PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network

The Global Social Network

Was Musharraf's Rule Legitimate?

F

Former President Musharraf's detractors argue that he lacked legitimacy because he came to power through a coup which removed a duly elected government in 1999.

Implicit in Musharraf's opponents' argument is the assumption that the electoral process is the only source of legitimacy for a ruler. It ignores the possibility that the will of the people can also be expressed in ways other than elections to confer legitimacy on a leader. It rejects the notion that a leader can earn legitimacy in the eyes of the people by delivering results to the people through good governance.

Public Opinion Surveys:

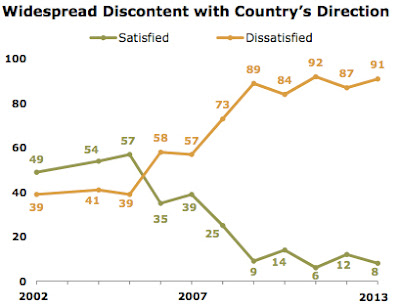

Such an expression of people's will can come in many forms, including results of frequent public opinion polls conducted by multiple professional pollsters in Pakistan and many other countries around the world. One such credible survey is done regularly by Pew Global Research. It shows that the majority of the people believed the country was headed in the right direction in Musharraf years. It also shows that people's satisfaction with Pakistan's direction has been in rapid decline. It has sharply fallen to about 8% in 2013.

Another survey conducted by Gallup Pakistan in August 2013 shows that 59% of Pakistanis have a positive view of President Muaharraf (31% say they hold a favorable opinion of him and another 28% say he was satisfactory). 34% have an unfavorable opinion of the former ruler.

Judiciary and Parliament Approval:

Musharraf's actions of 1999 were legitimized by Pakistan Supreme Court in Syed Zafar Ali Shah v. General Pervez Musharraf, Chief Executive of Pakistan (PLD 2000 SC 869). In addition to endorsing the coup, the Supreme Court granted extensive powers to the new Musharraf Government, empowering it to unilaterally amend the 1973 Constitution and enact new laws without the approval of Parliament.

Musharraf held parliamentary elections in 2002 and subsequently won a parliamentary vote to confirm him as President of Pakistan.

Good Governance Under Musharraf:

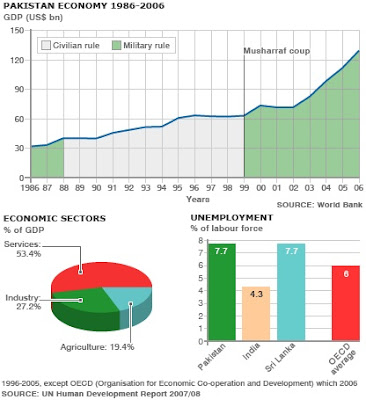

When Musharraf took over in 1999, Pakistan was essentially bankrupt with just a few hundred million dollars in reserves and a heavy debt load which it couldn't repay. Economic growth plummeted to between 3% and 4%, poverty rose to 33%, inflation was in double digits and the foreign debt mounted to nearly the entire GDP of Pakistan as the governments of Benazir Bhutto (PPP) and Nawaz Sharif (PML) played musical chairs. Before Sharif was ousted in 1999, the two parties had presided over a decade of corruption and mismanagement. In 1999 Pakistan’s total public debt as percentage of GDP was the highest in South Asia – 99.3 percent of its GDP and 629 percent of its revenue receipts, compared to Sri Lanka (91.1% & 528.3% respectively in 1998) and India (47.2% & 384.9% respectively in 1998). Internal Debt of Pakistan in 1999 was 45.6 per cent of GDP and 289.1 per cent of its revenue receipts, as compared to Sri Lanka (45.7% and 264.8% respectively in 1998) and India (44.0% and 358.4% respectively in 1998).

So what did Musharraf do to gain the trust of a very large number of Pakistanis who supported his rule after the 1999 coup? He undertook a number of economic and regulatory reforms to rejuvenate the country's economy. Deregulating telecommunications and liberalizing electronic media business, particularly television, immediately brought in significant first wave of domestic and foreign investment and created media and telecom boom in the country. Banking and financial services sector took off and rapidly grew and created lots of jobs. A construction boom followed which more than doubled per capita cement consumption and created millions of new jobs. Exports nearly tripled from about $7 billion in 1999-2000 to $22 billion in 2007-2008, adding millions of more jobs.

