PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

Powerful Oligarchs of South Asia

Like India, Pakistan is an oligarchy as well. But it is dominated by the feudal rather than the industrial elite. These oligarchs dominate Pakistan's legislature. Vast majority of them come from rural landowning and tribal backgrounds. Well-known names include the Bhuttos and Khuhros of Larkana, the Chaudhrys of Gujarat, Tiwanas of Sargodha, Daulatanas of Vehari, the Jatois and Qazi Fazlullah family of Sindh, the Gilanis, Qureshis and Gardezis of Multan, the Nawabs of Qasur, the Mamdots of Ferozpur/Lahore, Ghaffar Khan-Wali Khan family of Charsadda and various Baloch tribal chieftains like Bugtis, Jamalis, Legharis, and Mengals. The power of these political families is based on their heredity, ownership of vast tracts of land and a monopoly over violence – the ability to control, resist and inflict violence.

Pakistan, too, has an industrial elite. Its biggest names include Manshas (Nishat Group), Syed Maratib Ali and Babar Ali (Packages) Saigols, Hashwanis, Adamjees, Dawoods, Dadabhoys, Habibs, Monnoos, Lakhanis and others. But their collective power pales in comparison with the power of the big feudal families. The only possible exception to this rule are the Sharif brothers who own the Ittefaq Group of Industries and also lead Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz Group), one of the two largest political parties. But the Sharifs too rely on political support from several feudal families who are quick to change loyalties.

The origins of the differences between Indian and Pakistan oligarchies can be found in some of the earliest decisions by the founding fathers of the two nations. India's first prime minster dismantled the feudal system almost immediately after independence. But Nehru not only left the industrialists like Birla and Tata alone, his policies protected them from foreign competition by imposing heavy tariff barriers on imports. In Pakistan, there was no serious land reform, nor was any real protection given to domestic industries from foreign competition.

Oligarchy is the antithesis of democracy. However, it's important to understand the differences between feudal and industrial oligarchies, and their effects on nations as observed in South Asia.

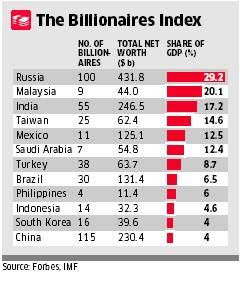

Industrial oligarchs of India have accelerated economic growth, created a large number of middle class jobs, increased India's exports significantly and paid higher taxes to the tune of 17% of GDP. This has created a trickle-down effect in terms of increased public spending on education, health care and various social programs to fight poverty. Unfortunately, the tax collection in Pakistan's feudal oligarchy remains dismally low at less than 10% of GDP, and the lack of revenue makes its extremely difficult for Pakistani state to spend more on basic human development and poverty reduction programs.

As to the future, the hope for Pakistan is that the feudal hold on power will eventually weaken as the nation sustains its rapid pace of urbanization. Pakistan has and continues to urbanize at a faster pace than India. From 1975-1995, Pakistan grew 10% from 25% to 35% urbanized, while India grew 6% from 20% to 26%. From 1995-2025, the UN forecast says Pakistan urbanizing from 35% to 60%, while India's forecast is 26% to 45%. For this year, a little over 40% of Pakistan's population lives in the cities. The political power shift from rural to urban areas may eventually produce a more industry-friendly government in the future. Such a government can be expected to help increase the tax base significantly, permitting greater spending on education and health care, and reduced dependence on foreign aid.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

India: World's Largest Oligarchy

Who Owns Pakistan?

Tax Evasion Fosters Aid Dependence

Urbanization in Pakistan Highest in South Asia

India's 2G Scandal

Bloody Revolution in India?

Is There a Threat of Oligarchy in India?

Political Patronage in Pakistan

India at Davos 2011: Story of Corruption and Governance Deficit

Challenges to Indian Democracy

India After 63 Years of Independence

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on September 20, 2011 at 11:14pm

-

India's main planning body has said half a dollar a day is "adequate" for a villager to spend on food, education and health, according to the BBC:

Critics say that the amount fixed by the Planning Commission is extremely low and aimed at "artificially" reducing the number of poor who are entitled to state benefits.

