernicus. Copernicus used the theorem without offering any proof or giving credit to al-Tusi. This was pointed out by Kepler, who looked at Copernicus's work before he developed his own elliptical orbits idea.

A second theorem found in Copernican system, called Urdi lemma, was developed by another Muslim scientist Mu'ayyad al-Din al-Urdi, in 1250. Again, Copernicus neither offered proof nor gave credit to al-Urdi. Columbia University's George Saliba believes Copernicus didn't credit him because Muslims were not popular in 16th century Europe, not unlike the situation today. http://www.riazhaq.com/2009/06/obama-islam-and-science.html

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 28, 2013 at 10:56pm

-

Combined PPP GDP of poor developing countries exceeds combined GDP of rich industrialized countries, according to a report in Huffington Post:

For the first time ever, the combined gross domestic product of emerging and developing markets, adjusted for purchasing price parity, has eclipsed the combined measure of advanced economies. Purchasing price parity—or PPP for short—adjusts for the relative cost of comparable goods in different economic markets.

According to the International Monetary Fund—the supplier of this data—emerging and developing economies will have a purchasing price parity-adjusted GDP of $42.8 trillion in 2013, while that of emerging economies will be $44.4 trillion. In other words, emerging markets will create $1.6 trillion more value in goods and services than advanced markets this year.

Advanced economies are, according to the IMF, the 34 nations that result from combining the members of the G7, euro area countries, and the 4 “newly industrialized Asian economies”—Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and South Korea. The world’s 150 other nations are considered emerging or developing.

Excluding the largest advanced economy, the United Sates, and the largest emerging economy, China, which both account from more than 30% of their respective group’s total GDP, the data show that the PPP-adjusted GDP of poorer nations surpassed that of richer ones in 2009.

It’s worth keeping in mind that the emerging economies have strength in numbers. Not only are there more emerging and developing nations; those nations also boast a larger combined population.

As such, emerging and developing economies trail far behind advanced economies in per-capita terms. Their aggregate per-capita PPP-adjusted GDP is $7,415, while the same measure for advanced nations totals $41,369.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/08/28/gdp-poor-countries_n_38303...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on September 8, 2013 at 10:00am

-

Here's NY Times Nobel Laureate economist-columnist on Ibn Khaldun's lessons for Microsoft and other established powers:

The trouble for Microsoft came with the rise of new devices whose importance it famously failed to grasp. “There’s no chance,” declared Mr. Ballmer in 2007, “that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share.”

How could Microsoft have been so blind? Here’s where Ibn Khaldun comes in. He was a 14th-century Islamic philosopher who basically invented what we would now call the social sciences. And one insight he had, based on the history of his native North Africa, was that there was a rhythm to the rise and fall of dynasties.

Desert tribesmen, he argued, always have more courage and social cohesion than settled, civilized folk, so every once in a while they will sweep in and conquer lands whose rulers have become corrupt and complacent. They create a new dynasty — and, over time, become corrupt and complacent themselves, ready to be overrun by a new set of barbarians.

I don’t think it’s much of a stretch to apply this story to Microsoft, a company that did so well with its operating-system monopoly that it lost focus, while Apple — still wandering in the wilderness after all those years — was alert to new opportunities. And so the barbarians swept in from the desert.

Sometimes, by the way, barbarians are invited in by a domestic faction seeking a shake-up. This may be what’s happening at Yahoo: Marissa Mayer doesn’t look much like a fierce Bedouin chieftain, but she’s arguably filling the same functional role.

Anyway, the funny thing is that Apple’s position in mobile devices now bears a strong resemblance to Microsoft’s former position in operating systems. True, Apple produces high-quality products. But they are, by most accounts, little if any better than those of rivals, while selling at premium prices.

So why do people buy them? Network externalities: lots of other people use iWhatevers, there are more apps for iOS than for other systems, so Apple becomes the safe and easy choice. Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.

Is there a policy moral here? Let me make at least a negative case: Even though Microsoft did not, in fact, end up taking over the world, those antitrust concerns weren’t misplaced. Microsoft was a monopolist, it did extract a lot of monopoly rents, and it did inhibit innovation. Creative destruction means that monopolies aren’t forever, but it doesn’t mean that they’re harmless while they last. This was true for Microsoft yesterday; it may be true for Apple, or Google, or someone not yet on our radar, tomorrow.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/26/opinion/krugman-the-decline-of-e-...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on October 19, 2013 at 5:04pm

-

Why is the English laguage so dominant and widely used today? It's because language does not exist or grow in vacuum. As a means of communication, it reflects the state of the people whose language it is. The global ascendance of the English language has coincided with the rise of the Anglo-Saxon people beginning with the Industrial Revolution in 18th century England. It marked a dramatic shift of global power from East to West.

http://www.riazhaq.com/2012/07/global-power-shift-since-industrial....