Pakistan Savings Rate as Percent of GDP (Source: World Bank) |

Per Capita Cement Consumption in Pakistan Source: Credit Suisse and... |

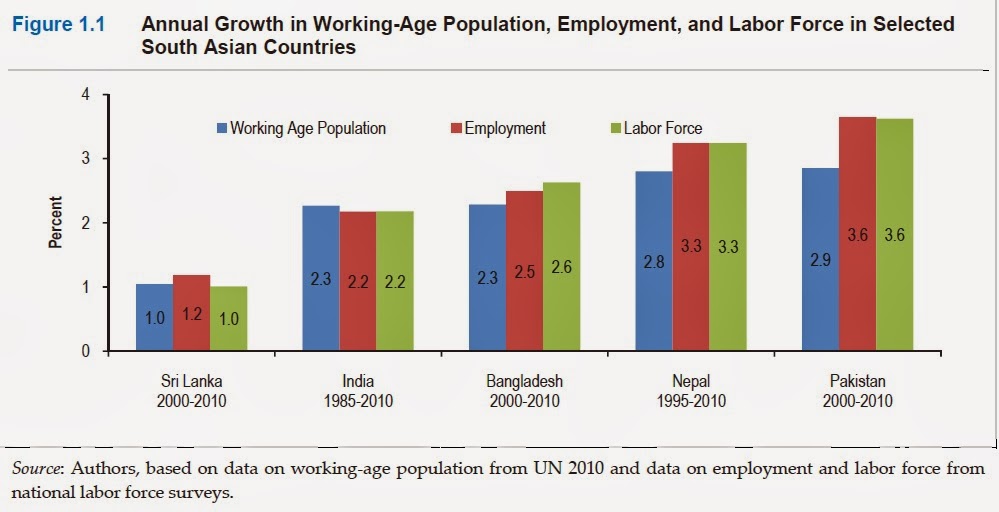

Thanks to the dynamic economy under President Musharraf's rule, Pakistan created more jobs, graduated more people from schools and colleges, built a larger middle class and lifted more people out of poverty as percentage of its population than India in the last decade. And Pakistan has done so in spite of the huge challenges posed by the war in Afghanistan and a very violent insurgency at home.

The above summary is based on volumes of recently released reports and data on job creation, education, middle class size, public hygiene, poverty and hunger over the last decade that offer new surprising insights into the lives of ordinary people in two South Asian countries. It adds to my previous post on this blog titled "India and Pakistan Contrasted in 2010".

The PPP government summed up General Musharraf's accomplishments well when it signed a 2008 Memorandum of Understanding with the International Monetary Fund which said:

"Pakistan's economy witnessed a major economic transformation in the last decade. The country's real GDP increased from $60 billion to $170 billion, with per capita income rising from under $500 to over $1000 during 2000-07". It further acknowledged that "the volume of international trade increased from $20 billion to nearly $60 billion. The improved macroeconomic performance enabled Pakistan to re-enter the international capital markets in the mid-2000s. Large capital inflows financed the current account deficit and contributed to an increase in gross official reserves to $14.3 billion at end-June 2007. Buoyant output growth, low inflation, and the government's social policies contributed to a reduction in poverty and improvement in many social indicators". (see MEFP, November 20, 2008, Para 1)

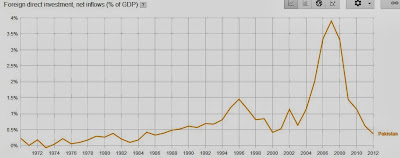

Contrary to what Musharraf bashers dismiss as "aid-fueled " or "consumption-driven" economy in 2002-2007, the economic growth was actually driven by private savings and investments. Private domestic savings rate was over 18% of GDP in Musharraf but has slumped to just 7% in recent years. Pakistan attracted record foreign direct investment (FDI) in telecom, banking, manufacturing and other sectors of the economy. Annual FDI flow into Pakistan reached $5.4 billion in Year 2007-08. As to US aid during and after Musharraf's years in office, it has actually tripled in size from $700 million in 2007-8 to $2.1 billion since 2010. If aid alone were responsible for economic growth, then the GDP growth rate should have accelerated, not plummeted, after Musharraf left office.

In addition to the economic revival, Musharraf focused on social sector as well. Pakistan's HDI grew an average rate of 2.7% per year under President Musharraf from 2000 to 2007, and then its pace slowed to 0.7% per year in 2008 to 2012 under elected politicians, according to the 2013 Human Development Report titled “The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World”.

Overall, Pakistan's human development score rose by 18.9% during Musharraf years and increased just 3.4% under elected leadership since 2008. The news on the human development front got even worse in the last three years, with HDI growth slowing down as low as 0.59% — a paltry average annual increase of under 0.20 per cent.

|

| Rising University Enrollment in Pakistan Starting in 2001-2002. Sou... |

Going further back to the decade of 1990s when the civilian leadership of the country alternated between PML (N) and PPP, the increase in Pakistan's HDI was 9.3% from 1990 to 2000, less than half of the HDI gain of 18.9% on Musharraf's watch from 2000 to 2007.