There are various estimates on the exact number of poor in India.

Officially, 37% of India's 1.21bn people live below the poverty line.

But one estimate suggests the true figure could be as high as 77%.

The Planning Commission has told India's Supreme Court that an individual income of 25 rupees (52 cents) a day would help provide for adequate "private expenditure on food, education and health" in the villages.

In the cities, it said, individual earnings of 32 rupees a day (66 cents) were adequate.

The Planning Commission was responding to a direction from the court to update its poverty line figures to reflect rising prices.

India has been struggling to contain inflation which is at a 13-month high of 9.78%.

Many experts have said the income limit to define the poor was too low.

"This extremely low estimated expenditure is aimed at artificially reducing the number of persons below the poverty line and thus reduce government expenditure on the poor," well-known social activist Aruna Roy told The Hindu newspaper.

The Planning Commission also told the court that 360 million Indians are now being supplied with subsidised food and cooking fuel through the network of state-owned shops.

A World Bank report in May said attempts by the Indian government to combat poverty were not working.

It said aid programmes were beset by corruption, bad administration and under-payments.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-south-asia-14998248

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 4, 2012 at 9:18am

-

Here are some excerpts from Raymond Baker's book "Capitalism's Achilles Heel" regarding Pakistan's venal politicians:

"While Benazir Bhutto hated the generals for executing her father, Nawaz Sharif early on figured out that they held the real power in Pakistan. His father had established a foundry in 1939 and, together with six brothers, had struggled for years only to see their business nationalized by Ali Bhutto’s regime in 1972. This sealed decades of enmity between the Bhuttos and the Sharifs. Following the military coup and General Zia’s assumption of power, the business—Ittefaq—was returned to family hands in 1980. Nawaz Sharif became a director and cultivated relations with senior military officers. This led to his appointment as finance minister of Punjab and then election as chief minister of this most populous province in 1985. During the 1980s and early 1990s, given Sharif ’s political control of Punjab and eventual prime ministership of the country, Ittefaq Industries grew from its original single foundry into 30 businesses producing steel, sugar, paper, and textiles, with combined revenues of $400 million, making it one of the biggest private conglomerates in the nation. As in many other countries, when you control the political realm, you can get anything you want in the economic realm."

-----------

Like Bhutto, offshore companies have been linked to Sharif, three in the British Virgin Islands by the names of Nescoll, Nielson, and Shamrock and another in the Channel Islands known as Chandron Jersey Pvt. Ltd. Some of these entities allegedly were used to facilitate purchase of four rather grand flats on Park Lane in London, at various times occupied by Sharif family members. Reportedly, payment transfers were made to Banque Paribas en Suisse, which then instructed Sharif ’s offshore companies Nescoll and Nielson to purchase the four luxury suites.

-----------

Upon taking office in 1988, Bhutto reportedly appointed 26,000 party hacks to state jobs, including positions in state-owned banks. An orgy of lending without proper collateral followed. Allegedly, Bhutto and Zardari “gave instructions for billions of rupees of unsecured government loans to be given to 50 large projects. The loans were sanctioned in the names of ‘front men’ but went to the ‘Bhutto-Zardari combine.’ ” Zardari suggested that such loans are “normal in the Third World to encourage industrialisation.” He used 421 million rupees (about £10 million) to acquire a major interest in three new sugar mills, all done through nominees acting on his behalf. In another deal he allegedly received a 40 million rupee kickback on a contract involving the Pakistan Steel Mill, handled by two of his cronies. Along the way Zardari acquired a succession of nicknames: Mr. 5 Percent, Mr. 10 Percent, Mr. 20 Percent, Mr. 30 Percent, and finally, in Bhutto’s second term when he was appointed “minister of investments,” Mr. 100 Percent.http://books.google.com/books?id=Wkd0--M6p_oC&printsec=frontcov...

http://books.google.com/books?id=Wkd0--M6p_oC&printsec=frontcov...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 23, 2014 at 1:49pm

-

Here's a BBC report on "paid news" in Indian elections:

In recent years, India has seen a growing phenomenon called 'paid news'. This is where money changes hands in return for sympathetic press coverage.