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on October 30, 2013 at 9:38pm

-

Here's an excerpt of The Economist magazine story on productivity gap between US and developing nations:

The productivity gap, an indicator of a country’s output capabilities, is the ratio between the productivity of a benchmark country (such as the United States) and that of a less developed economy. The latest Latin America Outlook from the OECD, a think-tank, compared the productivity gaps of selected countries in the region with those of economies in Asia. In general, productivity gaps in Asian countries have narrowed significantly over the past three decades. America’s productivity in 1980 was 125 times that of China; by 2011 the gulf had come down to 17 times. In Latin America and the Caribbean, however, not only was there a much smaller reduction, in many cases the gap had grown.

http://www.economist.com/news/economic-and-financial-indicators/215...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on February 25, 2014 at 8:09pm

-

One can probably get a good historic overview of India's economic and social indicators data by reading British economist Angus Maddison and Swedish statistician Hans Rosling.

Maddison estimates that in PPP terms in 1990 dollars. In 1 AD, India’s GDP per capita was $450, as was China’s. But Italy under the Roman Empire had a per capita income of $809. In 1000 AD, India’s per capita income was $450 and China’s $466. But the average of the West Asian countries, such as Turkey and Iraq, was much higher at $621. In terms of general prosperity, therefore, it was the Arab world that was doing well a millennium ago. The Caliphate in Baghdad was a centre of power at the time and both science and culture flourished.

http://www.livemint.com/Opinion/Nb7KkZ3yOVSNW3vHf9K1oM/World-histor...

Rosling (www.gapminder.org) has estimated India's life expectancy in 1800 at about 23 years, lower than its peers at the time.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 8, 2017 at 2:01pm

-

Apologists for empire like to claim that the British brought democracy, the rule of law and trains to India. Isn’t it a bit rich to oppress, torture and imprison a people for 200 years, then take credit for benefits that were entirely accidental?

by Shashi Tharoor

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/08/india-britain-empire-...

Many modern apologists for British colonial rule in India no longer contest the basic facts of imperial exploitation and plunder, rapacity and loot, which are too deeply documented to be challengeable. Instead they offer a counter-argument: granted, the British took what they could for 200 years, but didn’t they also leave behind a great deal of lasting benefit? In particular, political unity and democracy, the rule of law, railways, English education, even tea and cricket?

Indeed, the British like to point out that the very idea of “India” as one entity (now three, but one during the British Raj), instead of multiple warring principalities and statelets, is the incontestable contribution of British imperial rule.

Unfortunately for this argument, throughout the history of the subcontinent, there has existed an impulsion for unity. The idea of India is as old as the Vedas, the earliest Hindu scriptures, which describe “Bharatvarsha” as the land between the Himalayas and the seas. If this “sacred geography” is essentially a Hindu idea, Maulana Azad has written of how Indian Muslims, whether Pathans from the north-west or Tamils from the south, were all seen by Arabs as “Hindis”, hailing from a recognisable civilisational space. Numerous Indian rulers had sought to unite the territory, with the Mauryas (three centuries before Christ) and the Mughals coming the closest by ruling almost 90% of the subcontinent. Had the British not completed the job, there is little doubt that some Indian ruler, emulating his forerunners, would have done so.

Far from crediting Britain for India’s unity and enduring parliamentary democracy, the facts point clearly to policies that undermined it – the dismantling of existing political institutions, the fomenting of communal division and systematic political discrimination with a view to maintaining British domination.

In the years after 1757, the British astutely fomented cleavages among the Indian princes, and steadily consolidated their dominion through a policy of divide and rule. Later, in 1857, the sight of Hindu and Muslim soldiers rebelling together, willing to pledge joint allegiance to the enfeebled Mughal monarch, alarmed the British, who concluded that pitting the two groups against one another was the most effective way to ensure the unchallenged continuance of empire. As early as 1859, the then British governor of Bombay, Lord Elphinstone, advised London that “Divide et impera was the old Roman maxim, and it should be ours”.

Since the British came from a hierarchical society with an entrenched class system, they instinctively looked for a similar one in India. The effort to understand ethnic, religious, sectarian and caste differences among Britain’s subjects inevitably became an exercise in defining, dividing and perpetuating these differences. Thus colonial administrators regularly wrote reports and conducted censuses that classified Indians in ever-more bewilderingly narrow terms, based on their language, religion, sect, caste, sub-caste, ethnicity and skin colour. Not only were ideas of community reified, but also entire new communities were created by people who had not consciously thought of themselves as particularly different from others around them.