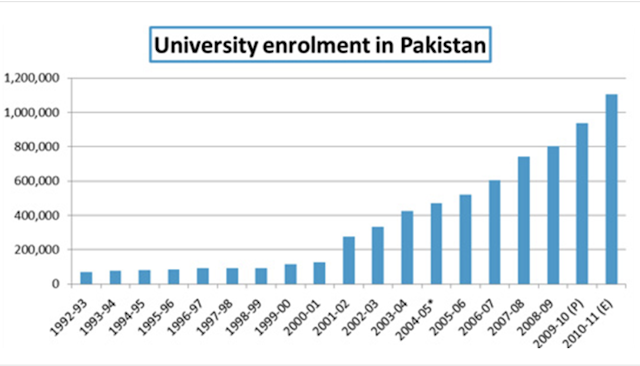

Acceleration of HDI growth during Musharraf years was not an accident. Not only did Musharraf's policies accelerate economic growth, helped create 13 million new jobs, cut poverty in half and halved the country's total debt burden in the period from 2000 to 2007, his government also ensured significant investment and focus on education and health care. The annual budget for higher education increased from only Rs 500 million in 2000 to Rs 28 billion in 2008, to lay the foundations of the development of a strong knowledge economy, according to former education minister Dr. Ata ur Rehman. Student enrollment in universities increased from 270,000 to 900,000 and the number of universities and degree awarding institutions increased from 57 in 2000 to 137 by 2008. In 2011, a Pakistani government commission on education found that public funding for education has been cut from 2.5% of GDP in 2007 to just 1.5% - less than the annual subsidy given to the various PSUs including Pakistan Steel and PIA, both of which continue to sustain huge losses due to patronage-based hiring.

So Why Didn't the Musharraf Miracle Last?

It takes a long time to build and very little time to destroy a beautiful, well-manicured garden with flourishing plants and flowers. A new incompetent, lazy and corrupt gardener can turn it into a disaster by failing to fertilize, water and prune. That's what happened in Pakistan in 2008. A healthy, well-run and growing economy was quickly turned to shambles in a very short time because of policy inaction and neglect. Here's how Pakistani economist Dr. Ashfaque H. Khan explained it in 2010: "What went wrong? Why one of the fastest growing economies in the Asian region until two years ago has been totally forgotten in the region? Firstly, the speed and dimension of exogenous price shocks (oil and food) were of extraordinary proportions. Secondly, the present government found itself totally ill-prepared and clueless in addressing the challenges arising out of the shocks. While rest of the world was taking corrective measures and adjusting to higher food and fuel prices, Pakistan lurched from one crisis to another."

Constitution Not Suicide Pact:

To those who say nothing should trump the constitution of Pakistan, let me remind them that there is legal precedent to suggest that there are things more important than the constitution. "The Constitution is not a suicide pact" is an oft-repeated phrase in American political and legal discourse. It refers to the belief that constitutional restrictions on governmental power must be balanced against the need for survival of the state and its people. It is frequently attributed to Abraham Lincoln who is said to have used it in answering charge that he violated the United States Constitution by suspending habeas corpus during the American Civil War. Others who have used it include Justice Robert H. Jackson (Terminiello v. Chicago, 1949) and Justice Arthur Goldberg (Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, 1963).

Here's a video discussion on the subject:

Civil-military Stand-Off on Musharraf Trial; Musharraf Govt's Perfo... from WBT TV on Vimeo.

Related Links:

Musharraf Wants to Face Trial; Military Opposed to it

Political Patronage Trumps Public Policy in Pakistan

Dr. Ata-ur-Rehman Defends Pakistan's Higher Education Reforms

Twelve Years Since Musharraf's Coup

Pakistan's Economic Performance 2008-2010

Role of Politics in Pakistan Economy

India and Pakistan Compared in 2011

Musharraf's Coup Revived Pakistan's Economy

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on January 26, 2014 at 4:26pm

-

86% of Pakistanis say Musharraf should not be tried alone for his actions of declaring emergency in 2007, according to a nationwide Gallup survey:

Majority Pakistanis (86%) believe individuals privy to and in favor of declaring emergency in the country in 2007 should be tried for treason along with Musharraf. GILANI POLL/GALLUP PAKISTAN

According to a Gilani Research Foundation Survey carried out by Gallup Pakistan, majority Pakistanis (86%) believe individuals privy to and in favor of declaring emergency in the country in 2007 should be tried for treason along with Musharraf.

A nationally representative sample of men and women, from across the four provinces was asked “In your opinion, should individuals who were privy to and in favor of former President Musharraf’s act of declaring emergency in the country in 2007 be tried for treason under Article 6 or do you believe that Musharraf should be tried alone?” Responding to this, 86% were in favor of trying all individuals associated with declaring emergency in 2007 while only 12% think Musharraf should be tried for treason alone. 2% did not respond.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on March 9, 2014 at 10:57am

-

Post-2000, the awkward, inconvenient truth is that, particularly during the regime of retired General Pervez Musharraf and former chief minister Arbab Ghulam Rahim, the physical infrastructure of Tharparkar reached an unprecedented level of progress.