There have been hundreds of cases involving politicians, celebrities and businessmen paying for favourable reports in the media dressed up as real news.

With the country gearing up for elections soon, the issue has been in sharp focus, but is there any chance of tackling the problem?

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 29, 2014 at 4:41pm

-

Modi is where he is today – on the cusp of power — not because the country is becoming more communal but because the Indian corporate sector is becoming more impatient. Every opinion poll that shows him inching towards power sets off a bull run on the Bombay Stock Exchange. In a recent dispatch for the Financial Times, James Crabtree noted the exceptional gains notched up by Adani Enterprises – the company’s share price has shot up by more than 45 per cent over the past month compared to the 7 per cent rise registered by the Sensex. One reason, an equities analyst told the FT, is that investors expect a government headed by Modi to allow Adani to expand his crucial Mundra port despite the environmental complications involved. “So the market is saying that, beyond the simple proximity of Mr Adani and Mr Modi, these clearances may no longer be so hard to get under a BJP regime,” the analyst is quoted as saying.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 13, 2014 at 7:47am

-

Your (Thomas Piketty's) data says that the top 1% in India owns about 8-9 % of national income. That's not much compared to the West, yet inequalities here appear starker. Is it that inequality being a relative measure, the absolute nature of poverty gets sidelined?

Let me make it clear that there are major problems with the measurement of income inequality in India. Of course, there are data problems in every country. But among all democracies, India is probably the country for which we have met the largest difficulties in getting reliable data. In particular, India's income tax administration has almost given up compiling detailed income tax statistics, although detailed yearly reports called "All-India Income Tax Statistics" are available from 1922 to 2000. This lack of transparency is problematic, because self-reported survey data on consumption and income is not satisfactory for the top part of the distribution, and income tax data is a key additional source of information in every country. The consequence is that we know very little about the actual decomposition of GDP growth by income and social groups in India over the past few decades.

You propose a 'utopian' global wealth tax to redistribute wealth. If it is so impracticable, what's the use of proposing it?

A global wealth tax together with a global government is certainly a utopia. But there is a lot that can be achieved at the national level and through intergovernmental agreements. In particular, countries like US, China or India are sufficiently large to make their tax system more progressive. For instance, the US — about one quarter of world GDP — could transform their property tax into a progressive tax on net wealth. They are sufficiently large to impose credible sanctions on countries and banks (like Swiss banks) that do not transmit the information they need to enforce their tax law.

You criticize economists for their 'childish passion' for mathematics in your book. How should they deal with their subject?

I am trying to put the distributional question and the study of long-run trends back at the heart of economic analysis. In that sense, I am pursuing a tradition which was pioneered by the economists of the 19th century, including David Ricardo and Karl Marx. One key difference is that I have a lot more historical data. With the help of many scholars, we have been able to collect a unique set of data covering three centuries and over 20 countries. This is by far the most extensive database available in regard to the historical evolution of income and wealth. This book proposes an interpretative synthesis based upon this data. I also use simple theoretical models in order to account for the facts.

http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/stoi/deep-focus/Top-1-in-In...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 9, 2015 at 1:01pm

-

Shahid Burki Op Ed in Express Tribune:

I don’t have a great deal of confidence in the numbers the government in Pakistan puts out about the economy and the state of society. I believe that the estimates of the GDP and its recent growth don’t reflect the real picture: both the size of the economy and its rate of increase are underestimated. Since the country has not held a population census for 17 years, we are proceeding on guesswork about the size of the population, its regional distribution, the size of the urban population and the rate at which it is increasing. There are no reliable estimates of the distribution of income among different segments of the population. The claim that Pakistan has the lowest income inequality in the South Asian region is hard to accept. Sometimes, it is better to trust one’s eyes than official data. The levels of consumption one generally sees in the large cities suggest significant inequality.