Large-scale conflicts between Hindus and Muslims (religiously defined), only began under colonial rule; many other kinds of social strife were labelled as religious due to the colonists’ orientalist assumption that religion was the fundamental division in Indian society.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on April 21, 2017 at 10:04am

-

#India's #Nobel Laureate Rabindranath #Tagore became the embodiment of how the west wanted to see the east.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/may/07/rabindranath-...

The success turned everyone's heads, including Tagore's. He became the most prominent embodiment of how the west wanted to see the east – sagelike, mystical, descending from some less developed but perhaps more innocent civilisation; above all, exotic. He looked the part, with his white robes and flowing beard and hair, and sometimes overplayed it. Of course, the truth was more complicated. The Tagores were among Kolkata's most influential families. They'd prospered in their role as middle men to the East India Company, whose servants named them Tagore because it was more easily pronounced than the Bengali title, Thakur. The west wasn't strange to them. Rabindranath's grandfather, Dwarkanath, owned steam tug companies and coal mines, became a favourite of Queen Victoria's and died in England (his tombstone is in Kensal Green cemetery). As for the poet himself, this was his third visit to London. On his first, he'd heard the music hall songs and folk tunes that he later incorporated into his distinctive musical genre, rabindra sangeet.

More than anything, what Tagore stood for was a synthesis of east and west. He admired the European intellect and felt betrayed when Britain's conduct in India let down the ideal. His western enthusiasts, however, saw what they wanted to see. First, he was an exotic fashion and then he was not. "Damn Tagore," wrote Yeats in 1935, blaming the "sentimental rubbish" of his later books for ruining his reputation. "An Indian has written to ask what I think of Rabindrum [sic] Tagore," wrote Philip Larkin to his friend Robert Conquest in 1956. "Feel like sending him a telegram: 'Fuck all. Larkin.'"

Is his poetry any good? The answer for anyone who can't read Bengali must be: don't know. No translation (according to Bengalis) lives up to the job, and at their worst, they can read like In Memoriam notices: "Faith is the bird that feels the light when the dawn is still dark" is among the better lines. Translator William Radice thinks that Tagore's willingness to tackle the big questions, heart on sleeve, has made him vulnerable to "philistinism or contempt". That may be so – see Larkin – but perhaps the time has come for us to forget Tagore was ever a poet, and think of his more intelligible achievements. These are many. He was a fine essayist; an educationist who founded a university; an opponent of the terrorism that then plagued Bengal; a secularist amid religious divisions; an agricultural improver and ecologist; a critical nationalist. In his fiction, he showed an understanding of women – their discontents and dilemmas in a patriarchal society – that was ahead of its time. On his 150th anniversary, we shouldn't resist two cheers, at least.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on February 8, 2018 at 7:29am

-

Height, lifespan, GDP: Humanity has stagnated for most of its history

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/02/height-lifespan-gdp-humanity...Measuring economic growth is difficult, especially for periods for which little information is available. However, harmonized national accounts were set up in most countries after World War II, and they provide different ways to measure aggregate production, either through summing the added values of all resident production sectors, or through summing all the incomes distributed by those sectors. Based on a broad set of historical studies, Maddison (2003)reconstructed income per capita data over the past two centuries, and added some point estimates for earlier periods (in 1 Common Era (CE), 1000 CE, 1500 CE, 1600 CE and 1700 CE). Such estimates often require educated guesses on unobservable trends, but they nonetheless show the best information given what is known at one point in time.

Recently, Bolt and van Zanden, (2013) have revised and complemented Maddison’s work with the “Maddison project”), and some of the findings are striking.

Over the past millennium, income per capita in the selected countries has increased 32-fold, from 717 US dollars per person per year around the year 1000 to 23,086 dollars in 2010. This contrasts sharply with the previous millennia, when there was almost no advance in income per capita. The figure shows that it started rising and accelerating around the year 1820 and it has sustained a steady rate of increase over the last two centuries. One of the main challenges for growth theory is to understand this transition from stagnation to growth and in particular to identify the main factor(s) that triggered the take-off.

Is the finding that there was stagnation in the standard of living until 1820 truly robust? This claim is particularly important given that mankind experienced significant technological improvements that would have been expected to increase productivity and income per person, from the Neolithic revolution to the invention of the printing press.

Two facts corroborate the idea that there was indeed stagnation over the most part of human history: first, estimates of longevity computed on specific groups across time and space do not display any trend before 1700 CE. For example, De la Croix and Licandro (2015) show using a long-running database of 300,000 famous people that there was no trend in mortality during most of human history, confirming the existence of a Malthusian stagnation epoch.