Where, for example, in previous times, only about two kilometres of metalled road was built in a whole year, roads of the same length and more were built every month, and in even less time, for several years.

Grid electricity to main towns, water pipelines to large settlements, preparatory infrastructure for exploitation of coal reserves including work by the post-2008 PPP government, rapid proliferation of telecommunication and mobile phones have vastly enhanced mobility, access and information flow. http://www.dawn.com/news/1091961/tharparkar-a-famine-of-facts

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 9, 2015 at 7:35pm

-

US Civil Rights leader Jesse Jackson to #Pakistan: Let #Musharraf go. You cant move forward while looking backward.

http://tribune.com.pk/story/899678/jesse-jackson-comes-to-musharraf... …

Prominent US politician Jesse Jackson plunged headlong into the murky waters of Pakistani politics on Sunday when he appealed to the authorities to strike the former military ruler’s name off the exit-control list (ECL).

Rev Jackson has also written to US President Barack Obama in this regard.

In an exclusive interview to Express News, Rev Jackson said it was in the interest of Pakistan to let Musharraf leave the country. “I shall visit Pakistan to continue to support Musharraf.”

Jackson has been a longstanding campaigner for human rights and received many international awards. He had also campaigned with US civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr against racism.

In his letter to Obama, the human rights activist has reminded the president that Musharraf had helped the US after 9/11 and that it was now America’s turn to return the favour.

Jackson told Express News that Musharraf was a time-tested ally of the US. He hoped that the Pakistani government would allow the former president to leave the country for receiving medical treatment. He attributed his support for Musharraf to a human rights concern.

“Musharraf has contributed to congenial relations between Pakistan and the US,” said Jackson. “Releasing prisoners always opens up doors of dialogue and we should always prefer reconciliation over confrontation. This way we can finish tension.”

Acknowledging the former president’s international standing, Jackson said it was in the interest of Pakistan to let him go abroad for medical attention. “This will help the prevalent situation move towards improvement.”

Regarding his expectations about the issue, the former US senator said he would appeal directly to the Pakistani government. “I want to visit Pakistan to discuss the matter with the relevant ministers and religious leaders.”

On the subject of US-Pakistan ties, he said: “We have strong relations with Pakistan and they have always been so. We want peace. We want peace between Pakistan and India, within Pakistan and between Pakistan and the US.”

He said the US sees Pakistan as the axis of global peace and security. “We think Pakistan is important for peace in the world.”

Though Jackson has yet to receive a response from Obama, he seeks to insist on getting feedback from the president on his letter. “President Obama wants peace and he also wants justice. We should cooperate for peace and avoid confrontation.”

The former senator hoped that Musharraf would not be harmed and that he would be allowed to leave Pakistan on medical grounds. “We should have the ability to look forward rather than being stuck in the past. We should be able to forgive and move forward.”

Jackson said: “We cannot move forward while looking backward. Nelson Mandela was mistreated in South Africa, but he preferred to foster hope for the future rather than keep remembering the pains of the past.”

The US politician holds a similar point of view. “Following Mandela’s wisdom, hope should be preferred over fear.” (TRANSLATED BY ARSHAD SHAHEEN)

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 9, 2015 at 9:44pm

-

Excerpted from Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition by Nisid Hajari, out now from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Throughout August 1947, as Hindus and Muslims and Sikhs engaged in one of the most terrible slaughters of the 20th century in next-door Punjab province, lights continued to blaze from New Delhi’s ivory-white Imperial Hotel. On weekends, diners packed the tables in the Grill Room overlooking the lawns, while Indian socialites dripping with gold and jewels filled the dance floor well past midnight. To many of the city’s well-to-do, the bloodshed that had erupted upon the birth of modern India and Pakistan still felt unreal. The Indian women in particular seemed to be “on heat,” one British journalist noted hungrily. “The aphrodisiac was independence.”

No band played on Saturday, Sept. 6, however. A curfew had emptied the dining room. Anyone standing on the hotel’s veranda would have been bathed in a different light—a rose-colored glow that filled the horizon to the north. The Muslim neighborhoods of Old Delhi were on fire.

When they imagine the terrible riots that accompanied the 1947 partition of the Indian subcontinent, most people are picturing the bloodshed in the Punjab. On Aug. 15, the new border had split the province in two, leaving millions of Punjabi Hindus and Sikhs in what was now Pakistan, and at least as many Punjabi Muslims in India.