Economists generally consider three forms of disparity: wealth (wealth inequality), income (income inequality), and consumption (consumption inequality). Of these, income inequality is the most frequently discussed subject. It has two important aspects: interpersonal and regional inequalities. The issue of economic inequality leads to concerns about equity, equality of outcome, and equality of opportunity.

There was considerable and an excited discussion of the causes of inequality in the West following the publication of the French economist Thomas Piketty’s book, Capitalism in the 21st Century. Institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank have also given a great deal of attention to the subject. According to a June 2015 report of the IMF, “widening income inequality is the defining challenge of our time. In advanced economies, the gap between the rich and poor is at its highest level in decades. Inequality trends have been more mixed in emerging markets and developing countries, with some countries experiencing declining inequality, but pervasive inequities in access to education, health care, and finance remain.”

The interest in the subject of equality is not only on moral grounds; as social scientists began to emphasise decades ago, perception of discrimination that leads to inequality can have diverse consequences. The economist Albert O Hirschman pointed out in his book, Exit, Voice and Loyalty published decades ago, that unfair treatment on the part of a segment of the population can lead to one of three reactions: those unhappy with their situation can choose to stay within the system hoping that corrections will be made from within; or they may raise their voice, drawing attention to their situation; or they may exit from the system altogether. We have seen examples of all three in our own history.

---------

What are the many reasons for persistent inequality in the country? In neo-classical economics, income inequality is the result of the differences in value added by labour, capital and land. Within labour income, distribution is due to differences in value added by different categories of workers. As Piketty observed on the basis of data collected and investigated from some of the more advanced countries, the return on capital is much higher than from labour. Unless the state begins to tax those who earn their incomes from the use of capital and to raise resources that would increase the productivity of the poor, inequalities will continue to increase.

http://tribune.com.pk/story/935045/technology-and-inequality/

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 12, 2015 at 9:22pm

-

French Economist-Author Thomas Piketty to #India’s "Hypocritical" "Self-Serving" Elite: ‘Learn From History’ http://nyti.ms/1lQ5b4z

After he fled to the authors’ lounge, Mr. Piketty told me that he found the elite of India “hypocritical” for urging their government to address inequality by pouring resources into economic development, like building infrastructure or helping selected industries. This is self-serving, he says, and only increases the gap between the rich and the poor. In his opinion, governments should find the means to invest more in social welfare, like primary education and health care.

Before the world wars, he said, “the French elite used to say the same things that the Indian elite now say, that inequality would be reduced with rising development.” But after the wars, he said, the French began to see that direct investment in welfare was the way forward.

“I hope the Indian elite learn from the stupid mistakes of the other elites,” he said. “Learn from history.”

India is just emerging from what many regard as a catastrophic experiment in a type of socialism, the sort that economists like Amartya Sen, the Nobel laureate, say was not socialism in the first place, because it neglected health care and primary education. What the Indian elite learned from that history was to fear and loathe the idea of the welfare state.

In 1991, India reached the nadir of an economic crisis that forced it, in exchange for a financial rescue from the International Monetary Fund, to begin liberalizing its economy along the free market lines that were championed then by Washington. In the years that followed, the rich and the educated benefited the most, though the poor are better off today than they were before those changes.

Having prospered in recent decades, the Indian elite have faith in this economic model. But there is also a wide acceptance that India’s inadequate investments in education and health are holding the nation back.

“The problems India is trying to solve are problems other countries are trying to solve,” Mr. Piketty had said during his lecture. “India is trying to solve very complicated problems.”

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on July 27, 2016 at 9:40am

-

#Modi's #India, world's biggest oligarchy, sends elite commandos to guard billionaire's wife http://www.riazhaq.com/2011/07/india-worlds-biggest-oligarchy.html …

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2016/07/27/india-...

Imagine, if you will, the kind of outcry that would occur in the United States if the government sent a Secret Service detail to protect Melinda Gates, wife of Bill Gates.

That explains a bit of the furor in India this week after a Hindustan Times report that the Indian government was dispatching a team of elite commandos to protect Nita Ambani, the socialite wife of India’s richest man.