Have you read?

Second, body height computed from skeletal remains does not display any trend either, while height is known to depend very much on nutrition when young (Koepke and Baten, 2005). This indicates that there was no systematic improvement in nutrition over time. One has to wait until the 19th century to observe a trend in height, as witnessed by the data of the Swedish army.

The three measures of standard of living proposed here – GDP per capita, height and lifespan – are therefore in the same direction: that of stagnation for most of human history. The economic growth that we now enjoy, with its positive effects on the standard of living but also its negative effects on the environment, is therefore an unprecedented and recent phenomenon on a historical scale.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 25, 2020 at 7:45am

-

EU Foreign Policy Chief Josep Borrell: “Analysts have long talked about the end of an American-led system and the arrival of an Asian century....This is now happening in front of our eyes” #US #China #Europe #America #Asia #COVIDー19 #Coronavirus https://www.newsweek.com/pressure-choose-sides-us-china-eu-diplomat...

Pressure to choose sides between the U.S. and China is growing amid the arrival of an "Asian century," a top European diplomat said today.

Europe is facing an "existential crisis" sparked by the COVID-19 crisis, which could be a catalyst in the demise of an American-led system, according to Josep Borrell, a vice president of the European Commission branch of the European Union (EU).

The diplomat, who also serves as the EU's High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, told virtual participants of the German Ambassadors' Conference 2020 that the pandemic could be considered a "great accelerator of history."

Borrell claimed that in the world that emerges Asia will be increasingly important, while noting that China is fast becoming "more powerful and assertive."

Ads by scrollerads.com

"Analysts have long talked about the end of an American-led system and the arrival of an Asian century. This is now happening in front of our eyes," he said. "If the 21st century turns out to be an Asian century, as the 20th was an American one, the pandemic may well be remembered as the turning point of this process."

His comments were first reported by the Associated Press.

Tensions have spiked between the U.S. and China in recent years,, with tit-for-tat trade tariffs being slapped on goods by both countries. U.S. officials have also complained about national security concerns linked to Chinese tech firms, and 5G.

This month, president Donald Trump told Fox Business that he didn't want to speak with China's leader, Xi Jinping, and suggested the U.S. may cut ties.

"We could cut off the whole relationship," he told Fox host Maria Bartiromo. "Now if you did, what would happen? You would save 500 billion dollars."

In April, Trump said in a briefing that "serious investigations" were being conducted into China's handling of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which ravaged America this year, causing more than 1.6 million infections and close to 98,000 deaths.

China has claimed its own virus infection and death rates have plunged, although official health statistics have been met with widespread scepticism.

"We are not happy with that whole situation because we believe it could have been stopped at the source, it could have been stopped quickly, and it wouldn't have spread all over the world. And we think that should have happened," Trump fumed.

Borrell said today that the need for multilateral cooperation has "never been greater" but raised concerns that leadership from the White House is lacking.

"This is the first major crisis in decades where the U.S. is not leading the international response," the EU diplomat said. "Maybe they don't care, but everywhere we look we see increasing rivalries, especially between the U.S. and China.

He added: "The pressure to choose sides is growing. As the EU, we should follow our own interests and values and avoid being instrumentalized by one or the other.

Borrell went on to say that U.S.-China rivalry is often having a "paralysing" effect on the multilateral system, fueling more arguments and vetoes than agreements.

According to the transcript, he said: "We need a more robust strategy for China, which also requires better relations with the rest of democratic Asia. That's why we must invest more in working with India, Japan, South Korea et cetera.

Comment

- ‹ Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- Next ›

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

EU-India Trade Deal: "Uncapped" Mass Migration of Indians?

The European Union (EU) and India have recently agreed to a trade deal which includes an MOU to allow “an uncapped mobility for Indian students”, according to officials, allowing Indians greater ease to travel, study and work across EU states. India's largest and most valuable export to the world is its people who last year sent $135 billion in remittances to their home country. Going by the numbers, the Indian economy is a tiny fraction of the European Union economy. Indians make up 17.8%…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on January 28, 2026 at 11:00am — 8 Comments

Independent Economists Expose Modi's Fake GDP

Ruling politicians in New Delhi continue to hype their country's economic growth even as the Indian currency hits new lows against the US dollar, corporate profits fall, electrical power demand slows, domestic savings and investment rates decline and foreign capital flees Indian markets. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has questioned India's GDP and independent economists…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on January 25, 2026 at 4:30pm — 10 Comments

© 2026 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network