Gangs of killers roamed the border districts, slaughtering minorities or driving them across the frontier. Huge, miles-long caravans of refugees took to the dusty roads in terror. They left grim reminders of their passage—trees stripped of bark, which they peeled off in great chunks to use as fuel; dead and dying bullocks, cattle, and sheep; and thousands upon thousands of corpses lying alongside the road or buried shallowly. Vultures feasted so extravagantly that they could no longer fly.

As awful as the carnage was, though, it was for much of August concentrated in the Punjab. The combatants were mostly peasants, armed with crude weapons. If the two new governments had managed to quell the mayhem quickly, they might in time have found scope to cooperate on issues ranging from economic development to foreign policy. Instead, the infant India and Pakistan would soon be drawn into a rivalry that’s lasted almost 70 years and has cast a nuclear shadow over the subcontinent.

A few short days in Delhi at the beginning of September 1947 helped to tilt the scales. Most train services across the new border had been suspended because of the spiraling massacres, stranding thousands of Muslim civil servants destined for Pakistan in the Indian capital. Desperately short of staff, the Pakistani government was already struggling to cope with hundreds of thousands of traumatized refugees and a stalled economy. Pakistan’s prickly founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, suspected the Indians of deliberately seeking to sabotage his fragile state.

His fears weren’t entirely unfounded. For several days running, according to some eyewitness reports, small groups of Sikh and Hindu militants had been roving the broad, manicured avenues of New Delhi, defying the curfew. Some appear to have been marking out the rooms in government dormitories occupied by Muslim clerks and peons, as well as the houses and bungalows where Muslims lived or worked as servants. A British diplomat later reported seeing a lorry full of Sikhs pull up outside the home of the local chairman of British airline BOAC, which had agreed to transport Muslim officials to Pakistan by air until the trains resumed. “That’s the place,” one of the Sikhs confirmed, carefully noting down the address.

On the night of Sept. 6, sword-wielding gangs began working their way from target to target, dragging out and killing Muslims. The next morning mobs took to the streets all over the city. One descended on the military airfield at Palam, from where the BOAC charters were taking off; another blocked the runways at the civilian Willingdon Airfield as airline employees fled in terror. Muslims caught out in the open were stabbed and gutted, including five who were killed in front of New Delhi’s cathedral while worshippers celebrated Sunday Mass. Looters broke into Muslim shops in Connaught Place, the colonnaded arcade at the heart of the city. By 10 that night, Delhi hospitals were reporting three times as many Muslim as non-Muslim casualties.

Rushing to Connaught Place, India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, was appalled to see a contingent of police standing by idly as Hindu and Sikh rioters carried off ladies’ handbags, cosmetics, and wool scarves—even bottles of fountain-pen ink. Nehru grabbed a baton from one indifferent policeman and flailed away at the crowd himself. The prime minister would learn later that Delhi police had picked up rumors that “two well-known [Sikh] extremists from Amritsar” had organized refugees from the Punjab into makeshift killing squads. Plot or no, Delhi’s police appeared content to let the rioters go about their business unmolested.

Although they later tried to play down the extent of the chaos, Nehru and his deputy, the tough Home Minister Vallabhbhai Patel (known as “Sardar,” or Chief), at least temporarily lost control of their own capital. Ministries sat empty because clerks and officials were too afraid to come to work. Buses, taxis, and horse-drawn tongas—usually driven by Muslims—stopped plying the roads. The phones went dead. Within 48 hours, hospital mortuaries had filled to capacity; dozens of bodies lay unclaimed on the streets for days. With food shipments rotting in abandoned trains, ration shops closed up. At one point the city had only two days’ stock of wheat in reserve.

Lord Louis Mountbatten, Britain’s last viceroy, had stayed on after independence to serve as India’s first governor-general. Many of his staff members had seen combat with him during World War II; even they were stunned by the whirlwind. “This is more hectic than at any time of the war,” Mountbatten’s chief of staff Lord Hastings Ismay wrote to his wife—a potent statement from a man who had lived through the Blitz. He advised her to cancel her plans to come out to see him: “There is a possibility—and most keen a possibility—that orderly Government may collapse.”

Initially none of the Indian leaders doubted that Sikhs, who had played a central role in the Punjab violence, had spearheaded the Delhi attacks, too. More than 200,000 non-Muslim refugees from the Punjab had squeezed into the capital, and plenty of them thirsted for revenge. Patel called in local Sikh leaders and threatened to toss their followers into concentration camps if the violence did not cease. He also gave the army a “free hand” to go after Sikh troublemakers. Commanders ordered their troops to shoot rioters on sight. Though the military could not admit openly to targeting any particular community, Mountbatten joked grimly, “the object would have been achieved if in 48 hours’ time the local graves and concentration camps were occupied more fully by men with long beards than those without.”