Her husband, Mukesh Ambani, an oil and gas magnate worth $21 billion, has had a government security escort since 2013, when he was the subject of terror threats, and covers the costs himself.

But in a country where there is a shortage of police officers, the news about 10 additional officers for the wife rankled.

“Women raped daily in Delhi. No security for them despite repeated requests. But [prime minister Narendra Modi] providing security to his friends,” Delhi’s chief minister, Arvind Kejriwal, said in a tweet.

The government said that a threat-assessment report by central security agencies deemed Nita Ambani’s protection necessary, according to the Hindustan Times report.

Ambani, 52, is an art collector and serves on the board of directors of her husband's company and chair of its charity wing. The couple live in a famous 27-story home in Mumbai that has a ballroom, a movie theater and six parking levels and has been featured in Vanity Fair.

As pretentious as it gets - 27 floor Mumbai house of Ambani family, 600 servants, $2 billion. pic.twitter.com/XsQUwk3mm6

— Frank Vivier (@dievlamgat) June 17, 2016

The news reignited the debate of “VIP privilege” in India, where in recent years ordinary citizens have begun to chafe against what they see as undue perks given to the rich and famous, who are whisked through airport waiting lines, ride in motorcades that clog traffic and, in the case of politicians, live in luxury, government-assigned bungalows.

The data site IndiaSpend estimated in 2013 that in India, which is short about a half-million police officers, an estimated 47,000 officers are dispatched to protect 14,842 VIPs.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on May 13, 2018 at 4:57pm

-

https://twitter.com/FaseehMangi/status/994667028664471552

According to the infographic (tweeted by Faseeh Mangi) , at the top of the group is the IGI Group, which includes IGI insurance, IGI Life, Nestle. Tri-Pack Films, and Sanofi-Aventis with a combined total market cap of Rs677 billion which makes up 7.4 per cent of KSE.

Coming in second is the Hussain Dawood Group which includes companies such as Engro Corp, Engro Foods, Engro Fertilisers, Engro Polymer, Engro PowerGen, Dawood Hercules, and Dawood Lawrencepur with a total combined market cap at Rs442 billion and 4.8 per cent of KSE.

Fauji Foundation is ranked in the third spot with companies such as Fauji Fertilizer, Fauji Foods, Fauji Fertilizer Bin Qasim, Fauji Cement, Askari Bank, and Mari Petroleum. The Fauji Foundation Group, according to the report, has a total market capitalisation of Rs432 billion, and a a total KSE share of 4.6 per cent.

Mian Mansha’s Mansha Group follows with a total market capitalisation at Rs408 billion, and 4.4 per cent share of KSE. Mansha Group includes names such as Nishat Mills, MCB Bank, DG Khan Cement, Adamjee Insurance, Nishat Chunian, Lalpir Power, and Nishat Power.

At number 5 in terms of market capitalization is the Habib Group which includes companies such as the Indus Motor Company, Thal Limited, Habib Insurance, Habib Sugar Mills, Bank Al-Habib, Habib Metro, and Shabbir Tiles. Total market capitalisation for the group stands at Rs326 billion and its total share in the stock exchange is at 3.6 per cent.

Bestway Group, which includes United Bank Limited (UBL) and Bestway Cement come in next with a market capitalization of Rs310 billion and a 3.4 per cent share of KSE.

Tabba Group, at number 7 boasts of a total market capitalisation of Rs298 billion and KSE percentage share of 3.3 per cent. The group includes companies such as Lucky Cement, ICI Pakistan, and Gadoon Textiles.

With a total market capitalisation of Rs143 billion, the Atlas Group which includes companies such as Honda Atlas Cars, Atlas Honda, Atlas Battery, and Atlas Insurance, has a 1.6 per cent share in KSE.

Chinoy Group, Saigol Group, and JS Group come in last in the list of the 11 groups which own 35 per cent of market capitalisation of Pakistan’s Stock Exchange with total market caps at Rs90 billion, Rs79 billion, and Rs43 billion respectively, and a respective percentage share of 1 percent, 0.9 per cent, and 0.5 percent. The Chinoy Group includes Pakistan Cables, International Industries, and International Steel. The Saigol Group includes companies such as Pak-Elektron, Maple Leaf Cement, and Kohinoor Textile Mills. JS Group includes Jahangir Siddique Company, JS Bank, BankIslami, JS Investments, and JS Global.

https://profit.pakistantoday.com.pk/2018/05/14/who-owns-pakistan-11...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 9, 2022 at 2:39pm

-

How political will often favors a coal billionaire and his dirty fossil fuel

The tale of Gautam Adani’s giant power plant reveals how political will in India bends in favor of the dirty fuel

By Gerry Shih, Niha Masih and Anant Gupta

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/12/09/india-coal-gautam-a...

GODDA, India — For years, nothing could stop the massive coal-fired power plant from rising over paddies and palm groves here in eastern India.

Not objections from local farmers, environmental impact review boards, even state officials. Not pledges by India’s leaders to shift toward renewable energy.

Not the fact that the project, ultimately, will benefit few Indians. When the plant comes online, now scheduled for next week, all of the electricity it generates is due to be sold at a premium to neighboring Bangladesh, a heavily indebted country that has excess power capacity and doesn’t need more, documents show.

The project, however, will benefit its builder, Gautam Adani, an Indian billionaire who according to Global Energy Monitor is the largest private developer of coal power plants and coal mines in the world. When his companies’ stock peaked in September, the Bloomberg Billionaires Index ranked Adani as the second-richest person on the planet, behind Elon Musk.

--------

One of the power projects would be built by Adani, who had provided a corporate jet for Modi to use during his political campaign and accompanied the newly elected prime minister on his first visits to Canada and France. After Modi’s trip to Bangladesh, that country’s power authority contracted with Adani to build a $1.7 billion, 1,600-megawatt coal power plant. It would be situated 60 miles from the border, in a village in Godda district.

At the time, the project was seen as a win-win.

For Modi, it was an opportunity to bolster his “Neighborhood First” foreign policy and promote Indian business. Modi asked Bangladesh’s prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, to “facilitate the entry of Indian companies in the power generation, transmission and distribution sector of Bangladesh,” according to an Indian Foreign Ministry readout of their meeting.

For her part, Hasina envisioned lifting her country into middle-income status by 2020. Electricity demand from Bangladesh’s humming garment factories and booming cities would triple by 2030, the government estimated.

-----------

Facing a looming power glut, Bangladesh in 2021 canceled 10 out of 18 planned coal power projects. Mohammad Hossain, a senior power official, told reporters that there was “concern globally” about coal and that renewables were cheaper.

But Adani’s project will proceed. B.D. Rahmatullah, a former director general of Bangladesh’s power regulator, who also reviewed the Adani contract, said Hasina cannot afford to anger India, even if the deal appears unfavorable.

“She knows what is bad and what is good,” he said. “But she knows, ‘If I satisfy Adani, Modi will be happy.’ Bangladesh now is not even a state of India. It is below that.”

A spokesman for Hasina and senior Bangladeshi energy officials did not respond to a detailed list of questions and repeated requests seeking comment.

Comment

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Trump Leads America into an Unpopular War in the Middle East!

President Donald Trump joined Israel in yet another war of choice in the Middle East last week. Polls conducted in the United States immediately after the start of the Iran war show that the majority of Americans do not support it. A YouGov snap poll fielded Saturday — the day of the strikes — found 34% of Americans approve of the U.S. attacks on Iran, with 44%…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on March 3, 2026 at 10:00am — 3 Comments

India-Israel Axis Threatens Peace in South Asia

The bonhomie between Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu, an indicted war criminal, and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, accused of killing thousands of Muslims, was on full display this week in Israel. Both leaders committed to supporting the Afghan Taliban regime which is accused of facilitating cross-border terrorist attacks by the TTP in Pakistan. Mr. Modi was warmly welcomed by…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on February 27, 2026 at 10:45am — 2 Comments

© 2026 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network