Very quickly, however, Patel’s assessment of the threat changed. The problem was not just the Sikhs. Earlier police reports had also warned of a brewing Muslim uprising in the capital. Most of the city’s ammunition dealers were Muslim, as were most of its blacksmiths. The latter had supposedly converted their workshops to churn out bombs, mortars, and bullets. Patel had been worried enough about the threat to issue licenses to several new Hindu arms dealers in Delhi. He had “been giving arms liberally to non-Muslim applicants” for self-defense, he reassured a colleague.

Some Delhi Muslims were indeed armed. They fought back against the police as well as the Hindu and Sikh gangs; among reported gunshot victims on Sunday, non-Muslims actually outnumbered Muslims 45 to 20. Though evidence of any conspiracy is scant, quite a few Delhiites seemed to believe that the city’s Muslims posed as great a threat as the death squads, if not greater.

http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/history/2015/06/how...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on June 9, 2015 at 9:47pm

-

Excerpted from Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition by Nisid Hajari, out now from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

During the riots, officials trying to rescue Muslims often found the public reluctant to help. Owners of private cars and trucks removed key parts so that the authorities couldn’t requisition the vehicles. Volunteer drivers pretended to get lost or to develop engine trouble when asked to deliver aid to Muslim areas. (Eventually the government enlisted idealistic students to ride along and watch over them.) Even four days into the rioting, the U.S. military attaché witnessed Indian army troops standing by as Muslim women and children were clubbed to death at Delhi’s railway station.

Indian nationalist leader Jawaharlal Nehr asks members of the Constituent Assembly to take a pledge of loyalty to the new state in August 1947.

Indian nationalist leader Jawaharlal Nehr asks members of the Constituent Assembly to take a pledge of loyalty to the new state in August 1947.

Photo by Keystone/Getty Images

Patel was more in tune with the popular mood than Nehru. While the principle that Hindus and Muslims should be able to live together remained central to Nehru’s vision for India, the Sardar was less sentimental. He did not trust that all of India’s Muslims, many of whom had until recently supported Jinnah, had switched loyalties. If they did not think of themselves as Indians, he believed, then they belonged in Pakistan.

Nehru would almost certainly have lost an open fight with his deputy. Horrified by the casualty reports, the prime minister tried to ban Sikhs from wearing their ceremonial knives, known as kirpans. Patel pushed back, saying the decree discriminated against the Sikh faith. “Murder is not to be justified in the name of religion,” Nehru protested. Yet after a “violent disagreement” between the two men, the Sardar triumphed. Sikhs regained the right to carry their daggers after a 48-hour pause.

Nehru seemed to believe he had a better chance of quelling the unrest single-handedly than by working through his own administration. He went “on the prowl whenever he could escape from the [Cabinet] table, and took appalling personal risks,” Ismay recalled. Nehru would angrily face down mobs himself, rushing from trouble spot to trouble spot. A veritable tent city, filled with Muslim refugees, sprouted on the lawns of his York Road bungalow.

One night a Muslim friend named Badruddin Tyabji showed up at Nehru’s door to alert him to an especially troubled area—the Minto Bridge, which Muslims fleeing their Old Delhi neighborhoods had to cross to reach the safety of refugee camps in New Delhi. Each night, Tyabji said, gangs of Sikhs and Hindus lurked nearby and sprung upon the defenseless Muslims as they trudged past.

Nehru immediately bolted from his seat and dashed upstairs. He returned a few minutes later holding a dusty, ungainly revolver. The gun had once belonged to his father, Motilal, and hadn’t been fired in years. He had a plan, he told Tyabji. They would don soiled and torn kurtas and drive up to Minto Bridge themselves that night. Disguised as refugees, they’d cross the bridge, and when the thugs tried to waylay them, “We would shoot them down!” The stunned Tyabji was able to persuade the leader of the world’s second-biggest nation “only with great difficulty” that “some less hazardous and more effective method for putting an end to this kind of crime should not be too difficult to devise.” Mountbatten feared Nehru’s impulsiveness would get him killed and assigned soldiers to watch over him.

Nehru’s individual heroics evoked great admiration in men like Ismay and Mountbatten. But they did little for Delhi’s Muslims. After the initial wave of attacks, thousands had fled their homes. Authorities almost immediately started evacuating the rest, claiming they could not guarantee the safety of residents if they remained where they were.

Muslims were dumped in guarded sites by the truckload—places which it would be generous to describe as refugee camps. Within a week, more than 50,000 were crammed into the Purana Qila, a ruined fort. They huddled pitifully on the muddy ground with no lights, no latrines, and hardly any water or food. The Pakistan government flew in shipments of cooked rice and chapatis all the way from Lahore to feed them.

Ismay melodramatically compared the scene at the Purana Qila to “Belsen—without the gas chambers.” Dignified Muslim professors and lawyers were squashed next to cooks and mechanics, longtime Gandhians next to stranded, would-be Pakistan bureaucrats. Wounded and sick moaned without medical attention; babies were born in the open. Armed Sikhs patrolled the one choked entrance, taking down the license plate numbers of Europeans driving in to deliver food and supplies to their friends and former servants.

With the help of Gurkha and South Indian troops—who were less vulnerable to the sectarian passions roiling their northern counterparts—authorities managed to control the worst of the violence within a week. Volunteers began to clean up the streets, and ration shops reopened. Nehru asked the governors of other Indian provinces to take in tens of thousands of Punjab refugees, to get them out of the capital.

But the riots fatally undermined any trust Pakistani leaders may have had in their Indian counterparts. Nehru’s estimate that 1,000 victims had died in the rioting was generally considered “ridiculous,” according to U.S. Ambassador Henry Grady. He figured the true toll to be at least five times higher; others said 20 times.

At the height of the violence, Jinnah was inundated with hysterical reports from the Pakistani ambassador in Delhi, Zakir Hussain. Hundreds of Muslim refugees had carpeted the grounds of his house, Hussain reported, and the embassy’s food supplies were running out. He described the Indian government as either intent upon eliminating the capital’s Muslim population or indifferent to their fate. Army troops were openly gunning down innocent Muslims. In one particularly florid cable Hussain warned, “The entire Muslim population of India is facing total extermination.”

A conviction was taking hold among Jinnah and his lieutenants that India had launched an “undeclared war” on the weaker Pakistan. The Indian leaders seemed incapable of transferring Pakistan government servants to the new capital Karachi, or of protecting them in their Delhi homes. Cargo trains full of equipment and supplies meant for Pakistan were being derailed and torched in the Punjab. At least some members of the Indian Cabinet appeared to be winking at the Sikhs’ murderous activities. “It is obvious that their orders are not carried out,” one of Hussain’s cables said of the Indian leaders, “or at least different members of the government are following conflicting policies.”

In mid-September, Ismay spent three days in Karachi trying to convince Jinnah that the Indian government bore Pakistan nothing but goodwill. Jinnah was dismissive. He was convinced that Sikh and Hindu militia leaders had planned the violence in the Punjab as well as Delhi. Though intelligence had given some inkling of their plans over the summer, they had been allowed to walk free. With its vast resources and powerful military, Jinnah believed, India could even now have suppressed the Sikhs if only Nehru had had the necessary “will and guts.” Instead he could not even guarantee the safety of Muslims in his own capital.

Ismay returned to Delhi profoundly depressed. In a secret codicil to his report, meant for Mountbatten’s eyes only, he warned that Jinnah had begun speaking in dangerously warlike tones. In the very first hour of their talks the Pakistani leader had struck Ismay “as a man who had given up all hope of further cooperation with the Government of India.” All that had happened in the month since independence just “went to prove that they were determined to strangle Pakistan at birth,” Jinnah had told Ismay grimly. “There is nothing for it but to fight it out.”

http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/history/2015/06/how...

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on April 24, 2016 at 12:57pm

-

"Speaking fee for #Musharraf in $150K-200K range for a day," says Embark USA President David B. Wheeler. #Pakistan

http://www.newsweek.com/pakistans-musharraf-lucrative-speaking-fees...

"The [speaking] fee for Musharraf would be in the $150,000-200,000 range for a day," says Embark President David B. Wheeler, "plus jet and other V.I.P. arrangements on the ground." Wheeler says Clinton, for whom Embark has arranged speaking engagements in the Middle East, commands up to $250,000 per appearance. "If we did multiple events in multiple cities, [Musharraf] could get closer to the $500,000 to $1,000,000 range [for a series of talks]," he said. Embark, which promises "unique experiences that educate, entertain and enlighten," has also booked speeches for former U.S. President George H.W. Bush and former U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell.

Pakistanis who know Musharraf well say this is good news for the former president, who is not believed to have salted away a fortune as some of his predecessors have done (Musharraf will only receive a modest army retirement pension). But he is a long way from the poor house. Workers are putting the finishing touches on a mansion, said to be worth some $2 million dollars, that he is building on five acres of prime land just outside Islamabad. Since his resignation he has been playing golf and tennis with friends, surrounded by heavy security, and is also planning to write a sequel to his successful 2006 autobiography, "In the Line of Fire," which could easily net him another seven-figure windfall.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 20, 2020 at 8:29am

-

Cunningham, Edward, Tony Saich, and Jessie Turiel. 2020. Understanding CCP Resilience: Surveying Chinese Public Opinion Through Time. Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation.

https://ash.harvard.edu/publications/understanding-ccp-resilience-s...

This policy brief reviews the findings of the longest-running independent effort to track Chinese citizen satisfaction of government performance. China today is the world’s second largest economy and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has ruled for some seventy years. Yet long-term, publicly-available, and nationally-representative surveys in mainland China are so rare that it is difficult to know how ordinary Chinese citizens feel about their government.

We find that first, since the start of the survey in 2003, Chinese citizen satisfaction with government has increased virtually across the board. From the impact of broad national policies to the conduct of local town officials, Chinese citizens rate the government as more capable and effective than ever before.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on August 20, 2020 at 8:30am

-

Harvard Study: The study found satisfaction with the government improved overall from 2003 to 2016.

According to the study, the proportion of respondents satisfied with the central government rose from 86.1 per cent in 2003 to 93.1 per cent in 2016, although it dipped to 80.5 per cent in 2005.

https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3093983/chinese-ra...

“From the impact of broad national policies to the conduct of local town officials, Chinese citizens rate the government as more capable and effective than ever before,” authors Edward Cunningham, Tony Saich and Jessie Turiel, from the Roy and Lila Ash Centre for Democratic Governance and Innovation, wrote in the report.

Their study was based on data from eight separate surveys, including face-to-face interviews, conducted between 2003 and 2016. It involved more than 31,000 Chinese in both urban and rural areas. The surveys were designed by the Ash Centre at the Harvard Kennedy School, and carried out by a “reputable domestic Chinese polling firm”, the report said, without elaborating.

They rejected a theory that Beijing was sitting on a “social volcano” of suppressed public dissatisfaction, but cautioned that without robust economic growth – and if austerity measures were introduced – the widespread approval might change.

-

Comment by Riaz Haq on December 24, 2020 at 1:12pm

-

The Greater Thal Canal project was inaugurated by former president Gen (retd) Pervez Musharraf on August 16, 2001, at Noorpur Thal, adjacent to Adi Kot Chashma Jhelum Link Canal. The estimated cost of the project was around Rs30 billion.

https://tribune.com.pk/story/2134724/greater-thal-canal-willfully-i...

The project was to be completed in eight years, and after completion, it was expected that almost Rs1.73 million acres of land would be irrigated in Bhakkar, Layyah, Khushab and Jhang districts. Apart from this, approximately 1.97 million acres of arid land would be converted into fertile land. So far, the first phase of the project has been completed with the cost of Rs10 billion.

The project was conceived in 1836 when Queen Victoria ordered a survey of the area. The survey was completed in six months. However, the project could not be initiated due to the opposition of the Hindus who alleged the British of giving undue favours to the Muslims living in the area.

ADB TO PROVIDE PAKISTAN $1.055B FOR NINE PROJECTS

Former military ruler General Ziaul Haq also made an unsuccessful attempt to initiate this project in 1979.

Although, the construction of phase I has affected farmers' fertile land

After Musharraf's regime, the democratic governments shelved the project which could have brought an agricultural revolution in the country. The network of canals has vanished under the mounds of sand. The canal escape of the project has also turned into a forest of shrubs and wild bushes.

The government has allocated a fund of Rs250 million for the cleaning of the canal. Reportedly, the phase II and III comprise of Dhingana Branch, Mankera Branch and Noorpur Thal Branch which have been ignored for the last 19 years.

The completion of phase II and III would irrigate millions of acres of land in the area of Thal, Bhakkar, Jhang, Khushab and Layyah and change the fate of poor farmers.

Comment

Twitter Feed

Live Traffic Feed

Sponsored Links

South Asia Investor Review

Investor Information Blog

Haq's Musings

Riaz Haq's Current Affairs Blog

Please Bookmark This Page!

Blog Posts

Modi's AI Spectacle: Chaos and Deception in New Delhi

The India AI Impact Summit 2026, held at Bharat Mandapam in New Delhi, has been marred by chaos, confusion and deception. The events on the ground have produced unintended media headlines for India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi who wants to be seen as the "vishwaguru" (teacher of the world) in the field of artificial intelligence as well. First, there was massive chaos on the opening day, with long…

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on February 19, 2026 at 12:00pm — 11 Comments

India-Pakistan Cricket Match: The Biggest Single Event in the World of Sports

Why did Pakistan's decision to boycott the India-Pakistan match in solidarity with Bangladesh in this year's T20 World Cup send shockwaves around the world? And why did it trigger the International Cricket Council's and other cricket boards' urgent efforts to persuade Pakistan to return to the match? The reason has a lot to do with its massive financial impact, estimated to be as much as …

ContinuePosted by Riaz Haq on February 11, 2026 at 4:00pm — 2 Comments

© 2026 Created by Riaz Haq.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network to add comments!

Join PakAlumni Worldwide: The Global Social Network